The Null Device

Posts matching tags 'depression'

2012/3/8

When testing drugs for treating depression on lab mice, it is important to have ways of determining whether or not a mouse is depressed, or suffering from the mouse equivalent of depression. Not surprisingly, mice deemed to be depressed are the ones which give up and stop struggling when faced with difficulty, and which get little joy from life:

Forced swimming test. The rat or mouse is placed into a cylinder partially filled with water from which escape is difficult. The longer it swims, the more actively it is trying to escape; if it stops swimming, this cessation is interpreted as depressionlike behavior, a kind of animal fatalism.

Sugar water preference. The preference an animal shows for sugar water is taken as an indication of its ability to derive pleasure, a quality that is missing in depression. Most rodents, when given two identical-looking sources of water, will drink much more of the sweetened water than the plain water. Rodents exposed to chronic stress or whose brains have been manipulated show no such preference.(Previously: Scientists create a mouse that's permanently happy.)

(via Boing Boing) ¶ 0

2010/2/3

Life imitates New Waver lyrics yet again: A psychological study at Leeds University has found a connection between depression and heavy internet use:

The authors found that a small number of users had developed a compulsive internet habit, replacing real life social interaction with online chat rooms and social networking sites.

They classed 18 respondents - 1.2% of the total - as "internet addicts". This group spent proportionately more time on sex, gambling and online community websites... The internet addicts were significantly more depressed than the non-addicted group, with a depression score five times higher.Of course, the whole concept of "internet addiction" is a dubious one, and often tinged with tabloid-style moral panic, so there's a danger that the advocates of the "internet addiction" industry will wave this around as proof, ignoring the fact that the addictive behaviours there are more usefully described as gambling and/or pornography addiction.

The report does not put forward any causal links between heavy internet use and depression. Do specific patterns of internet use weaken social contacts, contributing to depression, or do depressed people use the internet to self-medicate?

Also, the inclusion of online community websites along with sex and gambling websites seems somewhat dubious; while the latter are masturbatory replacements for natural stimuli, especially those one leading an impoverished life may lack, can one really imply that social community sites substitute for and weaken social ties rather than facilitating them? I recall a study from a few years ago which showed that users of social web sites actually have stronger social connections, and improved wellbeing as a result of those. Though it is always possible that various characteristics of particular social websites (which may be influenced by their design and/or emergent from organic patterns of use) influence their ability to facilitate psychologically useful social ties.

2009/4/20

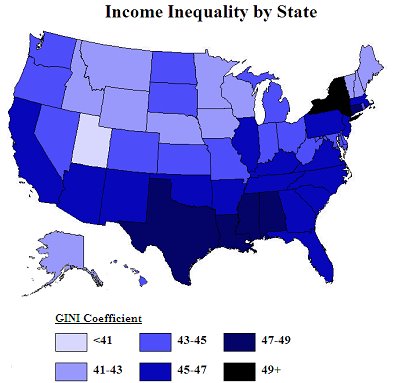

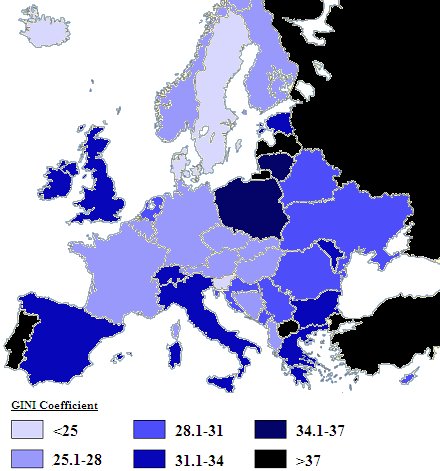

The Map Scroll blog has a map of the Gini coefficients of all the US states, and another one of Europe.

The Gini coefficient is a number from 0 to 1 representing the equality or inequality of income distribution in an economy; 0 is theoretical absolute equality, and 1 is one person having everything and everyone going without. In practice, it varies from about 0.2 to about 0.7.

According to it, Europe ranges from the mid-.20s to the high .30s, with a few outliers in the low 40s. At the most egalitarian end, unsurprisingly, are the Jante states of Denmark and Sweden, as well as Iceland (perhaps surprisingly, if it's meant to have been an experiment in cut-throat neoliberalism). Things get more inequitous into Norway, Finland, France, Germany and Switzerland (which stays under .28, despite being home to a lot of the global super-rich), and then on to Italy, Spain, Britain and Ireland, and beyond that, Poland and Lithuania. The most unequal country in Europe is Turkey, which has a Gini coefficient of 0.436, somewhere between Guyana and Nigeria, or, if you prefer, Delaware and Hawaii.

The United States is, unsurprisingly, a lot less egalitarian in income than Europe. American states' Gini coefficients range from 0.41 (the solidly Mormon state of Utah, whose state emblem is the beehive, has a Gini coefficient equivalent to Russia's) to a whopping 0.537 in the District of Columbia (comparable to the Honduras). Other states are twinned with parts of the developing world; Alabama and Mississippi are most like Nepal, California has the income distribution of Rwanda, and New York, barely under the .5 mark, is twinned with Costa Rica. According to the article, this is an astonishing state of affairs for a developed country:

According the the CIA World Factbook (table compiled here), the lowest Gini score in the world is Sweden's, at .23, followed by Denmark and Slovenia at .24. The next 20 countries are all in either Western Europe or the former Communist bloc of Eastern Europe. The EU as a whole is at .307. Russia has the highest number in Europe (.41); Portugal is the highest in Western Europe (.38). Japan is at .381; Australia is .352; Canada is .321.

And then there is the United States, sandwiched between Cote d'Ivoire and Uruguay at .450. Not counting Hong Kong (.523), the US is a complete loner among developed countries. In fact, as you can see from the map above, there is no overlap between any single US state and any other developed country; no state is within the normal range of income distribution in the rest of the developed world. Here's a list of the states with their Gini index numbers, and the country where income distribution is most comparable in parentheses:Other interesting maps on the site include a map of religious nonbelief in the UK (which points out that Scotland and Northern Ireland are the most religious, and asks whether that correlates to the Scots-Irish roots of the US "Bible belt"), of antidepressant use in England and Wales (summary: it's grim up north, and in Cornwall too; either that or Londoners prefer a line of coke), and one suggesting that, as global warming advances, Australia is ecologically fux0red.

2008/2/29

Striking another blow against the modern idea that 100% cheerfulness is attainable or desirable, an expert on mood disorders at King's College argues that depression may be good for you:

The fact it has survived so long - and not been eradicated by evolution - indicates it has helped the human race become stronger.

"I have received e-mails from ex-sufferers saying in retrospect it probably did help them because they changed direction, a new career for example, and as a result they're more content day-to-day than before the depression."

Aristotle believed depression to be of great value because of the insights it could bring. There is also an increased empathy in people who have or have had depression, he says, because they become more attuned to other people's suffering.

2008/1/16

An expatriate Briton in America was diagnosed as clinically depressed, prescribed antidepressants, and even scheduled for shock therapy, before doctors realised that he was not depressed, just British. (Or, to be precise, English.)

Doctors described Farthing as suffering from pervasive negative anticipation: a belief that everything will turn out for the worst, whether it's trains arriving late, England's chances of winning any national sports events, or his own prospects of getting ahead in life. The doctors reported that the satisfaction he seemed to get from his pessimism was particularly pathological.

'They put me on everything -- lithium, Prozac, St. John's wort,' Farthing says. 'They even told me to sit in front of a big light for half an hour a day or I'd become suicidal. I kept telling them this was all pointless, and they said that was exactly the sort of attitude that got me here in the first place.'The symptomology of Britishness, it seems, is indistinguishable from that of depression (the next edition of the DSM will presumably contain an entry for it). Luckily, both conditions are treatable.

(via Mind hacks) ¶ 0

2007/4/5

The Guardian has an excerpt from a recent book by Barbara Ehrenreich, which postulates that the rise of subjective individual self-awareness and the decline of the collective celebrations common in mediæval times may have touched off an epidemic of depression we've been living in ever since:

And very likely the phenomena of this early "epidemic of depression" and the suppression of communal rituals and festivities are entangled in various ways. It could be, for example, that, as a result of their illness, depressed individuals lost their taste for communal festivities and even came to view them with revulsion. But there are other possibilities. First, that both the rise of depression and the decline of festivities are symptomatic of some deeper, underlying psychological change, which began about 400 years ago and persists, in some form, in our own time. The second, more intriguing possibility is that the disappearance of traditional festivities was itself a factor contributing to depression.

One approaches the subject of "deeper, underlying psychological change" with some trepidation, but fortunately, in this case, many respected scholars have already visited this difficult terrain. "Historians of European culture are in substantial agreement," Lionel Trilling wrote in 1972, "that in the late 16th and early 17th centuries, something like a mutation in human nature took place." This change has been called the rise of subjectivity or the discovery of the inner self and since it can be assumed that all people, in all historical periods, have some sense of selfhood and capacity for subjective reflection, we are really talking about an intensification, and a fairly drastic one, of the universal human capacity to face the world as an autonomous "I", separate from, and largely distrustful of, "them".

But the new kind of personality that arose in 16th- and 17th-century Europe was by no means as autonomous and self-defining as claimed. For far from being detached from the immediate human environment, the newly self-centered individual is continually preoccupied with judging the expectations of others and his or her own success in meeting them: "How am I doing?" this supposedly autonomous "self" wants to know. "What kind of an impression am I making?"If this hypothesis is correct, then the epidemic of depression and mental illness that began in the 1600s (which Ehrenreich provides supporting evidence for, in historical records) is a side-effect of a step in the evolution of human psychology that began at around that time, with the pressures of communication, trade and social organisation dragging the human mind kicking and screaming from a sleepy collective life to a more dynamic way of living. In this case, a lot of the anxiety, angst and low-level distress people feel routinely is not a result of human nature, but rather human nature reacting against "unnatural" circumstances. Small wonder that many have sought relief in an annihilation of the self, from hippie communes to Communist utopias, from meditation to severe religious submission, from the Arcadian pastoral utopias throughout art (Tolkien, William Morris and the Arcade Fire to name three examples off the top of my head) to the transcendental nihilism of drugs (take, for example, Lou Reed wishing he had been born "a thousand years ago" in Heroin).

So where does that leave us? Perhaps, given enough time (hundreds if not thousands of years), human psychology will evolve into depression-resistant directions, assuming that some kind of technological catastrophe doesn't cut the process short. Genetic evolution is slow, but cultural evolution is faster, and it could be argued that our technologies and cultural institutions are part of the "extended phenotype" of humanity; that the invention of antidepressant drugs is an adaptation to these changes in our environment. It's a crude, reactionary adaptation, merely treating the symptoms; though there is hope on the horizon. There has recently been a lot of focus on the study of the psychology of happiness, and what factors make for environments conducive to sustainable happiness. With any luck, this will lead to improvements in areas from urban planning to social policy to economics.

Then again, if the hypothesis is true, would it be possible to somehow get the best of both worlds? Could one have the happy, fulfilling collective connectedness people (allegedly) had before the 16th century, whilst retaining the gains made since then? Or is the very presence of subjective thought, the demarcation between the self and the collective, poisonous?

(On the other hand, L. Ron Hubbard claims that depression comes from humanity's early ancestor, the clam, and the tension between the desire to open and close its hinge.)

2006/8/11

While antidepressants have been popular in the West for some decades, there was originally next to no demand for them in Japan, as Japanese culture (which is based on Buddhism) had no concept of depression as an illness. Then, in 1999, a Japanese pharmaceutical company introduced the concept of depression to Japan, coining a name for it: "kokoro no kaze", literally, "common cold of the soul":

For 1,500 years of Japanese history, Buddhism has encouraged the acceptance of sadness and discouraged the pursuit of happiness -- a fundamental distinction between Western and Eastern attitudes. The first of Buddhism's four central precepts is: suffering exists. Because sickness and death are inevitable, resisting them brings more misery, not less. ''Nature shows us that life is sadness, that everything dies or ends,'' Hayao Kawai, a clinical psychologist who is now Japan's commissioner of cultural affairs, said. ''Our mythology repeats that; we do not have stories where anyone lives happily ever after.'' Happiness is nearly always fleeting in Japanese art and literature. That bittersweet aesthetic, known as aware, prizes melancholy as a sign of sensitivity.

This traditional way of thinking about suffering helps to explain why mild depression was never considered a disease. ''Melancholia, sensitivity, fragility -- these are not negative things in a Japanese context,'' Tooru Takahashi, a psychiatrist who worked for Japan's National Institute of Mental Health for 30 years, explained. ''It never occurred to us that we should try to remove them, because it never occurred to us that they were bad.''

Direct-to-consumer drug advertising is illegal in Japan, so the company relied on educational campaigns targeting mild depression. As Nakagawa put it: ''People didn't know they were suffering from a disease. We felt it was important to reach out to them.'' So the company formulated a tripartite message: ''Depression is a disease that anyone can get. It can be cured by medicine. Early detection is important.''It is arguable that Japan may have needed a concept of, and treatment for, depression, with its suicide rate being over twice the levels experienced in Western countries. Though one can't help but wonder whether the cultural change brought by introducing the concept of depression will result in Japanese culture losing something and becoming more like everywhere else (which is to say McWorld). And, if so, whether or not the gains will outweigh any loss.

2005/8/15

Dust off your anoraks, because a new alternative club night is opening in London; the night, Feeling Gloomy, will play only miserablist anthems. Patrons can probably expect the usuals: The Smiths, Leonard Cohen, and such, as well as a few surprises:

And Wake Up Boo, by the Boo Radleys, which far from being an end-of-the-summer anthem is apparently "about death". But just when you think the play list sounds like a trip down memory lane for those who were students or Indie kids in the mid 90s, he adds that East 17's Stay Another Day puts in an appearance. When I suggest that that particular song is just 'slushy stuff' I am told it qualifies because it is about the suicide of the songwriter's brother.

"I just created a night that I would want to go to and for people who maybe have stopped going to clubs because they don't like the music. When a flyer for a club says 'sexy, funky, fun', it makes me annoyed. It's not sexy, it's drunk girls in mini-skirts being sick."The night will also serve cheese and pickle sandwiches and cups of tea; part of the proceeds will go to the Depression Alliance.

2005/8/3

2005/1/21

A tutor at Cardiff University has determined mathematically that the 24th of January (i.e., this coming Monday) is the most depressing day of the year:

The formula for the day of misery reads 1/8W+(D-d) 3/8xTQ MxNA.

Where W is weather, D is debt - minus the money (d) due on January's pay day - and T is the time since Christmas.

Q is the period since the failure to quit a bad habit, M stands for general motivational levels and NA is the need to take action and do something about it.

2002/5/23

Research at New York University claim that semen is an antidepressant absorbed through the skin, and that women who engage in unprotected sex are consequently less likely to suffer from depression. I can see this giving rise to a million dodgy pick-up lines already... (via rotten.com)

2002/4/18

Romantic Love Considered Harmful: New research shows that teenagers who are preoccupied with romantic thoughts in their adolescence are more likely to suffer depression later in life. (via FmH)

2001/7/26

Poetry by suicidal poets contains telltale signs of suicidal tendencies, in the form of linguistic patterns. Researchers in the US applied computer analysis techniques to poetry by poets who took their own lives, including Sylvia Plath, as well as a control group of non-suicidal poets, and determined that the suicidal poets used many more singular first-person references, and fewer words associated with interpersonal communication, thus suggesting detachment and self-absorption. Surprisingly, emotional words such as "love" and "hate" did not vary significantly between the two words.

2001/2/19

Scare meme of the day (or of a few days ago anyway): Falling in love is bad for your psychological health; at least if you're a teenager. Adolescents in the throes of romantic involvement and under the influence of phenylethylamine have been found to be more susceptible to depression, delinquency and drug abuse. Remember kids: Just Say No. (via Rebecca's Pocket)

2000/10/17

Life is unfair, kill yourself or get over it: According to a recent survey, Britain is a dismal place, with 1/3 of the population feeling "downright miserable", 1/4 believing that life is unfair, and one in 10 believing that they would be better off dead. Then again, is that really saying anything that numerous British indie bands haven't already said in many ways?

2000/8/11

NME have published a list of the 10 most depressing albums of all time. Not surprisingly, both Joy Division albums are on this list; oddly enough, the Smiths don't feature even once.