The Null Device

2009/10/15

Authorities in Colorado are searching the skies after a six-year-old boy went for a joyride in his family's "experimental helium-balloon-powered aircraft".

On Thursday morning, according to the family and officials, the boy got onto the aircraft and detached the rope holding it in place. Sheriff's spokeswoman Eloise Campanella said the boy climbed into the access door and the airborne device took off.

The craft, which is shaped like a flying saucer, has the potential to rise to 10,000 feet, Campanella said. Sheriff's officials last saw the device floating south of Milliken, which is about 40 miles north of Denver.

Star Trek screenwriter Ron Moore reveals one of the long-running TV show's secret: it's not actually science fiction:

He described how the writers would just insert "tech" into the scripts whenever they needed to resolve a story or plot line, then they'd have consultants fill in the appropriate words (aka technobabble) later.

"It became the solution to so many plot lines and so many stories," Moore said. "It was so mechanical that we had science consultants who would just come up with the words for us and we'd just write 'tech' in the script. You know, Picard would say 'Commander La Forge, tech the tech to the warp drive.' I'm serious. If you look at those scripts, you'll see that."What do you mean, you say; of course it's sci-fi; they have robots and laser guns and people in latex alien masks and shots of futuristic corridors, in a way that, say, The West Wing and BBC costume dramas don't. The problem is that, if you got rid of the latex masks and content-free technobabble and moved the plots to 20th-century America (or any period in history; the TV characters are all written as 20th-century Americans anyway), they'd work just as well. Which is why Star Trek (whose original working title, it should be remembered, was "Wagon Train In Space") and other TV shows of its ilk fail at the function of science fiction, which is to explore the effects of radical technological and social change on the human condition. Though science fiction author Charlie Stross puts it better:

I use a somewhat more complex process to develop SF. I start by trying to draw a cognitive map of a culture, and then establish a handful of characters who are products of (and producers of) that culture. The culture in question differs from our own: there will be knowledge or techniques or tools that we don't have, and these have social effects and the social effects have second order effects — much as integrated circuits are useful and allow the mobile phone industry to exist and to add cheap camera chips to phones: and cheap camera chips in phones lead to happy slapping or sexting and other forms of behaviour that, thirty years ago, would have sounded science fictional. And then I have to work with characters who arise naturally from this culture and take this stuff for granted, and try and think myself inside their heads. Then I start looking for a source of conflict, and work out what cognitive or technological tools my protagonists will likely turn to to deal with it.

Star Trek and its ilk are approaching the dramatic stage from the opposite direction: the situation is irrelevant, it's background for a story which is all about the interpersonal relationships among the cast. You could strip out the 25th century tech in Star Trek and replace it with 18th century tech — make the Enterprise a man o'war (with a particularly eccentric crew) at large upon the seven seas during the age of sail — without changing the scripts significantly. (The only casualty would be the eyeball candy — big gunpowder explosions be damned, modern audiences want squids in space, with added lasers!)

The biggest weakness of the entire genre is this: the protagonists don't tell us anything interesting about the human condition under science fictional circumstances. The scriptwriters and producers have thrown away the key tool that makes SF interesting and useful in the first place, by relegating "tech" to a token afterthought rather than an integral part of plot and characterization. What they end up with is SF written for the Pointy-Haired [studio] Boss, who has an instinctive aversion to ever having to learn anything that might modify their world-view. The characters are divorced from their social and cultural context; yes, there are some gestures in that direction, but if you scratch the protagonists of Star Trek you don't find anything truly different or alien under the latex face-sculptures: just the usual familiar — and, to me, boring — interpersonal neuroses of twenty-first century Americans, jumping through the hoops of standardized plot tropes and situations that were clichés in the 1950s.

Recently, the Swiss National Bank held a competition to redesign the Swiss Franc banknotes, and got some very handsome submissions:

Switzerland has probably the best-looking banknotes I've seen; they're as colourful as the Australian ones, but with the fastidiously neat graphic design the Swiss are renowned for (they didn't name Helvetica after the Latin name for Switzerland for nothing, you know).

Steven Levitt and Stephen Dubner, the authors of Freakonomics, have a sequel coming out next week; titled, naturally, Superfreakonomics, it looks like the same winning blend of insights, economic detective stories and at times glib reductionism:

Thus in the new book we learn, for example, that more deaths are caused per mile, in America at least, from drunk walking than drunk driving – so when you drive to a party and get plastered, it's not necessarily a wise decision to leave the car and walk home. We discover that female emergency-room doctors are slightly better at keeping their patients alive than male ones, and that Hezbollah suicide bombers, far from being the poorest of the poor, with nothing to lose, tend to be wealthier and better-educated than the average Lebanese person. There's an artful takedown of the fashionable "locavore" movement: transportation, Levitt and Dubner argue, accounts for such a small part of food's carbon footprint that buying all-local can make matters worse, because small farms use energy less efficiently than big ones.

Their mission to explain the world through numbers alone can give Superfreakonomics an oddly detached feel: major social issues are addressed, then instantly reduced to a statistical parlour game. An interesting section on the transactions between pimps and prostitutes, for example, shows that working with a pimp confers great financial advantages: they're much more helpful to prostitutes than estate agents are to house-sellers, for a start. But it neglects to consider the notion that there might, just possibly, be some negative aspects to the pimp-prostitute relationship. (The authors, apparently aware that they have made it look as if selling sex is the business plan to beat all others, add a helpful clarification: "Certainly, prostitution isn't for every woman.")

One thing Britain won't be short of any time soon is qualified forensic scientists; the country's universities are competing for the pool of science students by laying on forensic science degrees to attract fans of police-procedural TV shows:

Let's call it the CSI Effect: thanks to the uncontrolled proliferation of cop shows focusing on forensic investigation, including Bones, Silent Witness, CSI and its Miami and New York spin-offs, the number of degree courses in forensic science being offered in the UK has rocketed, from just two in 1990 to 285 this year.

The biggest problem, however, is that crime has not kept pace with the explosion in TV detective shows. The government-owned Forensic Science Service currently finds 1,300 scientists sufficient for its crime-solving needs. The UK's largest private provider, LGC Forensics, employs 500 people. In 2008 alone, 1,667 students embarked on forensic science degree courses. In order to ensure there are enough jobs to go round, more than half of them will have to retrain as serial killers.

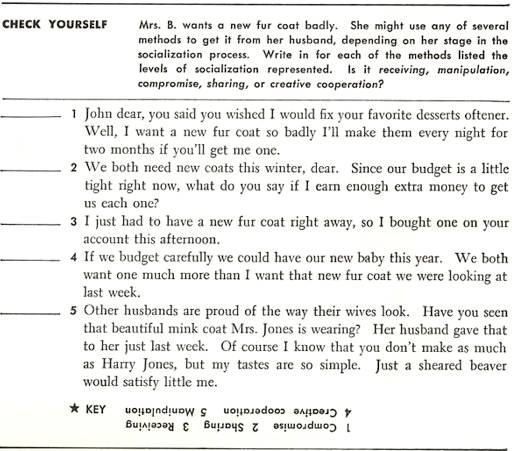

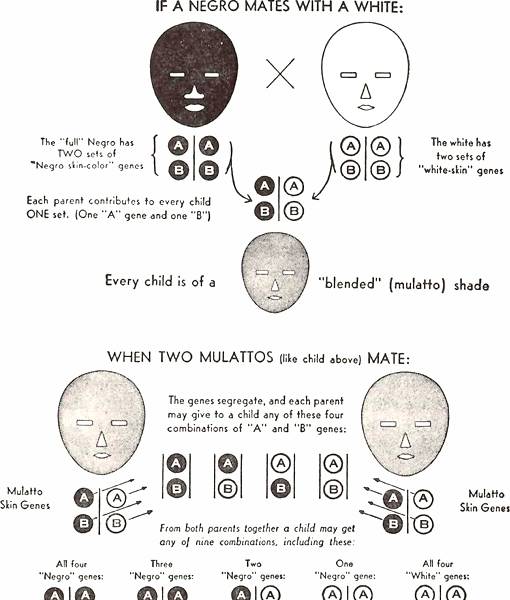

Weren't the 1950s awesome? Exhibit (a): an American high-school marriage-education textbook (from 1962, though culturally part of the conservative 1950s, before the Communists successfully fluoridated the water supply and brought about what is commonly known as The Nineteen-Sixties):

Exhibit (b): a letter written in 1956 to FBI director J. Edgar Hoover by the editor of a Catholic newspaper, concerning the moral threat posed to America's youth by a young singer named Elvis Presley:

But eyewitnesses have told me that Presley's actions and motions were such as to rouse the sexual passions of teenaged youth. One eye-witness described his actions as “sexual self-gratification on the stage," — another as “a striptease with clothes on." Although police and auxiliaries were there, the show went on. Perhaps the hardened police did not get the import of his motions and gestures, like those of masturbation or riding a microphone.

I do not report idly to the FBI. My last official report to an FBI agent in New York before I entered the U.S. Army resulted in arrest of a saboteur (who committed suicide before his trial). I believe the Presley matter is as serious to U.S. security. I am convinced that juvenile crimes of lust and perversion will follow his show here in La Crosse.

(via Boing Boing, MeFi) ¶ 1