The Null Device

Posts matching tags 'kraftwerk'

2015/1/22

I am writing this on a train to London from Birmingham, where I have spent the past two days at an academic conference about the electronic music group Kraftwerk. There were some 175 people in attendance; their ages varied from those who had not yet been born during Kraftwerk's heyday to a sizeable contingent of (mostly) men of a certain age who had been at various legendary shows back in the early 80s. The conference, whilst theoretically an academic conference, was open to the general public, and the talks presented varied from critical-theoretical analyses of the signifiers in various records to autobiographical monologues.

The conference began with Stephen Mallinder, of Cabaret Voltaire, talking autobiographically about his own experience of Kraftwerk and how they inspired his and his bandmates' own music-making; he mentioned that, back in the 1970s, he and his mates would refer to traffic cones as “kraftwerks”. Later, Nick Stevenson talked specifically about Cabaret Voltaire, the Sheffield scene, their use of Dadaist techniques and Burroughs' cut-up technique, and the themes of “the control culture” in their music. Other than that, the rest of of the first day was occupied with going through Kraftwerk's early career and first few albums, as well as the “archaeological period” of the three pre-Autobahn albums one gets the impression Ralf Hütter would rather were struck from the historical record. David Stubbs, author of the recent Krautrock book Future Days, talked about this period, tracing the band's history from their shambolic start as The Organisation (which, in surviving footage of live performances, looks like an “on-the-nose parody of Krautrock” in all its scruffy, hippie shambolicness), through the first three albums—Kraftwerk 1 (whose pastoral sound prefigured what Boards Of Canada would do several decades later), Kraftwerk 2 (where the potential of drum machines first appeared) and Ralf & Florian (which, in its title and cover photograph, showed the artists starting to make themselves part of the artwork, perhaps echoing Gilbert & George, who had visited Düsseldorf in that period). This was followed by a talk by David Pattie, a Glaswegian academic, elaborating on Ralf & Florian and from that, the question of Kraftwerk's relationship with Germanness. Among other things, Pattie pointed out a progression in the works of Kraftwerk and other West German bands (Can, Popol Vuh, Tangerine Dream, Neu! and Kluster/Cluster) through the early 70s; a divergence from pure rhythm and/or noise and rediscovery of melody in subsequent albums, and put forward the theory that all these bands had initially set out to reject the musical heritage of their forefathers, and gradually come to an accommodation with it.

In the afternoon, Melanie Schiller (from Düsseldorf, via Groningen) examined Autobahn and its cover artwork, examining the use of space in the sound and the past, present and future as depicted in the LP artwork, and the sense of forward motion, and of there being a start (the sound of the key in the ignition) but not an end (the road going on forever ahead; the self-referential lyrics referring to turning the radio on and hearing the song on it, forming a loop), and, of course, the Beach Boys reference alluding to the American car-song trope. This was followed by a talk by Hillegonda Rietveld about the Trans-Europa Express album; its theme of a borderless, unified Europe, the echoes of an elegant/decadent pre-war past (Neonlicht has a vaguely Weimar feel to it), and its musical antecedents (such as Pierre Schaeffer's 1948 Musique Concréte sound-poem etude aux chemins de fer, and parallels with railway rhythms in the blues in America). The final talk of the day, by Uwe Schütte, about Die Mensch-Maschine, and the idea of the Man-Machine, was rich with details and connections; he tied in Soviet structuralism (the cover artwork drew heavily on El Lissitzky's compositions), a notorious (though in today's climate, quaintly tame) 18th-century atheist pamphlet titled L'Homme-Machine, musical automata throughout the ages, a French novelty act named Les Robots Music, E.T. Hoffmann's 1817 Romantic novel Der Sandmann, Karel Čapek's Rossum's Universal Robots, Fritz Lang's Metropolis, and the evolution of Kraftwerk's own stage robots. After this, former Kraftwerk member Wolfgang Flür was to read from his memoir, I Was A Robot, but was somehow unable to make it; in his stead, Rüdiger Esch (formerly of electro-industrial band Die Krupps) spoke about his book Electri_City, about the history of the Düsseldorf music scene.

The second day of the conference had a few more interesting talks; Pertti Grönholm spoke about the nostalgic retrofuturism in the music of Kraftwerk, specifically singling out the Autobahn B-side Morgenspaziergang, a short pastoral tone-poem of sorts, and Radioland, with its nostalgia for childhood radio listening. Ulrich Adelt (an academic from Hamburg based in Wyoming) talked about Amon Düül II and their unsuccessful Made In Germany novelty record, Faust (who played with the whole idea of authenticity by projecting footage of their guitarist playing a solo while he stood still), the leftist squatter blues-rock/proto-punk band Ton Steine Scherben (who never made much of an impact outside of the German-speaking world) and the Kosmische Musik movement and their prefiguration of what would later devolve into the New Age genre, finally finishing by boldly attempting to reclaim Giorgio Moroder and Donna Summer for the Krautrock genre. This led into a monologue from Rusty Egan, former Blitz Club DJ and drummer from new-romantic synthpop band Visage, Camden nightclub proprietor and currently still a working music producer and DJ. Egan was not so much an academic speaker as a force of nature; attired in jeans, turtleneck and leather jacker, all black, his hair slicked back, he went on for over an hour, pacing the stage, showing photographs on his laptop, playing fragments of tracks he had worked on recently, and telling anecdote after anecdote, often framed with sound effects, funny voices, hand gestures and beatboxing. One gets the feeling he could easily have gone on for another few hours, had it not been time to adjourn for lunch.

After the break, there were three more talks: Heinrich Deisl (who edits an Austrian music magazine titled Skug, which is a little like The Wire, only in German) talked about the metaphors of the Autobahn and the German forest in the music of Kraftwerk, Wolfgang Voigt and the Detroit techno project Dopplereffekt (who, like most Detroit techno artists, are African-American, but affect a stylised Germanness in their art; one of their albums is titled Gesamtkunstwerk). Alexei Monroe spoke about Laibach, their own relationship to modernism and problematic history, and their engagement with dystopian ideology. Finally, Alexander Harden talked about the topic of post-human authenticity, and the question of how one can ascribe authenticity (or its absence) to an act like Kraftwerk.

One theme that kept emerging in the talks was that of Kraftwerk's (and, to a lesser extent, other bands') relationship to the idea of Germany and Germanness, and the country's problematic history. In the late 60s and early 70s, the trauma and shame of the Third Reich and World War 2 was still relatively recent; most night porters in Düsseldorf hotels (as Rusty Egan mentioned) had missing limbs, the British music press made crude Nazi references when faced with the idea of there being bands from Germany, and the youth of the nation were waking up to the idea of post-war denazification having been largely unsuccessful, and of people in positions of power having done terrible things. The idea of Germany was contaminated by Nazism, and so was a lot of its much-vaunted culture, to which music had been central. There was the very real idea of Stunde Null, hour zero, of there being nothing before 1945 worth salvaging; and, indeed, a lot of the Krautrock bands started partly with this assumption, rejecting both the Western classical canon and the Anglo-American blues/rock-based sounds that were filling the airwaves, and venturing outward, to the extremes of experimental noise, the “ethnographic forgeries” of Can, to heavy psychedelic experimentation or the sounds of an imagined Cosmos. But, of course, that is not sustainable forever; and even if one does keep it up, one only has to venture abroad to be put in one's place as one of the Krauts.

Kraftwerk's work, at least from Autobahn (their own Stunde Null) onwards, attempts to answer the question of what is to be done with the past. For all its futurism, it is deeply nostalgic, albeit for the forward-looking pulse of modernism, the future that never was; in part for the Bauhaus-era modernism that was so brutally cut off (as evident in the video for Trans-Europa Express, with its 1930-vintage turbine train model zooming past Metropolis-style buildings), though partly also for the 1950s Wirtschaftswunder years of their own childhoods. What is to be done with the terrible years in between? Well, as much as in one sense, Kraftwerk strive to close the gap, their works are peppered with references which German audiences can pick up, alluding to the unspoken time before Stunde Null: the radio on the cover of Radioactivity, for example, resembles those distributed by the Nazi authorities to households, and indeed, the Autobahn system itself was bound up with the Third Reich (who did not initiate the programme though greatly extended it). As for audiences abroad, rather than seeking to escape German stereotypes, Kraftwerk took them and played, mischievously, to them; becoming the stiff, deadpan robot-men, and throwing in the occasional ambiguous turn of phrase like “total music” or the “mother language”, as if to see if they can jar the foreigners into Mentioning The War again. But Kraftwerk have, discreetly, the last laugh.

Kraftwerk's significance in popular music is hard to overestimate; on their shoulders stand not only electronic pop music (from the early synthpop bands of the late 70s to today's commercial hits), house, techno and dance music, but also much of hip-hop, via Afrika Bambaataa. As Heinrich Diesl quoted, “Before Kraftwerk, German pop music was perceived as Schlager; afterward, it was perceived as Techno”. And, because of their position at the intersection of various historical currents, there is enough to discuss about them to fill an academic conference. Speaking of which, the organiser, Dr. Uwe Schütte, says that, if all goes well, there should be an academic conference about Krautrock at Aston University in a year or two.

2013/11/5

I am back in Reykjavík, Iceland; this time, I came here on occasion of Kraftwerk playing a gig at the Harpa concert hall. Having missed out on tickets to see them in New York (when they played tantalisingly close to the Chickfactor 20th anniversary gigs) and London and also having enjoyed visiting Iceland before, when the Reykjavík gig was announced, I jumped at the opportunity.

Harpa is the new concert hall built recently in Reykjavík; it was part of a grand project started at the height of Iceland's finance bubble; when the economic crisis hit, construction was suspended, but then the government decided to finance the concert hall, which ended up opening in 2011. It is a spectacular-looking building, and a great place to see concerts in.

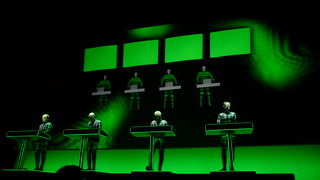

On the way into the hall, we were handed a pair of 3D glasses each; these were not the red/blue ones, but some other type, with sheets of slightly tinted transparent plastic (possibly polarising filters?). Soon, a vocoded/synthesised voice announced “Damen und Herren, Ladies and Gentlemen...”, and the curtain fell slowly to the ground revealing the four members (Ralf and the three “new” guys, who've only been in the band for some 20 years), in grid-patterned body suits, standing in position behind black consoles whose edges were lit like vector graphics; behind them, a screen showed video projections. They started the first song: “The Robots”; the consoles' vector edges glowed red, and the screen was filled with Kraftwerk's computer-rendered doppelgängers, moving robotically, their extending arms projecting out of the screen. Then they went into “Metropolis”, with the consoles highlighted in white, and the screen filled with a geometric, monochromatic metropolis, a city of high buildings through which the camera glided, like a Bauhaus/Le Corbusier ideal of modernity.

The rest of the set followed, with the visuals working spectacularly well; undulating three-dimensional sheets of green pixelised digits (Numbers), the vaguely Russian Constructivist-inspired 3D forms in The Man-Machine, Volkswagens and 1970s-vintage Mercedes motoring through green landscapes in a somewhat abbreviated Autobahn (the video of which seemed to be set in the era when it was written; other than the cars on the roads, these days, a road trip through Germany without seeing a single wind turbine would be unlikely), text and graphics floating above Tour de France footage, 3D-rendered musical notes gliding from the screen into the faces of the audience and more.

Several songs (like The Model/Das Modell, Neon Lights/Neonlicht and Die Mensch-Maschine) were performed with both English and German verses. Some of the songs were updated for today; Radioactivity mentioned Fukushima, and the Spacelab video zoomed in on Iceland, to applause from the audience, before ending with a flying saucer landing somewhere near Düsseldorf. Computer World had a particular resonance in the wake of recent events, but has not, to date, been rewritten to mention the NSA.

The rest of the set followed, with the visuals working spectacularly well; undulating three-dimensional sheets of green pixelised digits (Numbers), the vaguely Russian Constructivist-inspired 3D forms in The Man-Machine, Volkswagens and 1970s-vintage Mercedes motoring through green landscapes in a somewhat abbreviated Autobahn (the video of which seemed to be set in the era when it was written; other than the cars on the roads, these days, a road trip through Germany without seeing a single wind turbine would be unlikely), text and graphics floating above Tour de France footage, 3D-rendered musical notes gliding from the screen into the faces of the audience and more.

Several songs (like The Model/Das Modell, Neon Lights/Neonlicht and Die Mensch-Maschine) were performed with both English and German verses. Some of the songs were updated for today; Radioactivity mentioned Fukushima, and the Spacelab video zoomed in on Iceland, to applause from the audience, before ending with a flying saucer landing somewhere near Düsseldorf. Computer World had a particular resonance in the wake of recent events, but has not, to date, been rewritten to mention the NSA.

It was the first time I had seen Kraftwerk since their Melbourne show in 2003 (which didn't have 3D graphics, though otherwise was spectacular), and was well worth the trip. say what you will, Kraftwerk know how to create a spectacle, a multi-sensory celebration of a (slightly obsolescent) modernity. (There are some photos here, though of course the 3D effects just show up as noise in them.)

2013/2/9

Wolfgang Flür, former member of Kraftwerk, recently saw a performance by the current incarnation of the legendary band, and wrote a review of it:

Remembering our appearances during the 70s and the 80s, so much had moved on. But I understand that today's Kraftwerk fans won't be able to sense this. We used to move; these robots don't. The non-performance of Kraftwerk Mark III made me yawn; the concert went on too long. Thirty minutes less might haved worked, perhaps. But performing as Kraftwerk seemed to offer no joy to the four people who had to be Kraftwerk.

The whole spectacle appeared to me like a farewell-tour for ever. The guy [Stefan Pfaffe] who replaced Florian three years ago has latterly been replaced with a figure whose name is hard to keep in mind [Falk Grieffenhagen], and the turnover of music-workers is becoming quicker and quicker. At Ralf’s age, if he has become Grot – the alerter of the machines in Fritz Lang’s Metropolis – he may find it hard to get new cogs who agree to examination. In some ways, Kraftwerk's story has become a bit like Goethe’s Zauberlehring, The Sorcerer's Apprentice. The sorcerer had activated something all those years ago, and maybe now he can't stop it. The musique is non-Stop. The Volkswagen runs and runs and runs and runs...

2009/10/10

Simon Reynolds has a piece in the Graun about the history of synthpop in 1980s Britain:

In some ways the crucial word in synth-pop isn't "synth" but "pop". The British groups who took over the charts at the dawn of the 80s were catchy and concise. Here they followed the lead of Kraftwerk, who were not only the first group to make a whole conceptual package/weltanschauung out of the electronic age, but were sublime tunesmiths. It's righteous that Kraftwerk's long-awaited remastered catalogue is getting reissued at almost the same time as the long-awaited remastered catalogue of the Beatles, because Hütter & Co rival the Fab Four for both their transformative impact on pop and their melodic genius... Equally inspiring to the synth-pop artists was Kraftwerk's formality: their grey suits and short hair stood out at a time of jeans and beards and straggly locks, heralding a European future for pop, a decisive break with America and rock'n'roll.

Synth-pop went through two distinct phases. The first was all about dehumanisation chic. That didn't mean the music was emotionless (the standard accusation of the synthphobic rocker), but that the emotions were bleak: isolation, urban anomie, feeling cold and hollow inside, paranoia... The second phase of synth-pop reacted against the first. Electronic sounds now suggested jaunty optimism and the gregariousness of the dancefloor, they evoked a bright, clean future just round the corner rather than JG Ballard's desolate 70s cityscapes. And the subject matter for songs mostly reverted to traditional pop territory: love and romance, escapism and aspiration. The prime movers behind synth-pop's rehumanisation were appropriately enough the Human League (just check their song titles: Open Your Heart, Love Action, These Are The Things That Dreams Are Made Of).

"Electro" in the early-90s meant cutting-edge, the future-now; nowadays "electro" refers to the kind of sounds that lit up hipster bars in east London through this past decade and then went mainstream this year with La Roux and Lady Gaga, which is to say synthetic pop that doesn't use the full capacity of the latest digital technology, and is therefore almost as quaint as if it were made using a harpsichord.The article ties in with a BBC4 documentary titled Synth Britannia, which airs next week.

2006/1/5

Michael Chorost, born partially deaf, completely lost his hearing in his mid-30s, depriving him of the pleasure of listening to his favourite piece of music (Ravel's Boléro; one of the few pieces which his condition allowed him to appreciate). He was fitted with a "bionic ear", an implant that processes sound and converts it into neural impulses, at a resolution just good enough to understand speech, though nowhere near enough to appreciate music. So he studied up on neurology, music and psychoacoustics, liaised with experts around the world and hacked the implant's firmware to let him enjoy music again:

When the device was turned on a month after surgery, the first sentence I heard sounded like "Zzzzzz szz szvizzz ur brfzzzzzz?" My brain gradually learned how to interpret the alien signal. Before long, "Zzzzzz szz szvizzz ur brfzzzzzz?" became "What did you have for breakfast?" After months of practice, I could use the telephone again, even converse in loud bars and cafeterias. In many ways, my hearing was better than it had ever been. Except when I listened to music.

About a year after I received the implant, I asked one implant engineer how much of the device's hardware capacity was being used. "Five percent, maybe." He shrugged. "Ten, tops." I was determined to use that other 90 percent. I set out on a crusade to explore the edges of auditory science. For two years tugging on the sleeves of scientists and engineers around the country, offering myself as a guinea pig for their experiments. I wanted to hear Boléro again.

I suggested rebooting and sampling Boléro through a microphone. But the postdoc told me he couldn't do that in time for my plane. A later flight wasn't an option; I had to be back in the Bay Area. I was crushed. I walked out of the building with my shoulders slumped. Scientifically, the visit was a great success. But for me, it was a failure. On the flight home, I plugged myself into my laptop and listened sadly to Boléro with Hi-Res. It was like eating cardboard.

Hold on. Don't jump to conclusions. I backtrack to 5:59 and switch to Hi-Res. That heart-stopping leap has become an asthmatic whine. I backtrack again and switch to the new software. And there it is again, that exultant ascent. I can hear Boléro's force, its intensity and passion. My chin starts to tremble. I open my eyes, blinking back tears. "Congratulations," I say to Emadi. "You have done it." And I reach across the desk with absurd formality and shake his hand.But being able to hear Boléro again wasn't the end of it; with his new hearing, Chorost started getting into the music that he hadn't been able to hear before, and he's confident that it will improve further:

In his studio, Rettig plays me Ravel's String Quartet in F Major and Philip Glass' String Quartet no. 5. I listen carefully, switching between the old software and the new. Both compositions sound enormously better on 121 channels. But when Rettig plays music with vocals, I discover that having 121 channels hasn't solved all my problems. While the crescendos in Dulce Pontes' Cançào do Mar sound louder and clearer, I hear only white noise when her voice comes in. Rettig figures that relatively simple instrumentals are my best bet - pieces where the instruments don't overlap too much - and that flutes and clarinets work well for me. Cavalcades of brass tend to overwhelm me and confuse my ear.

And some music just leaves me cold: I can't even get through Kraftwerk's Tour de France. I wave impatiently to Rettig to move on. (Later, a friend tells me it's not the software - Kraftwerk is just dull. It makes me think that for the first time in my life I might be developing a taste in music.)Amazing stuff.

(via bOING bOING) ¶ 0

2003/9/15

I picked up a copy of New Waver's The Defeated. It's basically techno (in the casual sense of the word) with spoken-word samples from suicide hotlines, medical reports, documentaries about natural selection, football commentary and self-help tapes on how to be a winner; some of it sounds like some of SNOG's early interludes.

Words don't do justice to how profoundly depressing a listen it is; in fact, it is probably the most depressing thing I have ever heard. Compared to New Waver, Thom Yorke is a veritable Pollyanna and Ian Curtis' bleakest lyrics are positively life-affirming. Much has been said about the existential-crisis-inducing potential of post-rock, but this even outdoes A Silver Mt. Zion in that department. Perhaps it's the way the bleak realities of the words subliminally penetrate your consciousness under the repetitive techno beats that does it. Anyway, I was feeling quite cheerful last evening; then I listened to the whole thing, and by the end, I went away with the feeling that life is a pointless, Sisyphean ordeal from which the only reprieve is death.

And then I put on Stereolab's People Do It All The Time and felt a lot better.

Update: And here is New Waver's Kraftwerk tribute MP3 album.

2003/1/30

The Kraftwerk gig was excellent. I showed up and made my way to the balcony, finding a spot with a good view of the stage, as David Thrussell was playing all sorts of weird tunes. Then the DJ stopped, and things were quiet for some minutes, except for the crowd yelling and stamping.

Then the Metro was filled with the sound of an old-fashioned speech synthesizer uttering bits of German, and the curtain rose, revealing four middle-aged men standing behind consoles (and looking not unlike characters from some Star Trek-like TV show).

They played Computerworld and the projection screen glowed cathode-ray green (older readers may remember this colour); they also did Pocket Calculator, with an animation of a calculator, their (quite topical) anti-nuclear protest song Radioactivity, a version of Neon Lights with a verse in German, and their one song about a pretty girl, The Model.

Then the Metro was filled with the sound of an old-fashioned speech synthesizer uttering bits of German, and the curtain rose, revealing four middle-aged men standing behind consoles (and looking not unlike characters from some Star Trek-like TV show).

They played Computerworld and the projection screen glowed cathode-ray green (older readers may remember this colour); they also did Pocket Calculator, with an animation of a calculator, their (quite topical) anti-nuclear protest song Radioactivity, a version of Neon Lights with a verse in German, and their one song about a pretty girl, The Model.

While they stayed at their workstations, playing keyboards and operating their laptops, visuals were projected on the screen behind them, ranging from the sorts of retrofuturistic computer graphics (lots of wireframes; remember when those were cool and shading was too expensive?) to old stock footage of the Tour de France, train and road travel across Europe and the like.

Their songs varied quite a bit from the recordings; the version of The Robots started with them transposing the main riff into different notes, and went on into some improvisation with new (yet quite fitting) synth lines.

(Oh yes, the consoles they were using looked pretty nifty, consisting of a keyboard of some sort, a foot pedal and a laptop. I wonder whether the keyboard part is an off-the-shelf instrument of some sort, or a box containing various controllers and such, and indeed whether the keyboard is not just a controller for software on the laptop, Kraftwerk being famed for their fondness for Cubase VST.)

(Oh yes, the consoles they were using looked pretty nifty, consisting of a keyboard of some sort, a foot pedal and a laptop. I wonder whether the keyboard part is an off-the-shelf instrument of some sort, or a box containing various controllers and such, and indeed whether the keyboard is not just a controller for software on the laptop, Kraftwerk being famed for their fondness for Cubase VST.)

2002/12/4

I'm half-wishing I was in London tomorrow night; because the Bowlie Nite Christmas special is on, and promises to be a lot of fun. Mind you, if I was, I'd miss the Architecture in Helsinki single launch on Friday night.

Meanwhile, it looks like Kraftwerk are doing a solo gig at the Metro in late January. Wonder how quickly tickets will disappear for that one.

2000/9/15