The Null Device

Posts matching tags 'economics'

2015/3/21

There's a piece in the Telegraph (yes, the Torygraph) about the London housing crisis; the prognosis is not good. Basically, it's going to get much worse. Private tenants are, of course, screwed as they've always been, and there'll be no relief as the Invisible Hand Of The Free Market tightens the screws on them (and this will increasingly apply further from London, encompassing the entire South-East of England; basically, anyone living anywhere where a commute to London is not utterly soul-crushingly miserable will be paying through the nose for the privilege). The lucky few who have managed to grab a tenuous grip on the bottom rungs of the housing ladder as it started to pull away are also not out of the woods; as interest rates start to rise, many will find it difficult to keep up and some will fall off. As for their houses, and the thousands of flats being built around London, they're unlikely to help: virtually all of them (other than the super-premium ones bought as investments and “bubble-wrapped” by foreign investors) will be snapped up by buy-to-let landlords, flush with cash from their healthily growing rents and looking to build up their portfolios further, aided by preferential mortgage terms. The end result looks pretty bleak for everyone. Well, everyone with the exception of landlords, for whom life is good and can only get better:

The Joseph Rowntree Foundation extrapolates and suggests that by 2040 private rents will rise by more than twice as much as incomes, resulting in a majority of future private renters in England living in poverty. Social renting, currently the tenure of one in seven people, will house only 10 per cent of the population by 2040.And don't expect relief from any of the major political parties; none of them have submitted any proposals for fixing things, save for ones which would further push housing prices up, and keep the cash flowing into the pockets of landlords. Perhaps the fact that a third of MPs are buy-to-let landlords has something to do with their collective reluctance to in any way interrupt the party?

The elephant in the room is the assumption that the normal state of affairs is owning one's own home; this is a peculiarly Anglo-Saxon ideal, perhaps imported from the broad suburbias of the United States, where the average working stiff could buy and pay off a detached bungalow (at least in theory). Whereas in a lot of other countries, renting is seen as the normal state of affairs, in the UK, people live with the belief—or delusion—that it's a temporary state of affairs, a stepping stone on the way to being a fully-fledged adult member of the property-owning democracy. John Steinbeck famously said that socialism never took off in the United States because poor Americans, in their eternal optimism, saw themselves not as exploited proletarians but as temporarily embarrassed millionaires; perhaps in Britain, the idea of rent control, regulation (even such supposedly uncontroversial regulations as preventing landlords from evicting tenants in revenge for raising a fuss about problems), or even not rigging the system to funnel billions of pounds of taxpayers' cash to landlords, stems from a similar sentiment: that the hard-pressed renter, paying 60% of their income for a mouldy bedsit, will somehow eventually become a property owner, and, ultimately, graduate to the hallowed echelon of landlords, funding their golden years from the property portfolio that they will, in the fullness of time, inevitably own?

2014/10/7

A new study has looked at why fewer women cycle in the United States than in the Netherlands, and found that it has less to do with an often stated Anglophone culture of cycling-as-macho-extreme-sport, and more to do with women in the US being too busy with domestic chores for the luxury of cycling:

In short, despite years of progress, American women’s lives are still disproportionately filled with driving children around, getting groceries, and doing other household chores – housework that doesn’t lend itself easily to two-wheeled transportation. It turns out that women may be more likely to bike in the Netherlands because Dutch culture is giving them more time to do so.Of course, the fact that in the Netherlands it is possible to carry anything from a toddler to a bag of groceries on a bakfiets is one factor, as is the fact that Dutch children are more likely to go to school by themselves (often on their own bicycles) than be dropped off in Mom's SUV; a lot of it, though, comes down to more traditional gender-based divisions of labour in the US and that hyperefficient Anglocapitalist labour market leaving those who get stuck doing the chores (i.e., usually the women) with less time for the luxury of cycling:

Dutch women can use bikes to get around because they are less pressed for time than American women, in three fundamental ways. First, thanks to family-friendly labour policies like flexitime and paternity leave, Dutch families divide childcare responsibilities much more evenly than American families. Second, work weeks in the Netherlands are shorter. One in three Dutch men and most Dutch women work part-time, and workers of either gender work fewer hours than Americans.Of course, this is a piece in the Grauniad; were it in, say, the Financial Times or the Economist, it may well say that large numbers of female cyclists is a symptom of an inefficient economy, one which fails to extract the maximum amount of productivity from its labour force; indeed, one can imagine a report from a neoliberal think tank claiming that women on bicycles are a drag on productivity.

2014/4/11

Alex Proud, who previously wrote about the Shoreditch-modelled gentrification and sanitisation of the down-at-heel parts of London, has a new article about the end state of this process of gentrification and the future of hyper-gentrified London, a homogeneously rich, clean, and dull, place, with all the edginess and excitement of Geneva or central Paris, a city of "joyless Michelin starred restaurants and shops selling £3,000 chandeliers":

Two decades on and you can play a nostalgic little game where you remind yourself what groups London’s inner neighbourhoods were known for 20 years ago. Hampstead: intellectuals; Islington: media trendies; Camden: bohemians, goths and punks; Fulham: thick poshos who couldn’t afford Chelsea; Notting Hill: cool kids; Chelsea: rich people. Now, every single one of these is just rich people. If you want to own a house (or often just a flat) in these places, you need a six figure salary or you can forget it. And, for anyone normal, that means working in finance.

Inner Paris is a fairytale for wealthy people in their fifties (and outer Paris looks like Stalingrad with ethnic strife) while Geneva has dispensed with the poor altogether. As a result, both cities are safe, pretty and rather boring places to live – and soon London will be too.The article is a fine rant, dripping with bons mots like “Bitcoins for oligarchs”, “like Jay-Z as reimagined by someone who works at Goldman Sachs”, and “the bastard offspring of Kirstie Allsopp and Ayn Rand”; the prognosis is not hopeful for London either:

Why? Because the financiers who can afford inner London neighbourhoods are not cool. Visit Canary Wharf at on any weekday lunchtime and watch the braying, pink-shirted bankers disporting themselves. Not cool. Peruse the shops at Canary Wharf. From Gap to Tiffany’s, they’re all chains stores and you could be anywhere wealthy, safe and dull in the world. Rich people like making money and spending it on dull, expensive things. That’s what they do – and they’re very good it. But being a high-end cog in the machine is not cool.

In the short term, our city’s young creative class will continue to move further and further out. Is New Cross the new Peckham? Is Walthamstow the new Dalston? But there are limits to this: there’s not much of a vibe in Ruislip and there never will be; really, the cool inner suburb ship sailed in 2005. So, when you’re stuck out amongst the pebble-dashed semis of Zone 4, miles from a centre that’s mainly chain shops, boutiques for the tacky rich and restaurants you can’t afford or even book, you might start wondering if the World’s Greatest City (TM) really is for you. Then maybe you’ll visit friends, somewhere like Bristol or Newcastle or Leeds or Glasgow. And maybe you’ll discover that there you can buy a house that’s walking distance to a centre full of shops that cater to you, restaurants that want your custom and pubs and clubs whose prices wouldn’t make someone in Gstaad blanch... Perhaps London’s craven fealty to the ghastly rich will finally accomplish what no government policy ever has – it will rejuvenate our provincial cities.Though chances are, the cities with fast links to London will end up hypergentrified as well; Brighton (or “London-by-the-sea”, as some call it) is well on the way to going there, and some speculate that places like Margate (one hour from London along a partly high-speed railway, and already sprouting vintage shops and a modern art gallery amongst the everyday-is-like-Sunday shabbiness) could end up following suit. Birmingham, meanwhile, might jump from never-quite-fashionable to bourgeois luxury for the new-economy elite when HS2 arrives, allowing those who aren't fully-fledged partners to afford somewhere within an easy commute of Canary Wharf.

Proud blames this state of affairs on a system rigged to pander to the beneficiaries of this state of affairs—house-flippers, buy-to-let landlords, ex-Soviet oligarchs looking for somewhere to park their wealth—at the expense of the little people to whom it is made clear that the city does not belong, and who are gradually squeezed further out, towards the periphery and beyond; who still hold onto their shrinking, expensive foothold on the precious land inside the M25, believing that it's stil worth it because of the aura of brilliance surrounding the idea of London; an aura increasingly based in nostalgic delusion, and one which can't last.

Readers of the Guardian or New Statesman will have seen this story numerous times, from different angles and at different points in time, more or less the same, only with the place names moved slightly further out every year. However, part of the message here is in the medium; Proud is writing in the Daily Telegraph, a paper owned by the Barclay Brothers, long associated with the Conservative Party (it's often nicknamed the Torygraph), and one which one might imagine would be perfectly au fait with the ideals of the Thatcherite “property-owning democracy”. When the Torygraph is publishing articles bemoaning how gentrification is hollowing out and sterilising London, then perhaps it is time to be concerned.

I wonder how much this is due to one of the less-often-quited corollaries of the neoliberal/market-oriented mindset of the recent few decades: the idea that anything of value is traded on a market, and everything is a convertible hard currency, this time applied to cultural capital. It used to be that cultural capital and economic capital were separate spheres, and absolutely not interconvertible. There were no cool rich kids, or those who were hid their economic capital. (The word “cool”, in fact, originated with socially and politically disenfranchised African-Americans; in its original meaning, the word didn't mean chic, fashionable or at the top of the status hierarchy, but refered to an unflappability, an unwillingness to let the constant low-level (and not so low-level) insults and aggressions of an institutionally racist and classist system be seen to get you down; as such, it was, by definition, the riches of the poor, the exclusive capital of those excluded from capital.)

Fast forward to the present day; after Milton Friedman declared everything to be convertible goods in a market. Reagan and Thatcher applied this to economic goods, launching the “Big Bang” of deregulation and the 20-year economic bubble that followed. Then the Clinton/Blair era of the “Third Way” coincided with its own Big Bang, this time deregulating the cultural marketplace; starting off with Britpop and going on to Carling-sponsored landfill indie, New Rave, hipster electro (and indeed the recycling of the term “hipster”, originally meaning a habitué of the grimy jazz-and-heroin demimonde of the Beat Generation, now referring to trust fund kids in limited-edition trainers), yacht rock, chillwave and whatever. The old regulatory barriers between the mainstream and the underground were swept away as surely as the barriers between high-street and investment banks had been a decade earlier; the rise of the internet and the cultural globalisation played a part in it, though the mainstreaming of market values once seen as radical would also have had a hand. Soon everything was in a commodity available on the marketplace; 1960s guitar rock and Mod iconography was revived as Britpop, post-punk, stripped of unmarketable references to Marxism, Situationism and existentialist paperbacks and sexed up, as generic NME-cover “indie”, and we were faced with a multifaceted 80s revival that ran for longer than the 80s. Major-label pop producers used ProTools plug-ins to grunge up their protégés, giving them that authentically lo-fi “alternative” sound, while bedroom producers armed with cheap laptops and cracked software made tracks that sounded as expensively polished as anything heard in a Thatcher-era wine bar. Knowing about Joy Division or Black Flag was no longer a badge of being “hip”, as anyone with an internet connection could do the research; the new shibboleths were evanescent memes, like referencing Hall & Oates right down to the facial hair, or reviving New Jack Swing and calling it “PBR&B”, or the whole Seapunk subculture; currents one wouldn't have caught wind of in time without being connected, and whose cultural value became void once the wider world heard of them.

This coincided with the dismantling of free education, the rise in income inequality, and the gentrification of “cool” areas full of the young and creative, and soon it was a good thing that having economic and social capital didn't bar one from cultural capital, because having a trust fund was increasingly a prerequisite. If Mater and Pater bought you a flat near London Fields for your 18th birthday, and if you had a reserve of money to spend while you “found yourself”, and the likelihood of being able to land an internship on a career track in the media once your Southern-fried-hog-jowls-in-katsu-curry food truck failed or you got bored of playing festivals with your respectably rated bass-guitar-and-Microkorg duo, then you had the freedom to explore and develop, and that development could take a number of forms; travelling the world's thrift shops, picking up cool records and playing them at your DJ night, spending the time you don't need to work for money getting good at playing an instrument (and recent UK research shows that people in wealthier areas tend to have better musical aptitude), or just growing a really lush beard. With the rolling back of the welfare state and the "race to the bottom" in wages, these quests for self-actualisation are once again the preserve of the gentry; it's rather hard to develop your creative voice when you're on zero-hour contracts, and spend all your time either working in shitty jobs, looking for work, or commuting from where you can afford to live. And so economic capital has colonised cultural capital, and what passes for “cool” now belongs to those with money. It's not quite like a Gavin McInnes troll-piece about the coke-addicted bankers' scions who form the Brooklyn scene or a Vice_Is_Hip parody tweet about the coolest bar in the Hamptons or the latest sartorial trends from Kuwait's hippest princelings, but those are looking less and less unbelievable.

The question is, what happens in the end? Will cultural capital converge with economic capital, and “cool” be redefined to be a sort of cultural noblesse oblige, a manifestation of wealth and status, or will, as Proud suggest, the whole thing collapse into a cultural low-energy state of tidy tedium?

2014/1/5

As their ranks and fortunes grow, the world's super-rich have been ploughing increasing amounts of money into buying art, often motivated primarily by its investment value; a Picasso, you see, is not so much a pretty object to hang on the wall of your grouse-hunting lodge in the Scottish Highlands, but rather a sort of high-denomination banknote. As such, airports in countries like Switzerland, Luxembourg and Singapore are sprouting networks of high-security art warehouses for storing their wealthy clients' collections; these remain airside, where import duties are not payable, and now are sprouting facilities to make it easier for the artefacts (which, for legal purposes, are still “in transit”) to be exhibited (though only to potential buyers, not members of the great unwashed):

The goods they stash in the freeports range from paintings, fine wine and precious metals to tapestries and even classic cars. (Data storage is offered, too.) Clients include museums, galleries and art investment funds as well as private collectors. Storage fees vary, but are typically around $1,000 a year for a medium-sized painting and $5,000-12,000 to fill a small room.

The early freeports were drab warehouses. But as the contents have grown glitzier, so have the premises themselves. A giant twisting metal sculpture, “Cage sans Frontières”, spans the lobby in Singapore, which looks more like the interior of a modernist museum or hotel than a storehouse. Luxembourg’s will be equally fancy, displaying concrete sculptures by Vhils, a Portuguese artist. Like Singapore and the Swiss it will offer state-of-the-art conservation, including temperature and humidity control, and an array of on-site services, including renovation and valuation.

The idea is to turn freeports into “places the end-customer wants to be seen in, the best alternative to owning your own museum,” says David Arendt, managing director of the Luxembourg freeport. The newest facilities are dotted with private showrooms, where art can be shown to potential buyers. To help expand its private-client business, Christie’s, an auction house, has leased space in Singapore’s freeport (which also houses a diamond exchange). The wealthy are increasingly using freeports as a place where they can rub shoulders and trade fine objects with each other. It is not uncommon for a painting to be swapped for, say, a sculpture and some cases of wine, with all the goods remaining in the freeport after the deal and merely being shifted between the storage rooms of the buyer’s and seller’s handling agents.

2013/12/23

Websites asking contributors to write for free (“for exposure”) is old-hat, it seems, now supplanted by websites allowing contributors to write for them, in return for a fee; i.e., the old vanity-press business model, now refurbished by Mumsnet (best known as the online forum of “penis beaker” fame):

‘Webchats are actually something Mumsnet often charges for, because they’re such an effective way of promoting things; they tend to get many thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, of page views. In other circumstances (as we were thinking here) we do them on a no-cost basis (on either side) because it’s an issue our audience is interested in, and people who want to campaign on something or drum up interest see it as an opportunity to get their message out.’This blurring of the lines between editorial and advertising (hint: look at the direction the money flows to see which is which) is apparently a symptom of the New Gilded Age; the hollowing-out of the middle class and the erection of a new privileged stratum above its straitened remnants, a stratum differentiated from the unworthy rabble below by the ability to pay to unlock doors and elbow one's way in (see also: the unpaid internships required to start careers in the media and other industries; or, indeed, the abolition of free university education coupled with a bachelor degree becoming the minimum requirement for any work from secretarial work (now rebranded as “PA”) upward). So, naturally, if the indicator of which stratum in society one belongs in is one's (or one's parents') ability to pay, it makes perfect sense for the invisible hand of the free market to raise itself, palm forward, in the faces of the jumped-up serfs who have the temerity to think they have a right to be heard:

Readers suffer because British writing is no longer a meritocracy but becoming a vast system of vanity publishing. Editors are not nurturing talent, but looking for passengers who can pay their own way. As Julie Burchill says, ‘once rich daddies bought their daughters ponies now they buy them newspaper columns’. For all the babble about ‘diversity’, an ever-narrower class of people dominates journalism, broadcasting, drama and publishing.

2013/12/21

An essay from Quinn Norton (a friend of the late Aaron Swartz, and miscellaneous cyberculture gadfly) about the interplay of money and class:

Money is a sign of poverty. It took a few Scottish sci-fi authors to point this out, but it is the most obvious fact about the concept. Money is a technology for triaging scarcity. It is something you only need when you have to manage a poverty of something else.

When you are poor in America money is chained to shame. You are ashamed that you don't have it, you are ashamed when you do but don't share it with family and friends, you are ashamed when you want it, you are ashamed of what you're willing to do to get it. Like all unchosen masters, you hate it as much as you need it. Money makes you angry, it's what families yell and lie to each other about. Its power is mythologized. One of my most vivid memories of my childhood was my father declaring he didn't have any problems money couldn't solve.Norton posits the thesis that one of the difference between the poor and the middle-class/affluent is that the former don't get to keep their money: not so much because of there being a premium on buying life's necessities when you don't have the signifiers of affluence marking you as one of the Worthy, but because, being poor necessitates relying on communities for support, and one of the prices of that is the obligation to pass any surplus wealth you might have on to those needier than you:

Poor people survive by being part of a community. It can be a family, a neighborhood, or a subculture of alienated teens. Affiliation can take many shapes, and the poor often have more than one. It is implicit and absolute that poor people must support each other. You must make sure those in dire need get what they need even if it costs your savings. This is the fragile safety net that keeps so many people alive and able to function in America, and much of the world. It takes many names, mutual aid, remittance, resource sharing. But if you are making money, you are expected to contribute to keep other people going. To not share your money is to risk not only losing that path of support yourself, but social isolation and shunning.

You're never going to save your way out of being poor unless you're willing to walk away from family and loved ones and let them suffer and sometimes die. Often, the only way you can keep money when you get it is to spend it at once, before the requests for help come in. Making money causes shame, having money causes shame, spending it is no better, and it rules everything you do.

The Middle Class get to keep their money, but in exchange for a social isolation that horrified me when I first encountered it. The truth is, it still horrifies me. The American Dream of a middle class life that the poor, like myself, are supposed to reach for is a nightmare of alienation and loneliness. It takes its physical form in suburbs, and other living arrangements where you can die and be eaten by the cats over a period of months before anyone bothers to check on you.

In families, everything in the middle class pushes people to abandon each other as soon as they have the money to. Children are pushed to education and stable corporate jobs so that they can be shameless — never needing their families in any way. Parents are pushed towards saving for retirement, in either the hope of financially created independence or expectation that their grown children would never abide their presence.

2013/9/25

Apparently Thailand these days is full of homeless European/American blokes; mostly middle-aged, and often alcoholic, they spend their time drinking and sleeping rough on beaches, which is considerably less idyllic than the big-rock-candy-mountain image the description evokes:

Steve, who declined to give his surname over fears that his long-expired visa could land him in jail, said he has spent two years sleeping rough on Jomtien Beach, a 90-minute drive from Bangkok. “I’ve gone 14 days without food before. I lived off just tea and coffee,” he told The Independent. After his marriage of 33 years ended seven years ago, Steve began regular visits to Thailand before setting up permanently in Pattaya, a seaside resort with a sleazy reputation close to Jomtien. “I’m a bit of a sexaholic,” he says, also admitting a fondness for alcohol.

Paul Garrigan, a long-time Thai resident, isn’t surprised by the growing problem of homeless and stranded Westerners. The 44-year-old spent five years “drinking himself to death” in Thailand before giving up alcohol in 2006 and writing a book called Dead Drunk about his ordeal and the expats who have fallen on hard times in the country. He told The Independent: “I’d been living in Saudi Arabia where I worked a nurse but I’ve been an alcoholic since my teens and, after a holiday to Thailand in 2001, I decided I may as well drink myself to death on a beautiful island in Thailand. Like many people I taught English at a school but spent much of my time on islands such as Ko Samui where I could start drinking early in the morning at not be judged.Meanwhile in the US, some homeless people are apparently surviving on Bitcoin; spending their days in public libraries earning the coins by doing vaguely sketchy online work (watching videos to bump up YouTube counters is mentioned; perhaps armies of the destitute to solve CAPTCHAs, artisanally hand-spam blog comments or otherwise laboriously defeat anti-bot countermeasures could make economic sense in today's climate too) and then cashing out through gift card services. Meanwhile, homelessness charities are embracing Bitcoin:

Meanwhile, Sean’s Outpost has opened something it calls BitHOC, the Bitcoin Homeless Outreach Center, a 1200-square-foot facility that doubles as a storage space and homeless shelter. The lease – and some of the food it houses — is paid in bitcoins through a service called Coinbase. For gas and other supplies, Sean’s Outpost taps Gyft, the giftcard app Jesse Angle and his friends use to purchase pizza.(I suspect that the photo of the homeless man “mining Bitcoins” on the park bench on his laptop is mislabelled; wouldn't all the easily minable Bitcoins have been tapped out, with the computational power required to mine any further Bitcoins essentially amount to already having thousands of dollars of high-end graphics cards lying around and using them to heat your house, rather than something one could do with an old battery-operated laptop on a park bench?)

2013/5/6

Recently, celebrity right-wing intellectual Niall Ferguson caused a stir when, during an investors' conference, he implied that economist John Maynard Keynes did not care about the future, on the grounds of being childless and gay. The comments seemed to have been an attempt to attribute Keynes' famous quote, “in the long run, we are all dead”, to an amoral nihilism that comes from neglecting one's duty to reproduce in favour of a decadent hedonism and aestheticism, and thus to tar Keynes' model of government borrowing and economic stimulus, popular amongst the left of the political spectrum but anathema to the neoliberal right, with the brush of this effete, degenerate nihilism:

Another reporter, Tom Kostigen of Financial Advisor, gave a longer account. Kostigen wrote that Ferguson had also made mention of the fact that Keynes had married a ballerina, despite his gay affairs. "Ferguson asked the audience how many children Keynes had. He explained that Keynes had none because he was a homosexual and was married to a ballerina, with whom he likely talked of 'poetry' rather than procreated," Kostigen wrote. He added that the audience at the event went quiet when the remarks were uttered.Ferguson has apologised unreservedly for the remarks once they became public, calling them “stupid and tactless”; chances are that they've served their purpose as a dog whistle, and many of the sorts of people who see “Cultural Marxism” and decadent weakness all around them will agree wholeheartedly.

While Ferguson was rightly excoriated for the anti-gay tone of the remarks, there has been less comment on the other part of his statement, the assertion, still commonly held in many places, that childless people are selfish, amoral nihilists, who refuse to grow up and shoulder their responsibility:

There is, among many otherwise intelligent individuals, an assumption that those of us who make a positive choice to not reproduce are selfish, rootless and have no concern about future generations or the planet. But those who have their own children often forget about the world and just worry about their own ever shrinking one.

I have seen the most passionately committed feminist activists go gaga once they give birth. All the promises such as "I'll still come on that march/go to that conference/burn down that sex shop" disappear when they sprog. All those in my circle with offspring seem to become unhealthily obsessed with their own little world. Principles go out of the window ("I still hate the private education system/healthcare but I am not putting my politics before my children"), and socialising becomes impossible.Big families and the political Right have gone hand-in-hand for a while. Meanwhile, the white-supremacist British National Party, feeling the angry-white-people vote taken away by the less overtly fascistic UKIP, is encouraging its supporters to lie back and think of

"I know, by now you will be giggling over this suggestion. But think about it, nationalists need to buck the trend of 1.8 children per white household. We need to aim between 3 and 4 children each if not more," he writes. "And the bonus is that making babies is fun! So fellow nationalists, less TV and more fun! Let's do our bit for Britain and our race."

Matthew Collins, a former BNP member and now an anti-racism activist, said the post was an attempt by the party to get some attention after its poor election results. "It's tongue in cheek but there is a serious point. Griffin is always going on about being outbred and in the past he has said members need to put away their boots and go and meet women. The problem is that your typical BNP member is a social pariah who is more into pornography than starting a family," he saidA more frightening possibility would be if these people are successfully persuaded to do their duty, especially with the BNP's record on gender relations (they're not in favour of womens' rights; one of their MPs is on record as saying that women should be “struck like a gong”). I wonder in how many suburban culs-de-sac in BNP heartland, aspiring Josef Fritzls are now drawing up plans for soundproofing their basements and making notes on the movements and likely racial purity of fit-looking local shopgirls.

2013/4/17

The International Monetary Fund has, once again, warned Britain's government to ease back on its austerity policy, or risk driving Britain into a triple-dip recession. The government has replied with a statement defending its approach.

Meanwhile, researchers have found serious flaws in an economics paper used to justify austerity policies and the prioritisation of cutting debt at all costs. The paper, Growth In A Time Of Debt, which argues that high public debt stifles economic growth, and which has been a favourite of neoliberals and small-state libertarians, was found to have flaws including selective inclusion of data, unusual weighting of years studied, and a coding flaw in an Excel spreadsheet; when corrected, the data produced does not yield the same conclusions:

This error is needed to get the results they published, and it would go a long way to explaining why it has been impossible for others to replicate these results. If this error turns out to be an actual mistake Reinhart-Rogoff made, well, all I can hope is that future historians note that one of the core empirical points providing the intellectual foundation for the global move to austerity in the early 2010s was based on someone accidentally not updating a row formula in Excel.So, if it does turn out that austerity policies are based on a spreadsheet error, does that mean that we can expect a contrite George Osborne to quickly change course? Of course not; the revelation that austerity is based on junk economics will have no more effect than what we've already known, such that Britain's current public debt is historically quite modest, because austerity never was purely about economic pragmatism, but rather about principle; the principle being “this money does not belong to you”, with the explanation being “because we say so”. Which is why, for example, the government has £10m to give Margaret Thatcher a state funeral in all but name (“we can afford it”), whilst cutting £11.6 from the arts budget, closing public libraries and slashing benefits. The principle is why the government has introduced a “bedroom tax”, cutting the benefits of those deemed to have a spare bedroom, despite the lack of suitably cramped accommodation they could move to (especially in economically depressed areas in the north). There is no economic benefit from this, but it has the moral benefit in the eyes of the Tories and the Daily Mail-reading public of punishing the unworthy poor. And punishing freeloaders is a good in itself, worth doing even if it costs us to do so.

Even if there was no recession, if government coffers were flush with cash, spending money on the public good would be immoral. In Australia, where the economy escaped the recession and is carried aloft on a mining boom, there still is no money for public infrastructure, to the point where recent secondary education reforms had to be funded by massive cuts to the university sector. There is plenty of money, but it belongs not to the little people, but the mining oligarchs, whose sense of property rights does not extend to them rejecting billions of dollars of diesel fuel subsidies paid for by the taxpayer. Needless to say, there is no money for things like modern internet infrastructure or public transport, to say nothing of things like the high-speed railway line between Melbourne and Sydney (the two endpoints of the second busiest passenger air route in the world) for which studies have recently been published. Where there is money left over, it is handed back as tax rebates to middle-class households in outer suburban electorates, where it can do the most good electorally for the government.

The libertarian myth that the economically prudent state is the minimal “nightwatchman state”–enforcing contract law, punishing freeloaders and otherwise keeping its hands off—doesn't bear out in reality, where prior investment and planning are often more prudent than leaving things to the wisdom of the free market. We have seen this in the United States' health care system, where costs are several times higher than in the supposedly inefficient socialised health care systems of socialist Europe (which is not counting externalities, from lower life expectancies and more chronic illnesses to people staying in less than ideal jobs out of fear of losing their health insurance), and in previous attempts to reduce public spending by cutting welfare (at least when the sainted Margaret Thatcher did so in the 1980s). Anyone who has had to commute in a city organised according to laissez-faire let-them-drive-cars principles, at least once it gets beyond a certain level of density, will know that it doesn't work; which is why even neoliberal London and New York spend billions on public transport facilities, which are used with almost Scandinavian egalitarianism by everybody from beggars to bankers. And, in a decade's time, it's not unlikely that the gutting of Britain's social infrastructure will end up costing more, as more people fall through the cracks; some will be picked up by a swelling prison system, as happens across the Atlantic, while others will subsist in dismal conditions, out of sight and out of mind of the people who matter.

2013/4/9

Continuing the Margaret Thatcher Memorial Season on this blog: why the Left gets neoliberalism wrong, by political scientist Corey Robin. It turns out that the thing about rugged individualism is (once one gets beyond the pulp novels of Ayn Rand and Robert Heinlein, not exactly founts of academic rigour) a red herring, and the true atom of the neoliberal world view is traditional, vaguely feudal, hierarchical structures of authority: patriarchial families, and enterprises with owners and chains of fealty:

For all their individualist bluster, libertarians—particularly those market-oriented libertarians who are rightly viewed as the leading theoreticians of neoliberalism—often make the same claim. When these libertarians look out at society, they don’t always see isolated or autonomous individuals; they’re just as likely to see private hierarchies like the family or the workplace, where a father governs his family and an owner his employees. And that, I suspect (though further research is certainly necessary), is what they think of and like about society: that it’s an archipelago of private governments.

What often gets lost in these debates is what I think is the real, or at least a main, thrust of neoliberalism, according to some of its most interesting and important theoreticians (and its actual practice): not to liberate the individual or to deregulate the marketplace, but to shift power from government (or at least those sectors of government like the legislature that make some claim to or pretense of democratic legitimacy; at a later point I plan to talk about Hayek’s brief on behalf of an unelected, unaccountable judiciary, which bears all the trappings of medieval judges applying the common law, similar to the “belated feudalism” of the 19th century American state, so brilliantly analyzed by Karen Orren here) to the private authority of fathers and owners.By this analysis, while neoliberalism may wield the rhetoric of atomised individualism, it is more like a counter-enlightenment of sorts. If civilisation was the process of climbing up from the Hobbesian state of nature, where life is nasty, brutish and short, and establishing structures (such as states, legal systems, and shared infrastructure) that damp some of the wild swings of fortune, neoliberalism would be an attempt to roll back the last few steps of this, the ones that usurped the rightful power of hierarchical structures (be they noble families, private enterprises or churches), spread bits of it to the unworthy serfs, and called that “democracy”.

On a related note, a piece from Lars Trägårdh (a Swedish historian and advisor to Sweden's centre-right—i.e., slightly left of New Labour—government) arguing that an interventionist state is not the opposite of individual freedom but an essential precondition for it:

The linchpin of the Swedish model is an alliance between the state and the individual that contrasts sharply with Anglo-Saxon suspicion of the state and preference for family- and civil society-based solutions to welfare. In Sweden, a high-trust society, the state is viewed more as friend than foe. Indeed, it is welcomed as a liberator from traditional, unequal forms of community, including the family, charities and churches.

At the heart of this social compact lies what I like to call a Swedish theory of love: authentic human relationships are possible only between autonomous and equal individuals. This is, of course, shocking news to many non-Swedes, who believe that interdependency is the very stuff of love.

Be that as it may; in Sweden this ethos informs society as a whole. Despite its traditional image as a collectivist social democracy, comparative data from the World Values Survey suggests that Sweden is the most individualistic society in the world. Individual taxation of spouses has promoted female labour participation; universal daycare makes it possible for all parents – read women – to work; student loans are offered to everyone without means-testing; a strong emphasis on children's rights have given children a more independent status; the elderly do not depend on the goodwill of children.So, by this token, Scandinavian “socialism” would seem to be the most advanced implementation of individual autonomy and human potential yet achieved in the history of civilisation whereas Anglocapitalism, with its ethos of “creative destruction”, is a vaguely Downtonian throwback to feudalism.

2013/3/11

The latest example of the caprice of artificial borders: residents of a coastal village in Kent have found themselves facing high mobile phone bills as their phones latch onto signals from France, across the channel. Then, when their iPhones and Samsung Galaxys inevitably fetch data from the internet, they incur extortionate roaming charges, set at the dawn of time when mobile data abroad was the province of executives with deep expense accounts and left in place because bilking people for checking the email across a border is a nice little earner for the phone companies.

The bay is blocked by the white cliffs from receiving UK signals and people in the village sometimes get connected to the French network depending on atmospheric conditions and the weather. Nigel Wydymus, landlord of the Coastguard pub and restaurant next to the beach, said: "We are a little telecommunications enclave of France here.The phone company, helpfully, advised residents of and visitors to such villages to switch off mobile data roaming:

The spokesman from EE, which covers the T-Mobile and Orange networks, said: "We always recommend our customers switch off roaming while they are in this little pocket of an area to ensure that they are connecting to the correct network, because we cannot control the networks from the other side of the water."This minor absurdity is a result of the distortions of topology caused by a system whose building block is the post-Treaty of Westphalia nation-state, and which, by fiat, sets the distance between any two points within such a state to be a constant. From the mobile phone system's perspective, the distance from Dover to nearby Folkestone is exactly the same as that to London, Glasgow or Belfast, all of which are orders of magnitude nearer than Calais across the Channel. The costs of carrying the data across a system of base stations and trunk cables is part of the settlement of maintaining the legal fiction of the unitary nation-state; the sharp shock of roaming charges is the other side of the coin, a licence for the carriers to make a bit back from the tourists and business travellers, who are either in no position to complain or are used to the data they consume on the go being an expensive premium service. After all, it costs a lot to live in The Future.

Kent isn't the only place where travellers may find themselves virtually (though potentially expensively) abroad; a while ago, I was walking in Cumbria, near Ravenglass, and found myself on the Isle of Man (a separate jurisdiction with its own phone companies and, lucratively, roaming rates).

I wonder how this situation is handled on the continent, where the phones of people living near borders are likely to inadvertently cross them on numerous occasions. Do, say, Dutch phone companies charge roaming Belgians local rates? Do Italians find themselves inadvertently roaming in Switzerland or Croatia? Or do base stations on either side of a border do double-duty, serving both countries' carriers as if they were local?

2013/2/4

The economic difference between London, a global centre of finance, where wealth is conjured into being and every Russian oligarch and Saudi princeling worth his salt has to have a pied à terre, and the rest of Britain is drawn into sharp relief by a recent property value survey:

Research shows that the net value of properties in just 10 London boroughs – Westminster, Kensington & Chelsea, Wandsworth, Barnet, Camden, Richmond, Ealing, Bromley, Hammersmith & Fulham and Lambeth – now outstrips the worth of all the properties in Wales, Northern Ireland and Scotland combined.

The capital’s richest borough, Westminster, with 121,600 dwellings, is worth £95bn – more than twice the value of Edinburgh (pop 500,000) and three times that of England’s sixth most populous city, Bristol.That's one thing one forgets about living in London: that this isn't normal. The high property values (and rents), the billions of pounds poured into public transport, the presence of everything from world-class art exhibitions to lunch options more interesting than a supermarket sandwich: none of this would be here were London not a global city-state of its stature, alongside the Singapores and Dubais of this world.

Of course, the downside of this is that London is considerably less affordable for those who aren't oligarchs, princelings or otherwise loaded.

2013/1/20

Dr. Amelia Fletcher, Chief Economist at the Office of Fair Trade and possibly the world's most high-achieving active indiepop musician, has just been appointed Professor of Competition Policy at the University of East Anglia. This is about three months after her former Talulah Gosh bandmate Elizabeth Price won the Turner Prize.

Professor Fletcher's current band Tender Trap released their most recent album, Ten Songs About Girls last year; it featured in The Null Device's Records of 2012.

2012/1/29

Idea of the day: the Happy Recession; the idea that the internet, through driving prices and costs down, will permanently deflate both prices and wages; the post-internet world, it seems, jams econo:

The most pernicious aspect of Internet entertainment is that it’s so easy to measure and so easy to mass-produce. So the moment something on the Internet gets fun enough to be competitive with the real-world analogue, it starts getting relentlessly improved until it’s vastly superior. World of Warcraft soaks up upwards of forty hours per week from serious fans, who pay about $15 per month for their subscriptions. Few other hobbies can consume so much time at such a low cost.

The web makes it easier to access non-traditional employees at much lower salaries. As we argued in our Demand Media analysis, the real story here is that a stay-at-home mom with a Masters in Journalism can write content that is good enough compared to a typical Madison Avenue copywriter, especially when the rate is $15 per article instead of six figures per year. This disaggregation of writing skill means that companies no longer have to hire good writers in order to write 5% good copy and 95% mediocre work; they can outsource the mediocre stuff and relegate the high-end work to a short-term freelancer.

The web offers cheap social status: In the long term, this may have a bigger effect than the web merely making digitizable products cheaper. Social status games drive a huge amount of economic activity: people strive to get into high-paying, high prestige career tracks, to win promotions and attendant raises, to live in the best neighborhoods and send their kids to the best schools. Few status games lack some kind of economic output—people who play sports well below the professional level still get some job opportunities out of it.One could probably also add a geographical factor to this: in the age of cheap, ubiquitous opportunity, access to economic and cultural opportunities is less dependant on being located in a buzzing metropolis or creative-class hive; after all, if a copywriter or app developer can work from anywhere with creativity, things like music and art scenes (or whatever replaces the post-punk rock'n'roll era construction of the "music scene" in the cultural ecosystem) are centred around blogs rather than physical venues, and one doesn't even need to move to a different place to find like-minded people, there would be less competition for living in more desirable areas, when the price of not doing so no longer includes disconnection from as many opportunities.

2011/12/18

Néojaponisme, the blog of Japanese resident W. David Marx, has a five-part piece on how Japan's economic malaise has changed Japanese pop culture (parts 2, 3, 4, 5), in particular, causing the decline of the mainstream and the rise of the fringe to prominence. The gist of this is that the golden age of Cool Japan is over; as Japanese consumers' spending power declined, mainstream consumers cut back, and cultural markets, such as music, publishing and TV have collapsed, resulting in what some commentators refer to as "the generation who don't consume". with the notable exception of fringe genres catering to marginal subcultures for whom consuming cultural products is not a matter of choice but of identity; these include the otaku (whom Marx sums up as "anti-social “nerds” interested in science fiction, comic books, video games, and sexualized little girls (lolicon)"), the yankii—working-class juvenile delinquents with poor economic and lifestyle prospects—and the gyaru, a female analogue of the yankii, only oriented around romantic fiction and elaborate cosmetics.

The end result is that the otaku and yankii have an almost inelastic demand for their favorite goods. They must consume, no matter the economic or personal financial situation. They may move to cheaper goods, but they will always be buying something. Otherwise they lose their identity. While normal consumers curb consumption in the light of falling wages, the marginal otaku and yankii keep buying. And that means the markets built around these subcultures are relatively stable in size.So while demand in the mainstream has cratered, the culture industry has retooled to servicing these reliable subcultures, with cultural products such as highly sexualised girl groups appealing to older men with schoolgirl fetishes and films with yankii themes. One side effect of this is that the days of Japanese pop culture appealing to hip, affluent consumers abroad may be over:

Most men around the world are not wracked by such deep status insecurity that they want to live in a world where chesty two-dimensional 12 year-old girls grovel at their feet and call them big brother. The average university student in Paris is likely to read Murakami Haruki and may listen to a Japanese DJ but not wear silky long cocktail dresses or fake eyelashes from a brand created by a 23 year-old former divorcee hostess with two kids. Overseas consumers remain affluent, educated, and open to Japanese culture, but Japan’s pop culture complex — by increasingly catering to marginal groups (or ignoring global tastes, which is another problem altogether) — is less likely to create products relevant for them.

2011/4/15

50 years after the Bay of Pigs invasion, the Cuban government is preparing to concede defeat in the struggle for socialism, and unveil radical reforms:

Evidence, as Castro himself said in a recent interview, that "the Cuban model doesn't even work for us any more". Which is why on Saturday the Communist party will inaugurate its first congress in 14 years to cement radical changes to the economy and, intentional or not, to Cuban society.

"The narrative is really Thatcherite," said one senior western diplomat in Havana. "It's all about cutting rights and welfare and putting greater emphasis on personal responsibility and hard work."It'd be ironic if, as Cuba prepares to liberalise its economy and open itself up to investors, the investors came to the Cuban government and advised them to actually keep the infrastructure of totalitarianism in place, because of its usefulness in increasing productivity, controlling unrest and ensuring the integrity of intellectual-property licensing.

2011/2/11

Vanity Fair has a long but interesting article about the Irish financial crisis:

reland’s financial disaster shared some things with Iceland’s. It was created by the sort of men who ignore their wives’ suggestions that maybe they should stop and ask for directions, for instance. But while Icelandic males used foreign money to conquer foreign places—trophy companies in Britain, chunks of Scandinavia—the Irish male used foreign money to conquer Ireland. Left alone in a dark room with a pile of money, the Irish decided what they really wanted to do with it was to buy Ireland. From one another. An Irish economist named Morgan Kelly, whose estimates of Irish bank losses have been the most prescient, made a back-of-the-envelope calculation that puts the losses of all Irish banks at roughly 106 billion euros. (Think $10 trillion.) At the rate money currently flows into the Irish treasury, Irish bank losses alone would absorb every penny of Irish taxes for at least the next three years.

Yet when I arrived, in early November 2010, Irish politics had a frozen-in-time quality to it. In Iceland, the business-friendly conservative party had been quickly tossed out of power, and the women booted the alpha males out of the banks and government. (Iceland’s new prime minister is a lesbian.) In Greece the business-friendly conservative party was also given the heave-ho, and the new government is attempting to create a sense of collective purpose, or at any rate persuade the citizens to quit cheating on their taxes. (The new Greek prime minister is not merely upstanding, but barely Greek.) Ireland was the first European country to watch its entire banking system fail, and yet its business-friendly conservative party, Fianna Fáil (pronounced “Feena Foil”), would remain in office into 2011. There’s been no Tea Party movement, no Glenn Beck, no serious protests of any kind. The most obvious change in the country’s politics has been the role played by foreigners. The Irish government and Irish banks are crawling with American investment bankers and Australian management consultants and faceless Euro-officials, referred to inside the Department of Finance simply as “the Germans.” Walk the streets at night and, through restaurant windows, you see important-looking men in suits, dining alone, studying important-looking papers. In some new and strange way Dublin is now an occupied city: Hanoi, circa 1950. “The problem with Ireland is that you’re not allowed to work with Irish people anymore,” I was told by an Irish property developer, who was finding it difficult to escape the hundreds of millions of euros in debt he owed.

A few months after the spell was broken, the short-term parking-lot attendants at Dublin Airport noticed that their daily take had fallen. The lot appeared full; they couldn’t understand it. Then they noticed the cars never changed. They phoned the Dublin police, who in turn traced the cars to Polish construction workers, who had bought them with money borrowed from Irish banks. The migrant workers had ditched the cars and gone home. Rumor has it that a few months later the Bank of Ireland sent three collectors to Poland to see what they could get back, but they had no luck. The Poles were untraceable: but for their cars in the short-term parking lot, they might never have existed.

2011/1/18

If you're thinking of doing a PhD to advance your career, you may want to reconsider: there is a glut of PhDs in the market and not enough jobs for them, other than postdoctoral work at slave-labour wages:

One thing many PhD students have in common is dissatisfaction. Some describe their work as “slave labour”. Seven-day weeks, ten-hour days, low pay and uncertain prospects are widespread. You know you are a graduate student, goes one quip, when your office is better decorated than your home and you have a favourite flavour of instant noodle. “It isn’t graduate school itself that is discouraging,” says one student, who confesses to rather enjoying the hunt for free pizza. “What’s discouraging is realising the end point has been yanked out of reach.”

Whining PhD students are nothing new, but there seem to be genuine problems with the system that produces research doctorates (the practical “professional doctorates” in fields such as law, business and medicine have a more obvious value). There is an oversupply of PhDs. Although a doctorate is designed as training for a job in academia, the number of PhD positions is unrelated to the number of job openings. Meanwhile, business leaders complain about shortages of high-level skills, suggesting PhDs are not teaching the right things. The fiercest critics compare research doctorates to Ponzi or pyramid schemes.As a result, the traditional bargain (crummy pay now for an academic career later) no longer holds, and postdocs are starting to see themselves not as apprentices on the first step to something better but as disposable cheap labour. (In Canada, apparently 80% of postdocs earn no more than the salary of a construction worker.) This has led to a new development: the rise of trade unions of PhD-accredited teaching staff.

As far as non-academic careers go, the picture isn't much brighter. Having a PhD no longer gets one a salary premium over having a mere Master's. (In some areas, such as engineering and technology, a PhD actually gets you less than a Master's. Meanwhile, the functions of having a PhD (i.e., advanced knowledge potentially applicable to a field) have been taken over by more specialised, market-oriented courses:

Dr Schwartz, the New York physicist, says the skills learned in the course of a PhD can be readily acquired through much shorter courses. Thirty years ago, he says, Wall Street firms realised that some physicists could work out differential equations and recruited them to become “quants”, analysts and traders. Today several short courses offer the advanced maths useful for finance. “A PhD physicist with one course on differential equations is not competitive,” says Dr Schwartz.I imagine this is part of the ongoing theme of the entire education infrastructure of the current world, having developed largely from the Middle Ages onward, not keeping pace well with technologically-driven social and economic change. Chances are that, over the next few decades, the assumptions of how education works and what functions it fulfils will have to be looked at anew on all levels.

2010/11/16

High demand for cocaine in Europe + high prices due to drug prohibition + global trade downturn resulting in glut of cheap cargo jets + Venezuela not cooperating with the War On Drugs = drug cartels buying jumbo jets, packing them with cocaine, flying them to Europe and then torching them, because it makes economic sense:

Fuel and pilots were paid for through wire transfers, suitcases filled with cash and, in one case, a bag containing €260,000 (£220,000) left at a hotel bar. The gang hired a Russian crew to move a newly acquired plane from Moldova to Romania, and then to Guinea.

The gang had access to a private airfield in Guinea, was considering buying its own airport and had sent a team to explore whether it could send direct flights from Bolivia to West Africa, Valencia Arbelaez said in recorded conversations.

2010/10/24

Economist Robin Hanson presents a sustainability-based argument for derivative music:

Each new song sits somewhere in a range of originality, from very original to very derivative. The more new original songs are developed and marketed, the harder it gets to develop and market new songs that will be seen as relatively original. Song writers then become more tempted to develop and market recycled versions of old songs. As the supply of original songs is slowly exhausted, the music industry slowly changes its focus from original to derivative songs. Since original music cannot last forever, we face a “sustainability” question regarding whether we are using up the supply of original music too quickly, too slowly, or just right.So when you next see another ploddingly dull lad-rock band rehashing the Beatles or Joy Division once more, without feeling, or hear another cringeworthily trite song about being or not being in love, or roll your eyes at a hack lyricist rhyming "girl" with "world", perhaps consider for a moment that, rather than polluting the world with mediocre pap, they're wisely rationing the finite supply of original musical ideas by not using any. Meanwhile, if the space of original musical ideas is in danger of depletion, the musical snobs who turn up their noses at Robbie Williams or Oasis and listen exclusively to post-tropicalia glitch-hop mashups and avant-garde experimentalism are not so much laudably adventurous spirits as the cultural equivalent of the conspicuously consuming douchebags who drive Hummers and buy endangered animal products.

That is assuming that the space of new musical ideas is finite, of course, and that once it is depleted, there will be nowhere left to go; once every possible verse-chorus-verse song in a blues scale has been written, for example, that humanity will be doomed to listen to songs they've all heard before, rather than, for example, changing the rules of what constitutes (popular) music.

2010/9/16

An Italian company has developed a new, ultra-compact airline seat for making economy class even more economical. Called the Skyrider, it takes only 23 inches, and involves the passenger sitting astride a saddle.

One could imagine penny-pinching airlines like Ryanair tearing out all their existing seats and replacing them with these, knowing that their clientele don't mind an hour or two of discomfort in return for getting to Ibiza or wherever for less than the train fare to the airport, though, as pointed out here, an entire jet full of these won't be possible for regulatory reasons. (Even if the total weight of the passengers sardined into it doesn't exceed the maximum carrying weight, the requirement that the aircraft can be evacuated in 90 seconds puts an upper limit on the number of passengers per exit.) The seats, it seems, aren't so much intended for budget carriers as for mixed carriers, allowing them to put in a tier below economy class, moving their lowest fares to this tier and raising the prices of their old cattle-class seats. Consequently, airlines, pressed by fuel prices and fare wars, will become slightly less unprofitable, and the flying experience will become that little bit shittier.

2010/8/10

Over the past few decades, the market value of recorded music has been declining, as music has gotten easier to make and distribute, to the point where there is a flood of music vying for one's attention, and the challenge is not finding it but sorting the worthwhile stuff from the dross and filler. Of course, this sucks if you're a musician trying to be heard, as you're competing for the limited attention of your audience with millions of others.

The latest outcome of this commodification: a British band calling itself The Reclusive Barclay Brothers has paid 100 people £27 to listen to their song, a jaunty little number titled We Could Be Lonely Together.

2010/6/29

In Paris, fare evaders on the Métro have organised into outlaw insurance societies. The mutuelles des fraudeurs take a monthly fee of somewhere around 7 euros, and in turn offer to pay the fraudsters' fines, should they get caught. They also compile databases of fare-evading tips and encourage those who would otherwise be too timid.

Back in 2001 or so, he and a group of fellow travelers, in both the literal and metaphorical senses, formed the Network for the Abolition of Paid Transport, "the beginning of our struggle," Gildas calls it. The group's initials in French mimic those of the agency that runs the Metro and buses, and to the agency's logo, which looks like the outline of a face, abolitionists added a raised fist.The mutuelles claim justification, oddly enough, from left-wing ideology. Defrauding the Métro of ticket revenue is not an act of individual greed, you see, but a collective blow against capitalism. It's true that the Paris Métro may not be run for profit as public transport systems in the Anglosphere tend to be, but such trivialities are of no matter when issues of sweeping ideology are at stake. The Métro, they contend, should be free to ride, with the €8bn or so it costs to run each year being paid for by expropriating the rich. (What they'll do when the rich have all been expropriated, or have fled to Russia or Dubai or a floating Galtian utopia on the high seas, they do not explain; nor do they explain how they'll prevent a free, ungated public transport system turning into an expensive homeless shelter, driving away those passengers who have a choice of where to go.) No, they're striking a blow against the fascist regime that is the RATP, and helping to bring forward the advent of the Another World that Is Possible. And, quite probably, breaking the law; insurance against penalties for unlawful acts is generally frowned upon.

(It occurred to me that, were something like the mutuelles des fraudeurs to arise in the English-speaking world, it'd be couched in the language of free-market libertarianism rather than macaronic pseudo-socialism. Rather than attempting to sell a nebulous collective solidarity, it'd speak out to the individual in the language of self-improvement and competition, imploring them to be a winner and not a loser (like the chumps who pay full fare), and would defend itself as the invisible hand of the free market providing a service and/or striking a blow against socialism.)

2010/5/4

As Greece's economic problems raise fears of a possible collapse of the Euro, or even the end of the ambitious single currency, financial commentators are already publishing advice on how to profit from it:

Two: Buy the US dollar. Sure, it has its own problems. The US budget and trade deficits are huge. Wall Street is under attack from populist, crusading politicians. Its share of the global economy is in long-term decline. But with the euro gone, it would be the only serious reserve currency - at least until China decides to take on that role. Without any competition, the dollar would only strengthen.

Seven: Buy airlines. For a few years, the “new drachma” would make the Iraqi dinar look like a haven of stability. It would plunge, and wealthy northern Europeans would be taking three or four holidays a year on Greek islands. That would be great for the companies that fly tourists there. Add in the weakness of the new Portuguese escudo, Spanish peseta and Italian lira, and the guys at Airbus will be working nightshifts to keep up with the demand for new planes to get everyone to the beaches.Other advice is to buy into German bonds, the pound (though what about other non-Eurozone currencies such as the various Scandinavian ones?) and Italian shares (Italy's apparently likely to prosper in a post-Euro world), whilst avoiding Spanish banking shares and anything to do with Belgium (in a post-Euro world, it's merely "a small place where you can buy some nice chocolate and change trains").

2010/4/29

An article in The Guardian (which, incidentally, has a paid online dating site) claims that online dating is now socially acceptable, to the point where people who met on dating sites no longer lie about having met in a pub.

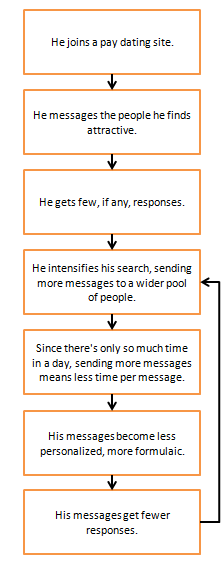

Meanwhile, OKCupid's excellent stats blog claims that paid-for online dating is a losing proposition, and puts forward a theory backed with numbers on why it's so. Behold: the Desperation Feedback Loop:

The Desperation Feedback Loop is exacerbated by the economics of paid-for dating sites, 93% of whose profiles (by OKCupid's reckoning) are inactive and which make higher profits by presenting these inactive profiles to customers. (Doing so keeps subscribers signed up longer.) Meanwhile, the punters flirting into the void get no replies, and slump into the feedback loop of sending out more, lower-quality, messages. Meanwhile, the recipients of these messages, confronted with a higher signal-to-noise ratio, stop reading their messages, further reducing the number of active profiles.

Of course, it's in OKCupid's interests to tell you this because they're an unpaid dating site who compete with the paid dating sites. The implication is that their model works better.

2010/4/20

The decline of physical media continues, as one of Melbourne's larger and more long-lived independent labels abandons the CD format; from now on, Rubber Records (home to Underground Lovers, among other acts) won't actually sell records but only digital downloads.

“Physical retail distribution is dictated by a business model that no longer works for either the customer, the artist or the label,” Rubber MD David Vodicka said in a statement. “It’s also anti-competitive. We can’t sell-in direct to the biggest national retailer JB Hi Fi, we have to go through a third party distributor with an account. Distributors take a minimum cut of 25 percent, and we have to pass that onto the consumer. There’s no point in engaging in this model as it currently stands. We’ll consider it in the future, but only if it works for us."A final liquidation of stock is planned for 15 May.

2010/4/15

During the Cold War, the Soviet Union established a system of secret science cities, or "naukograds" in Russian. These cities were closed off from the rest of the USSR and identified only by numbered names; in them, elite scientists lived in relative luxury and worked on secret projects, while armed guards prevented anyone without authorisation from getting in or out. One could think of the naukograds as a Soviet-era cross between the Google campus and The Village.

Of course, developing nuclear bombs or putting a live dog into orbit is one thing, and competing in the technological marketplace is another, and Russia hasn't been punching its weight. While America has Apple, Google, Microsoft, Amazon and such and Japan and South Korea supply the world with cameras, LCD screens and memory chips, Russia has a gimmicky LED keyboard and LiveJournal (a US-based, American-built site which is Russian-owned). The post-Soviet economy is worryingly dependent on exports of natural resources such as oil and gas, and, while Russia does produce good scientists and engineers, worryingly many of them end up in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Now, seemingly chagrined by the lack of hype about the latest must-have Russian smartphone in the pages of Engadget, the Russian government has decided to do something about it and build a modern, web-age version of the naukograd, with less secrecy and more bean bags and sushi bars; an attempt to replicate the success of Silicon Valley by fiat, stop the brain drain and boost the Russian technology industry. Of course, there is some dispute over how to actually go about doing this:

In the midst of the oil boom, Russian officials suggested luring back Russian talent by building a gated residential community outside Moscow, designed to look like an American suburb. What is it about life in Palo Alto, they seemed to be asking, that we cannot duplicate in oil-rich Russia?

“In California, the climate is beautiful and they don’t have the ridiculous problems of Russia,” Mr. Shtorkh said. To compete, he said, Russia will form a place apart for scientists. “They should be isolated from our reality,” he added.

HIGH-TECH entrepreneurs who stayed in Russia are more skeptical. Yevgeny Kaspersky, founder of the Kaspersky Lab, an antivirus company, says that he is pulling for the site to succeed but that the government should confine its role to offering tax breaks and infrastructure.A site has been chosen for the first new naukograd, though a name has not yet been decided. Until one is, it is variously referred to, unofficially, as Cupertino-2, Innograd and iGorod.

2010/3/18

Scifi author and blogger Charlie Stross has written a five-part series on how the publishing industry actually works: The structure of the publishing industry, how books are made from manuscripts, a dissection of a book contract (with digressions on the implications of clauses, and why it's in an author's interests to get an agent), the logistics and economics of territories and translations, an exposition of the economic forces responsible for books being the length they are, with speculation on possible future trends, and a piece on who comes up with book titles, blurbs and cover artwork (hint: it's not the author). As with all of Charlie's writing, it's keenly insightful and highly readable.

2010/2/7

An economist from Santa Fe, New Mexico, is questioning the neoliberal economic assumption that economic inequality is the flipside of efficiency. Professor Samuel Bowles, who became interested in the question of inequality at the time of Martin Luther King, claims that economic inequality causes inefficiency, by locking up productive labour as "guard labour", required to protect the wealth of the haves and keep the have-nots compliant and productive:

In a 2007 paper on the subject, he and co-author Arjun Jayadev, an assistant professor at the University of Massachusetts, make an astonishing claim: Roughly 1 in 4 Americans is employed to keep fellow citizens in line and protect private wealth from would-be Robin Hoods.

The job descriptions of guard labor range from “imposing work discipline”—think of the corporate IT spies who keep desk jockeys from slacking off online—to enforcing laws, like the officers in the Santa Fe Police Department paddy wagon parked outside of Walmart.

The greater the inequalities in a society, the more guard labor it requires, Bowles finds. This holds true among US states, with relatively unequal states like New Mexico employing a greater share of guard labor than relatively egalitarian states like Wisconsin.While some guard labour will exist even in the most egalitarian of societies, too much guard labour sustains "illegitimate inequalities", and unproductively locks up units of labour which could, in a more equal society, be employed more productively. And an excess of guard labour also continues inequality, by allowing the creation of a "working poor" compelled by economic necessity to accept unfavourable working conditions, a segment of the workforce it is difficult to elevate oneself (or one's children) out of.

2009/10/15

Steven Levitt and Stephen Dubner, the authors of Freakonomics, have a sequel coming out next week; titled, naturally, Superfreakonomics, it looks like the same winning blend of insights, economic detective stories and at times glib reductionism:

Thus in the new book we learn, for example, that more deaths are caused per mile, in America at least, from drunk walking than drunk driving – so when you drive to a party and get plastered, it's not necessarily a wise decision to leave the car and walk home. We discover that female emergency-room doctors are slightly better at keeping their patients alive than male ones, and that Hezbollah suicide bombers, far from being the poorest of the poor, with nothing to lose, tend to be wealthier and better-educated than the average Lebanese person. There's an artful takedown of the fashionable "locavore" movement: transportation, Levitt and Dubner argue, accounts for such a small part of food's carbon footprint that buying all-local can make matters worse, because small farms use energy less efficiently than big ones.

Their mission to explain the world through numbers alone can give Superfreakonomics an oddly detached feel: major social issues are addressed, then instantly reduced to a statistical parlour game. An interesting section on the transactions between pimps and prostitutes, for example, shows that working with a pimp confers great financial advantages: they're much more helpful to prostitutes than estate agents are to house-sellers, for a start. But it neglects to consider the notion that there might, just possibly, be some negative aspects to the pimp-prostitute relationship. (The authors, apparently aware that they have made it look as if selling sex is the business plan to beat all others, add a helpful clarification: "Certainly, prostitution isn't for every woman.")

2009/5/28

To figure out the current state and direction of the global economy, economists are turning to somewhat unusual indicators, such as the membership of extramarital infidelity websites and the price of prostitution in Latvia:

The Web site crunched its traffic and membership numbers and found that there was a big increase in both when there was a turning point in the FTSE-100 index, which measures the leading companies listed in London. When the market collapses, people plot affairs. And when the bulls rage, the same thing happens. When it is trading sideways, they stick with their partners.

“It has to do with people’s confidence levels,” says Rosie Freeman-Jones, a spokeswoman for the site. “When the markets are up, they think they can have an affair because they feel they can get away with anything. When the market hits the bottom, they are looking for a way to relieve the pressure.”And here is more information on the prostitution index, and why prostitution prices make a good economic indicator.

Anyway the problem is that most industries have contractual arrangements which fix prices. Wages are very hard to flex downwards. Rents are fixed over sustained periods and the like. All of this means that people go bust rather than reduce prices – simply because prices are sticky.

Well – most prices. The contractual terms of prostitution are short (an hour, a night) and entry to the industry is unconstrained. That means that the prices are very flexible. Extraordinarily flexible.

2009/4/20

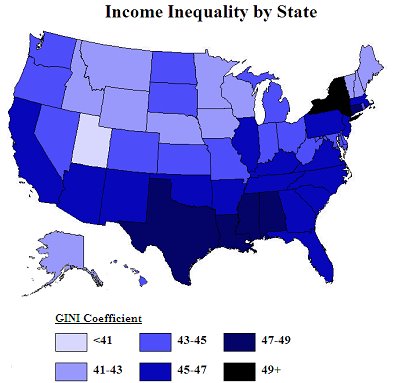

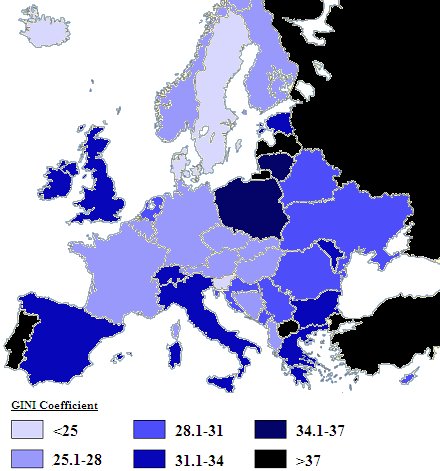

The Map Scroll blog has a map of the Gini coefficients of all the US states, and another one of Europe.

The Gini coefficient is a number from 0 to 1 representing the equality or inequality of income distribution in an economy; 0 is theoretical absolute equality, and 1 is one person having everything and everyone going without. In practice, it varies from about 0.2 to about 0.7.