The Null Device

2013/4/9

A day after the death of an elderly, long-retired Margaret Thatcher, the reactions in Britain have been varied. The national news media have generally been lavish in their hagiography, at most conceding that Thatcher “polarised opinion” or was “controversial”; the implication being that all sides, from the yuppies whom made out like bandits during the Big Bang to the miners who were kicked in the teeth, had, over time, put their differences aside. (The BBC has been particularly fawning, careful to avoid giving a voice to anyone who may say anything remotely critical, or in any way shatter the illusion that the PM who smashed the miners' unions, immiserated the North and began the dismantling of the post-WW2 social contract may well have been a much loved and thoroughly apolitical member of the Royal Family. Between that and their silence on the privatisation of the NHS, one suspects that they are betting that, maybe if they cooperate enthusiastically, the Tories won't dismember them and sell the bits off to Rupert Murdoch before the next election.) Even the Guardian, whilst publishing a mildly condemnatory editorial, hedged its bets, as not to offend those of its readers who vote Conservative (and presumably there are some). Regional newspapers have been somewhat less equivocal, especially those in places like Sheffield, Newcastle and Wales. Meanwhile, television schedules have been cleared to make room for turgid memorial programming.

Last night, after her death was announced, spontaneous celebrations did erupt in parts of Britain; as of yesterday afternoon, the centre of Liverpool reportedly looked “like bonfire night on Endor”, and other celebrations took place in Glasgow, Bristol, Brixton and Republican areas of Northern Ireland. Elsewhere, the manager of an Oddbins was suspended after announcing a special on champagne “in case anyone wanted to celebrate for any reason”.

Other than that, there have been few signs of public jubilation in London; no red bunting bedecking streets, no spontaneous street parties around portable stereos blaring out Billy Bragg songs, no jubilant signs in windows, not even an uncanny sense of euphoria in the air. And, when one thinks about it, it's hardly surprising, as there's precious little to celebrate. An old, frail woman, whose actions caused considerable suffering for many (and, for a few, great fortune) a quarter-century ago, died at an advanced age, amidst luxury; and, short of being borne to Valhalla on the wings of valkyries, there could scarcely be a more victorious way to exit life. If she was aware of anything in her last days, it would have been of the triumph of her views and the utter vanquishment of all opposition. The welfare state has been dismantled to an extent she dared not imagine, trade unions are all but extinct, and neo-Thatcherism is the backbone of all admissible political parties. Other than there still being homosexuals and trains in Britain, there could have been little to disappoint her. Thatcher may be dead, but Thatcherism is stronger than ever. If anyone has reason to be popping the corks on those bottles of champagne, it would be the Conservative Party faithful and perhaps the Blairite wing of Labour, paying tribute to the end of a triumphant life.

While she may have been victorious, that is not to say that her victory was accepted. Perhaps telling are official shows of respect which were not called for, in case lack of observance says too much. For instance, football matches will not be observing a minute's silence. There will also be no state funeral, which would have required both a parliamentary vote (and the spectacle of Labour backbenchers defying the whip and Sinn Fein members being ejected from the chamber would have been somewhat insalubrious) and a national minute's silence. The funeral itself will be one step short of a state funeral, and the first Prime Minister's funeral attended by the Queen since Churchill's state funeral; it will be held next Wednesday, with central London under lockdown and a heavy police presence; one imagines that Thatcher wouldn't have wanted it any other way.

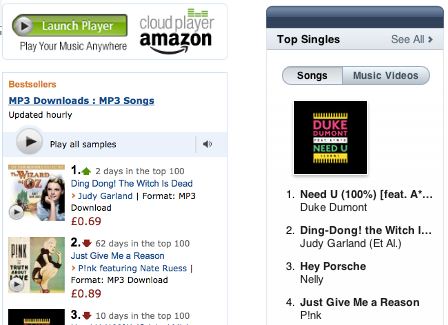

Finally, at the time of writing, Judy Garland is enjoying an uncanny career resurgence in the British pop charts; Ding Dong The Witch Is Dead is at number 2 on the iTunes chart and number 1 on the Amazon MP3 chart. Yay for slacktivism!

Continuing the Margaret Thatcher Memorial Season on this blog: why the Left gets neoliberalism wrong, by political scientist Corey Robin. It turns out that the thing about rugged individualism is (once one gets beyond the pulp novels of Ayn Rand and Robert Heinlein, not exactly founts of academic rigour) a red herring, and the true atom of the neoliberal world view is traditional, vaguely feudal, hierarchical structures of authority: patriarchial families, and enterprises with owners and chains of fealty:

For all their individualist bluster, libertarians—particularly those market-oriented libertarians who are rightly viewed as the leading theoreticians of neoliberalism—often make the same claim. When these libertarians look out at society, they don’t always see isolated or autonomous individuals; they’re just as likely to see private hierarchies like the family or the workplace, where a father governs his family and an owner his employees. And that, I suspect (though further research is certainly necessary), is what they think of and like about society: that it’s an archipelago of private governments.

What often gets lost in these debates is what I think is the real, or at least a main, thrust of neoliberalism, according to some of its most interesting and important theoreticians (and its actual practice): not to liberate the individual or to deregulate the marketplace, but to shift power from government (or at least those sectors of government like the legislature that make some claim to or pretense of democratic legitimacy; at a later point I plan to talk about Hayek’s brief on behalf of an unelected, unaccountable judiciary, which bears all the trappings of medieval judges applying the common law, similar to the “belated feudalism” of the 19th century American state, so brilliantly analyzed by Karen Orren here) to the private authority of fathers and owners.By this analysis, while neoliberalism may wield the rhetoric of atomised individualism, it is more like a counter-enlightenment of sorts. If civilisation was the process of climbing up from the Hobbesian state of nature, where life is nasty, brutish and short, and establishing structures (such as states, legal systems, and shared infrastructure) that damp some of the wild swings of fortune, neoliberalism would be an attempt to roll back the last few steps of this, the ones that usurped the rightful power of hierarchical structures (be they noble families, private enterprises or churches), spread bits of it to the unworthy serfs, and called that “democracy”.

On a related note, a piece from Lars Trägårdh (a Swedish historian and advisor to Sweden's centre-right—i.e., slightly left of New Labour—government) arguing that an interventionist state is not the opposite of individual freedom but an essential precondition for it:

The linchpin of the Swedish model is an alliance between the state and the individual that contrasts sharply with Anglo-Saxon suspicion of the state and preference for family- and civil society-based solutions to welfare. In Sweden, a high-trust society, the state is viewed more as friend than foe. Indeed, it is welcomed as a liberator from traditional, unequal forms of community, including the family, charities and churches.

At the heart of this social compact lies what I like to call a Swedish theory of love: authentic human relationships are possible only between autonomous and equal individuals. This is, of course, shocking news to many non-Swedes, who believe that interdependency is the very stuff of love.

Be that as it may; in Sweden this ethos informs society as a whole. Despite its traditional image as a collectivist social democracy, comparative data from the World Values Survey suggests that Sweden is the most individualistic society in the world. Individual taxation of spouses has promoted female labour participation; universal daycare makes it possible for all parents – read women – to work; student loans are offered to everyone without means-testing; a strong emphasis on children's rights have given children a more independent status; the elderly do not depend on the goodwill of children.So, by this token, Scandinavian “socialism” would seem to be the most advanced implementation of individual autonomy and human potential yet achieved in the history of civilisation whereas Anglocapitalism, with its ethos of “creative destruction”, is a vaguely Downtonian throwback to feudalism.