The Null Device

Posts matching tags 'culture'

2020/4/28

My name is Andrew, and until now, I have never watched Twin Peaks.

I had seen, and enjoyed, various of David Lynch's films (Lost Highway in particular made an impact on me at the time with its uneasy dreamlike vision). Twin Peaks had been on television, of which I didn't watch much at the time (the novelty of the internet, in its text-based, pre-web version, had consumed my spare attention). I, of course, couldn't help but be aware of it: the media hype, the Bart Simpson Killed Laura Palmer T-shirts every attention-seeker was wearing. At the time it was easy enough to dismiss it prematurely as just another dumb TV show; something people who watch TV will witter about for the next few weeks and then forget, moving onto the next mass spectacle. (This was about a generation before the idea of Quality TV came around, when episodic TV shows were perceived, mostly accurately, as low-rent boob-bait, something acknowledged in Twin Peaks with its own references to lurid telenovela tropes.) In the years that followed, its influence kept coming up repeatedly in ways that generic dumb TV shows don't. I had friends who made art referencing it, made pilgrimages to the locations, travelled to conventions and got selfies with actors from it, and who sought out David Lynch's pop-up bar in Paris; such fandom doesn't generally happen for, say, Growing Pains or Melrose Place (to choose two names at random).

I wasn't completely truthful when I said I had never watched Twin Peaks. Many years ago, I got a copy (I can't remember where: a set of DVDs borrowed in Melbourne in the late 90s, or some .avi files copied from a friend in California in the late 00s, or a DVD box set buried in a box in a storage locker in Melbourne) and watched the pilot and the second episode. My impression was: this is some kind of greaser hell, a tough, brutal world ruled by the inevitability of violence, and the logic of violence as honour, like Viking-age sagas crossed with Nick Cave murder ballads, with a 50s rock'n'roll soundtrack. It didn't help that among the first characters I saw who were doing something other than merely reacting in shock were a reptilian psychopath whose psychological and physical abuse of his (young, pretty, terrified) wife was probably the least of his crimes, and a greaser hoodlum, whose propensity for impulsive violence had a boys-will-be-boys logic to it, and who ended the episode literally howling like a wolf to intimidate another guy. The phrase “toxic masculinity” was not common currency yet, but it would have described a fundamental element of this world, along with perhaps the great American founding myth of righteous violence. This bleak worldview did not, at the time, compel me to prioritise watching the third episode immediately; I had other things to do, and soon the whole series ended up receding further into the backlog of unwatched TV; to be watched when I found the time. The years passed, and I absorbed bits of it by osmosis, much as one does with, say, Star Trek or Game Of Thrones or Lost; sort of knowing what the Black Lodge is in the way that I sort of know what the Red Wedding or Darmok And Jalad refer to. Over the years, more and more of it slipped into the periphery of my world: the iconic red curtains and zigzag flooring of the Black Lodge appearing in various places, music influenced by the Cocteauvian doo-wop of the soundtrack; I went to a burlesque night in East London which turned out to be Twin Peaks-themed, and undoubtedly missed most of the references; a year or two later, I instantly recognised a (sublime) shoegaze version of the Twin Peaks theme played at a gig at the Union Chapel in Islington.

And so, the .avi files sat on a succession of hard drives (and were more recently supplanted by a BluRay box set, the product of a wish-list-mediated long-distance Christmas), waiting for me to get around to watching them. I copied them to my iPad once, with the view of catching up whilst travelling, but never did: the sheer wall of 29 episodes acted as a psychological barrier: do I have the time to commit to this now? Then, in 2017, came the return: a third series, set (more or less) in the same universe with the same characters. On one hand, the pressure to finally bite the bullet and catch up increased: half the people I knew were talking about it, their talk in a code I half understood, and this would only intensify; on the other hand, the wall of canonical content would only grow steeper and more imposing. The season came and went, friends tweeted about it and started podcasts, but I stayed behind, unable to find the time to catch up on the originals.

But then, a year and a bit after I moved to Sweden, The Covfefe hit. Suddenly I was working from home and not going out; all events and travel plans were up in the air, indefinitely. I looked towards my stack of unwatched video, picked the Twin Peaks pilot from it, and rewatched it to refresh my memory. The following day, I learned that I had done so on the 30th anniversary of its original airing. And so, over the next few weeks, I would rewatch all 29 episodes of the original seasons; starting with one a night, though culminating at four. Last night, I watched the last one,

My impressions were: the mood does get less oppressive from the third episode onwards: Agent Cooper, the idealistic, mystically-inclined FBI agent sent in to solve the murder, does bring a sense of wonder, and also a sense of unreality (the idea that an FBI agent would use dream divination to attempt to solve a case, and that the bureau would back him up on this rather than, say, confining him to the basement where they keep their crank file, serves to break the bonds to realism). The cavalcade of oddities (some, but not all, connected to Cooper) pushes this along further, somewhere between magic realism and the Weird America of a Werner Herzog documentary, whilst keeping things moving along. Meanwhile, the TV format keeps it partially anchored to the tropes of 1980s TV drama, though sometimes testing them to breaking point (case in point, a mynah bird being material witness to the murder, and ending up assassinated). As many others have pointed out, the show loses a lot of momentum in the second season; some of the small-town quirkiness bloats out into a tangle of subplots, which feel like filler (the one about Nadine's superhuman strength/age regression and the one about the paternity of Lucy's child, to name two). The show did pick up towards the end, though by then veering into comic-book territory. What had started with an all too brutally realistic act of evil ended with a luridly fantastic cat-and-mouse game against a ludicrously well-resourced supervillain. (And while Cooper's ex-partner turned megalomaniacal psycho-killer Windom Earle was the most obvious example of a comic-book villain there, both Leland Palmer and Benjamin Horne developed the air of villains from the 1960s Batman series about their characterisation.) The series did end with a stack of cliffhangers, inconveniently enough as there was not a third season within its timeline.

The world of Twin Peaks seemed curiously anachronistic, as if stuck in a Long 1950s going well into 1989; the ghosts of Elvis and James Dean cast a long shadow here, particularly on the younger generation with whose parents these icons would have resonated. (The idea of a soulful, brooding, leather-jacketed teenage rebel riding a Harley would probably have seemed anachronistic in 1990, let alone now.) The adult characters also have a midcentury aura about them: a clubbable whisky-and-golf masculinity that can respectably paper over all manner of discreet vices.

There are some things which didn't age well. For one, Twin Peaks is very white, and it's well into the second season before one sees an African-American face. Which makes one wonder: where did all the black people go? Women characters are often handled in a less than even-handed way; Lynch does seem to like fridging his women to generate jeopardy and tension, and while there are some well-written female characters with agency (one could imagine, in a world where this was more successful, Audrey Horne getting her own spin-off series; you know that she had adventures), many seem to exist merely as bait of one kind or another, squirming or shimmying on the end of a plot device, femmes fatales or angelic victims. Gender-identity diversity fares slightly better; there’s one cross-dressing character — played by an unknown David Duchovny, still a year or two from his own fame as an idealistic, esoterically obsessed FBI agent—though s/he feels more one of a kind with the giants, dwarfs and one-armed men who occupy Lynch’s phantasmagoria than a nuanced sketch of LGBTQ experience. Still, for 1991, a cross-dressing character who is neither a sick villain nor a murder victim was probably quite progressive.

Finally watching the original series both was and wasn't revelatory; much of what could be easily described about it was not a surprise, as it had saturated the cultural environment. What was surprising were the little details: the combination of boy-scout earnestness and profound psychedelic oddness that was its implausible protagonist, the sometime dream-logic governing the actions of the characters (would anyone in real life have acted as they did?). Also, the change in proportions between the actual series and its long afterimage; it was hard to believe that the iconic Black Lodge, the Chapel Perilous of the Twin Peaks universe whose decor inspired a million imitations and homages, only appeared in the final 10 minutes or so of the final episode and a short dream sequence in the first one.

The final takeaway was noticing ripples of Twin Peaks in the world that followed. Some are more obvious than others. One can see elements of the series, distilled to a much higher purity, in the films of Wes Anderson, for example, and what is Donnie Darko if not a jejune student-project attempt at Lynchianism reduced to Hot Topic-era adolescent angst? There was, of course, also the X Files, which aimed at similar territory though in a more literally grounded way, taking the questions of American paranoiac folklore — what if UFOs and/or Bigfoot are real? what if the government is covering them up? — at face value rather than as emanations of a Jungian collective unconscious, and one could probably make a case for Northern Exposure as a Twin Peaks for normies. Outside of the media, the goths and twee-pop kids took a lot from Twin Peaks; more than one scowling darkling in the industrial, goth or metal scene must have channelled the aforementioned reptilian psychopath, Leo Johnson, in an attempt to look grim and ominous; on the other side, the phrase “the owls are not what they seem” gradually lost its sublime terror and joined the iconography of Etsy-era twee, cross-stitched and hanging in Instagrammable flats where Neutral Milk Hotel vinyl spins on a faux-vintage Crosley.

There are more tenuous connections one could grasp at: might the millennial tendency for tarot and astrology owe anything to Agent Cooper's unorthodox methods? Is there a bit of the Black Lodge in the glitches-and-classical-statuary aesthetic of vaporwave? One memorable semi-recent example is a video by the Icelandic artist Ragnar Kjartansson, which has him crooning the line “sorrow conquers happiness” for several hours, accompanied by an orchestra, and standing in front of a red curtain, as if in a corner of the Black Lodge.

Anyway, those are my observations, only overdue by a couple of decades. At some point I'll get around to watching the new series, whose DVDs are sitting in my living room.

2018/8/31

The Australian government has denied a visa to US whistleblower Chelsea Manning, who was due to speak at the Sydney Opera House, on grounds of character. Civil libertarian groups are, of course, lobbying strenuously for this decision to be reversed, though, inevitably, their pleas will fall on deaf ears. Indeed, there never was a prospect of Manning being allowed into Australia, and anybody who thinks that she might have been does not understand Australia.

Fundamentally, Australia is neither a US-style republic nor a European liberal democracy. Instead, it is the outgrowth of a set of penal colonies and military outposts of a maritime empire, founded on administrative doctrines of such. Its system is not a classically liberal social contract, nor a pretence towards a modern take on the Athenian agora, but books of rules drafted in an office off Pall Mall in London for the maintenance of discipline and smooth running of such a far-flung and potentially fractious enterprise. The colonies were eventually amalgamated into a federal nation, with responsibilities devolved, in due time, from London, and decorated with the trappings of 20th-century liberal democracy, but tradition is a hardy thing, and in many cases, the modern, liberal Australia only goes so deep. Australia, for example, has no equivalent of the US Bill of Rights or the EU Convention on Human Rights; the only formal right that Australians have is that of not having a specific denomination of Christianity imposed as an established state church.

Of course, Australia is not North Korea or even China; informally, there is a generous, if conditional, system, known as the law of Mateship. If you fall under the aegis of Mateship, while you have no formal, official rights enshrined in statutes, you can have faith that the all-powerful authorities will generaly let you be, unless you're seen as some kind of ratbag. How much of a ratbag you have to be to incur the unfriendly attention of the authorities depends on a lot of things, including your skin colour, sex, ethnicity, and whether you fall into any categories of potential troublemakers (which, these days, include Muslims, those easily mistaken for Muslims, brown people in general and transgressors against gender norms). Hence a straight white bloke can, in many cases, get away with all sorts of mischief up to and including advocating (though, of course, not actually carrying out) Communist revolution, whereas if you're, for example, a brown-skinned Muslim, merely having and expressing opinions crosses the line. (A straight white sheila, meanwhile, has most of the privileges of a straight white bloke, unless she complains about sexist banter or becomes Prime Minister or something.) The flipside of the doctrine of Mateship is a ritualised, performative anti-authoritarianism: Australia celebrates outlaw folk heroes from Ned Kelly to Chopper Read (though only if they embody a sort of rough-hewn, stoic masculinity), and, when the time came to replace God Save The Queen as national anthem, came close to choosing a ballad about a sheep thief.

The Law of Mateship is a sort of Australian parallel of Scandinavia's Law of Jante: informal, not actually codified anywhere, and yet of powerful importance, its spirit moving through the society's formal structures, animating its discretionary decisions. Essentially, Mateship is a border; it divides “People Like Us”, who are party to its social contract and entitled to its boons, and the rest of the world, and once you're inside the border, you're in. A recent example is the case of Boofhead, a filthy, rancidly smelly dog whose owner was denied the right to bring it with him into a RSL club; a judge ruled that the club had unlawfully discriminated, and awarded $16,000 in damages. It's tempting to wonder whether a dog by any other name would have been considered in equally good odour by the law, or whether Boofhead's stereotypically Aussie name swung it, but the judge's decision, though not phrased in these words, states clearly that Boofhead is a Mate, and entitled to the protection of the customary rules of Mateship. One of the implications of this is that he has vastly more rights than, say, the asylum seekers on Nauru, imprisoned in the darkness outside of Mateship's border. (Which suggests that perhaps one activist tactic to help these refugees may be to give them quintessentially Aussie nicknames, such as Davo, Shazza and Chook.)

In any case, Chelsea Manning falls outside the boundaries of Mateship sufficiently to be banned from the country under its strict security regime, for two reasons, one official and one unofficial. Officially, Manning is still a convicted criminal against her country, albeit one whose sentence was commuted by Presidential discretion. (She has announced an intention to appeal her conviction, though it has not, to date, been overturned.) Australia has a long-running conservative government, and one which has recently jettisoned an ineffectual centrist leader and lurched further rightward, giving it a simpatico with the Trump administration, not in spite of its sublime awfulness but because of it. Though while this counts as a factor in the decision, it is probably not the deciding factor; I'm not sure that, for example, a Gillard Labor government would have decided otherwise; or, indeed, that any government other than the Whitlam administration would have let Manning in. Informally, Manning being transgender probably does not help her case in a country where the old, rough-and-ready norms of Australian masculinity are digging in for a long siege and attaching themselves to the Murdochian right-wing culture war whose paroxysms often pass for civic discourse, thus being the Wrong Kind Of Ratbag to be privy to Australia's performative anti-authoritarianism.

2018/7/8

So yesterday, England beat Sweden in the world cup, securing their first place in a final in decades, and setting off riotous celebrations. Some football fans, filled with the euphoria of the moment, trashed an IKEA in London, terrorising staff and customers. Others just blocked off streets and jumped on trapped cars.

It’s tempting to see this match, and its aftermath, as the latest flare-up of the Second English Civil War, this time not between the Cavaliers and Roundheads but the Gammons and Snowflakes, and on a broader scale, a Right-vs.-Left grudge match of two fundamentally different world-views of our time. On one hand, England: the bad-boy buccaneers of Brexitland. On the other hand, Sweden, the very symbolic epitome of European liberalism as most unacceptable to the Gammon majority who see themselves as custodians of England’s values, not to mention their fellow travellers in red-state, red-cap America. England may hate the Germans the most, and have hated the French for the longest, but the Swedes are the most egregiously antithetical to the harsh, robust values of the contemporary middle-England whose voice is the Daily Mail. Everything that paper rails against—gender-neutral parenting, multiculturalism, human rights, high taxes spent on the unworthy—is supposedly rampant in Sweden, and if you listen to right-wing older relatives, you will learn that the country is a bankrupt wasteland (due to the inevitable consequences of socialism) and/or an ISIS rape camp.

Sweden is lagom, everything in moderation, with a residual Jante Law stigma against putting oneself above others giving rise to an innate egalitarian tendency. In English, however, it is said that equality is the opposite of quality. We revel in excess. We’re a meritocracy of luxury flats, kept empty as investment units, towering over streets full of hungry, undeserving tramps; a land of teachers and nurses share-housing well into their 40s, and buy-to-let landlords building their well-earned empires, unmolested by redistributive taxation. We’re a nation of hard-working taxpayers who’ve had a gutful of uppity minorities asking to be treated with unearned respect. We're Terry Gilliam jealous of the privileges of imaginary black lesbians, and Morrissey spouting off about Those People. In England, a hedge-fund manager is literally worth thousands of paramedics. And where Sweden believes in universal human rights, inalienable dignity every person is, by definition, entitled to, England, however, divides humans into two camps: “deserving” and “scum”, with the latter to be treated punitively lest they get ideas above their station.

All over the streets outside pubs, mobs of men with St. George flags celebrate jubilantly, blocking traffic and chicken-dancing on the roofs of trapped cars; it's a big boffo day out, like everyone's best mate's stag do. The police come some twenty minutes later and move them on, in their own good time; they’re good lads, just a little overexcited. Hours later, and packs of blokes walk the streets, bellowing out ugly chants about German bombers. We are England, they seem to chant: the English, the English-speaking world, riding the ascending surge of the age. Donald Trump, the commander-in-chief of the English-speaking peoples, is ultimately our leader. Boris Johnson is our shit Churchill for this shit age. Human rights, social justice, Political Correctness, Cultural Marxism, the Frogs and Krauts and all their vino-drinking, garlic-eating chums, all lie vanquished under our boots. And we’re just getting started.

All over the streets outside pubs, mobs of men with St. George flags celebrate jubilantly, blocking traffic and chicken-dancing on the roofs of trapped cars; it's a big boffo day out, like everyone's best mate's stag do. The police come some twenty minutes later and move them on, in their own good time; they’re good lads, just a little overexcited. Hours later, and packs of blokes walk the streets, bellowing out ugly chants about German bombers. We are England, they seem to chant: the English, the English-speaking world, riding the ascending surge of the age. Donald Trump, the commander-in-chief of the English-speaking peoples, is ultimately our leader. Boris Johnson is our shit Churchill for this shit age. Human rights, social justice, Political Correctness, Cultural Marxism, the Frogs and Krauts and all their vino-drinking, garlic-eating chums, all lie vanquished under our boots. And we’re just getting started.

The word on the street here is that the Cup is coming home: home being, of course, England. This is, of course, wishful thinking, but at this stage, it is more plausible than at any recent time. Meanwhile, outside of football, Britain struggles with the consequences of a decision to leave the EU, that has been doubled down upon repeatedly even as it began to look increasingly dubious: Parliament was whipped to irreversibly tear the brakes out of the moving car and throw them out the window. Now, as funding irregularities and connections with Russian government officials emerge, some are talking about the inevitability of a second referendum. If Britain does look like winning the World Cup, perhaps we can expect to see Westminster do a rapid volte-face, approving a second referendum and rushing it through to happen within 24 hours of the victory celebration, in the hope that a groundswell of triumphalism will translate to an increased Leave majority. And in his room deep underneath the Kremlin, the chaos-magus Aleksandr Dugin watches with a smile, knowing that everything is falling into place exactly to plan.

Brexit, Trump and one world cup, all under the watchful eyes of the Kremlin.

2018/5/26

Yesterday, the Republic of Ireland held a referendum on repealing its near-total ban on abortion. The referendum had been many years in planning: other similar referenda had failed in the past, and most infamously, one in 1983 had enshrined, in the 8th Amendment to the Irish constitution, the rights of a fertilised embryo as being equal to its mother. There was, of course, a lot of discontentment with such an illiberal state of affairs, but the death in 2012 of Savita Halappanava, a 31-year-old woman who died in agony after being denied an abortion even when her pregnancy was no longer viable, was probably what gave this push its momentum. A referendum was announced, and the campaigns started in earnest. Ireland does not allow absentee voting (otherwise its huge diaspora might sway domestic affairs from abroad), so Irish citizens from as far as Australia and Argentina made their ways back to vote. Religious-Right groups in the US sent shiny-faced volunteers with 100-watt smiles to push the No vote. Google and Facebook clamped down on Cambridge Analytica-style targeted ads, with varying reports of effectiveness.

In the run-up to the vote, all the signs pointed to a victory for the Yes campaign, to end the abortion ban. Though, as the vote loomed, the polls tightened, with some suggesting a narrow victory for Yes, with a large number of undecided voters holding sway. There was talk of large numbers of “shy Nos”, people who believed the abortion of fertilised embryos to be murder but not wishing to state this out loud and be seen as reactionary barbarians. Some said that a surprise No triumph would be Ireland's equivalent of Brexit or Trump, a chance for a silent majority of conservative left-behinds to flip the table and savour the tears of the metropolitan-liberal-elites who, until then, had believed themselves to be presiding over inevitable progress. And, of course, the possibility of the vote being swayed by the reactionary international's dark arts: ghost funding making a mockery of electoral laws, psychographically targeted ads, supposedly autonomous campaigns coördinated with military precision. Would change come, or would it be deferred for another generation? And even if Yes scraped through a narrow victory, that would give conservative legislators the cover to nobble the resulting legislation to the point of ineffectuality.

It turned out one need not have worried: the Yes case has been carried by roughly a ⅔ majority. The first exit poll gave Yes 68% of the vote; the count, with 29 of 40 constituencies declared is within a narrow margin of this. No has conceded the referendum (though of course not the divinely-mandated principle behind their position), and it looks like the 8th amendment will be repealed and laws governing the provision of abortion services, along similar criteria to elsewhere in Europe, will be passed.

(Someone I know once jested, “I'm Irish. I can do anything—except have an abortion.” It looks like she will now have to retire that line.)

This is a major shift, or rather, a sign of a major shift that had been happening for some time now. Ireland having emphatically legalised same-sex marriage a few years ago was another sign of this. The Irish republic that arose after independence, when Catholic nationalists consolidated their power—a dour, authoritarian, priest-ridden backwater, a country that condemned its unmarried mothers to penal institutions, and in which the all-powerful church vetoed the formation of a British-style national health service because secular institutions alleviating the people's misery sounded like Communism—has not existed for some time, replaced by a modern, secular nation, and only now is the extent of the transformation becoming undeniably apparent. And if there were any shy voters, it was not the mythical Silent Majority of reactionary conservatives hankering for the certainties of the good old days, but those remembering all the suffering and misery imposed by laws that have stripped women of autonomy over their bodies, many only realising after the vote that they were in the majority, not just in the entirety of Ireland but even in their own, supposedly conservative, rural province. (And the disappearance of the expected strong rural No vote, counterbalancing liberal Dublin and Cork and pushing the result to a cliffhanger, is one of the stories of the day; while final results are not in yet, exit polls have No with a majority—and a slender one—in only one of the 40 constituencies.) One big take-away may be that the myth we have been conditioned to accept, of the silent majority of public opinion inevitably being viciously reactionary, is, not to put too fine a point on it, bullshit.

The immediate consequences—Ireland's infamously restrictive abortion laws being brought into line with the liberal secular world—are fairly straightforward. What remains to be seen are the secondary effects. The most obvious one will be pressure on Northern Ireland's own draconian abortion laws. Northern Ireland, whilst a province of the UK, is run as a hard-line Protestant sectarian state, established out of fear of the hard-line Catholic sectarian state across the border. Now that that state visibly no longer exists, it will be harder to maintain it as a special case increasingly divergent from both the Republic and the rest of the UK. The evaporating power of Catholic sectarianism in the Republic may also make the formerly unthinkable—reunification—less so (especially when the alternative, reconciling Hard Brexit with the Good Friday Agreement, appears to be logically impossible). Whether the result carries beyond Ireland is another question: they're talking about legalising abortion in New South Wales now. And while a No victory would have emboldened anti-abortion activists in other countries, it's not clear whether Ireland having voted Yes will have much impact in, say, Poland or Hungary, where proudly illiberal Catholic hypernationalism is on the march.

Beyond reproductive rights, the result may be another milestone on a trading of places, culturally and economically, between Ireland and England. As Britain (though, in reality, largely England-minus-London), led by its xenophobic tabloids, voted to cut itself off from Europe, to expel foreigners and become less liberal, both individuals and businesses have been scoping out locations abroad. (You can't find office space for love or money in Frankfurt these days, and Berlin's gentrification has been accelerated by a flood of Brefugees with MacBooks.) Ireland has been cited by many as a more open alternative to the UK, though there has been a perception that it is both smaller and more parochial. The Irish electorate's recent decisions are likely to put paid to the second objection: the first may last a little longer, but if one remembers what low esteem, say, dining in Britain was held in a few decades ago, or the sleepy, bureaucracy-ridden nature of doing business there, it may not take long for Dublin to displace London altogether.

2017/3/9

I have just spent a little over two weeks in Melbourne; I arrived on occasion of a conference on iOS development, but stayed longer to give me time to catch up with friends. It was my first visit to my old hometown in almost five years.

Melbourne is, I am relieved to say, still here. Just about. Some things are new, some things are gone, and some things remain constant.

Gentrification keeps pushing the virtual Yarra that divides bourgeois and grungy Melbourne northward; it'd now be somewhere around Merri Creek and Brunswick Road.

Fitzroy feels a bit more like South Yarra, a bit brasher and less bohemian. Hip-hop, laptop R&B and house music have largely displaced skronky/jangly indie-rock as its soundtrack. Brunswick Street is now is also a destination for stag/hen-party buses.

Some parts of it are gone (PolyEster Books has closed down, its shopfront a sad shell with a LEASED sign on it and the old roof sign awaiting its inevitable demolition, and the T-shirt shop Tomorrow Never Knows appears to have closed as well), while others remain (PolyEster Records, happily, is still going strong, though they've gotten rid of the neon Dobbshead that was on the wall, as is Dixon Recycled, and Bar Open is still hosting interesting gigs). Smith Street, once colloquially known as “Smack Street”, is reshaping itself as a playground for young people with disposable income, featuring, among other things, several video-game bars (including the arcade-machine bar Pixel Alley) and a burger joint housed inside the shell of an old Hitachi train on the roof of a building (the experience of being inside such a train and it being air-conditioned will be incongruous to those old enough to remember riding in them), not to mention some very nice-looking new flats nearby. There is a new generation of hipster/bro hybrids making Fitzroy their stomping ground. North Fitzroy is largely bourgeois and sterile; bands still play at the Pinnacle, but the Empress, once the crucible of the Fair Go 4 Live Music movement, is under new management and has replaced its bandroom with a beer garden; East Brunswick and Thornbury seem to be becoming more interesting, and Northcote is steadily gentrifying. There are blocks of luxury flats going up everywhere, though most of them have no more than three stories, either because of zoning requirements or perhaps to avoid scaring away buyers from Asia.

Some parts of it are gone (PolyEster Books has closed down, its shopfront a sad shell with a LEASED sign on it and the old roof sign awaiting its inevitable demolition, and the T-shirt shop Tomorrow Never Knows appears to have closed as well), while others remain (PolyEster Records, happily, is still going strong, though they've gotten rid of the neon Dobbshead that was on the wall, as is Dixon Recycled, and Bar Open is still hosting interesting gigs). Smith Street, once colloquially known as “Smack Street”, is reshaping itself as a playground for young people with disposable income, featuring, among other things, several video-game bars (including the arcade-machine bar Pixel Alley) and a burger joint housed inside the shell of an old Hitachi train on the roof of a building (the experience of being inside such a train and it being air-conditioned will be incongruous to those old enough to remember riding in them), not to mention some very nice-looking new flats nearby. There is a new generation of hipster/bro hybrids making Fitzroy their stomping ground. North Fitzroy is largely bourgeois and sterile; bands still play at the Pinnacle, but the Empress, once the crucible of the Fair Go 4 Live Music movement, is under new management and has replaced its bandroom with a beer garden; East Brunswick and Thornbury seem to be becoming more interesting, and Northcote is steadily gentrifying. There are blocks of luxury flats going up everywhere, though most of them have no more than three stories, either because of zoning requirements or perhaps to avoid scaring away buyers from Asia.

Melbourne feels increasingly connected to Asia. In particular, the CBD has become a destination for a combination of property buyers and students from Asia, from bubble-tea bars and a surfeit of Chinese and south-east Asian eateries aiming outside the westernised market to real-estate dealerships aiming at the Chinese market. While there are fewer Japanese migrants and students, the cultural and commercial influence of Japan has been increasing. Japanese food is everywhere; there are increasingly many establishments festooned with red lanterns and purporting to be izakayas, some of which are more authentic than others (Wabi Sabi on Smith St. was excellent), ramen restaurants are popping up, as are Japanese ice cream shops; and then, of course, is the several-decades-old Melburnian institution of takeaway sushi rolls, served in a paper bag with a piscule of soy sauce, as unpretentious fast food. Japanese retail is also making inroads; Uniqlo and Muji have opened shops in Melbourne and the T-shirt label Graniph have a small shop in the CBD. But perhaps most impressive is the Japanese take on the $2 shop, Daiso, a veritable Aladdin's cave of the useful and nifty, each item costing a flat $2.80. (European readers: imagine the Danish chain Tiger/TGR, only distinctly Japanese, with the scale and systemacity that implies.)

Some things remain the same. The trams keep trundling along, with minor route adjustments. The radio station 3RRR, now 40 years old, is going strong as an institution of the alternative Melbourne; an exhibition on its history just finished at the State Library of Victoria, and its stickers are ubiquitous, particularly in the inner north. The live music scene continues apace, in venues such as the Old Bar, Bar Open and the Northcote Social Club. (I saw three gigs in the latter: Lowtide, Pikelet and my favourite band from when I lived in Melbourne, Ninetynine, who are still going strong.) Street art remains an institution in Melbourne, a city where aerosol-art-festooned laneways swarm with tourists and wedding photo shoots and businesses hire “writers“ to decorate their walls with thematic pieces. And the arrival of H&M, in one oddly laid out shop occupying the former General Post Office, doesn't seem to have put Dangerfield out of business.

There are also signs of progress.

Reconciliation with Australia's indigenous population seems to be making tentative symbolic advances, with signs acknowledging the Wurundjeri as traditional owners, and the Wurundjeri word for welcome (“wominjeka”) appearing on signage. Solar panels are on roofs everywhere.

Reconciliation with Australia's indigenous population seems to be making tentative symbolic advances, with signs acknowledging the Wurundjeri as traditional owners, and the Wurundjeri word for welcome (“wominjeka”) appearing on signage. Solar panels are on roofs everywhere.

Cycling as transport seems to be increasingly popular, despite Victoria's mandatory helmet laws (which may have helped scuttle the city's Paris-style bike-rental scheme). And work is beginning on the state's first big public-transport project since the City Loop, the Metro Tunnel, a new underground rail route bringing Melbourne into the club of cities with a subway; currently, one side street near RMIT is largely boarded off to build a shaft for the tunnel boring machines, and both RMIT and Melbourne University are bracing for the hit to student numbers that three years of nearby disruptive works will pose.

Cycling as transport seems to be increasingly popular, despite Victoria's mandatory helmet laws (which may have helped scuttle the city's Paris-style bike-rental scheme). And work is beginning on the state's first big public-transport project since the City Loop, the Metro Tunnel, a new underground rail route bringing Melbourne into the club of cities with a subway; currently, one side street near RMIT is largely boarded off to build a shaft for the tunnel boring machines, and both RMIT and Melbourne University are bracing for the hit to student numbers that three years of nearby disruptive works will pose.

2016/10/12

In recent social psychology news, a team of US researchers has debunked the myth of the Baby Boomers' strong work ethic:

The economic success of the United States and Europe around the turn of the 20th to the 21st century is often ascribed to the so-called Protestant work ethic of members of the baby boomer generation born between 1946 and 1964. They are said to place work central in their lives, to avoid wasting time and to be ethical in their dealings with others. Their work ethic is also associated with greater job satisfaction and performance, conscientiousness, greater commitment to the organization they belong to and little time for social loafing.Hang on, I hear you say: the stereotypical Baby Boomer work ethic? The generation born between 1946 and 1964, that of Beatlemania and Woodstock, long hair, Free Love, anti-Vietnam-War protests and recreational drug use (and, at its younger end, shading into the fuck-the-system nihilism of punk), being associated specifically with duty, discipline and delayed gratification? That can't be so. Perhaps whoever came up with that idea skipped a decade or two, and was instead thinking of a slightly earlier cohort; perhaps their older half-siblings, the neatly groomed beige-suited Eddie Haskells who addressed their parents as “sir” and “ma'am”, or even the “Greatest Generation” who sacrificed everything in World War 2, only to watch their kids grow their hair, listen to that godawful racket, and generally not exemplify a particularly strong work ethic.

The other possibility is, of course, that the stereotype of the “Baby Boomer work ethic” is not so much about the Woodstock generation but about old people. Which is to say, that it reflects survivor bias; the likelihood that the ones left standing into advanced age either had their shit together from the outset or got it together. Presumably, of the generation that came of age in the heady Sixeventies, some will have fallen by the wayside (and, of course, Reaganism, AIDS and punk rock were just around the corner), some will have grown up and gotten with the programme (this was in the day before emoji and executive hoodies, when adulthood was a one-way transformation into a stolid mortgage-paying lump of joyless responsibility), and some, seeing that they had survived and succeeded, would have rationalised that they had been hard-working and responsible (and, thus, deserving of their success) all along. Which, of course, vacated the space of feckless irresponsibility for the younger generation, to whom it always belongs.

Of course, what this means is that, in some 20 years' time, we can look forward to a paper debunking the widely held stereotype that Generation X—the one most recently associated with MTV, “alternative rock”, Nintendo and the “slacker” stereotype—are inherently more moral, virtuous and upstanding than their shabby, feckless descendants. And then, eventually, it will be the millennials, the generation of selfies, Taylor Swift and crushing debt. And, in turn, every generation will, shortly before its death, briefly be the Greatest Generation standing.

2016/9/5

Observing political debate, I have noticed a trope that keeps recurring, particularly (these days) on the Right. I'll call it the Gordian Knot Delusion. It says, in essence, “the so-called experts/eggheads/‘intellectuals’ keep going on about how complex things are, but they're liars. When you get down to it, things really are simple.” (There is an implicit “Watch this!” after that, as the speaker purports to bulldoze their way through some issue that namby-pamby liberals and ivory-tower boffins have been wringing their hands ineffectually over, like the two-fisted, lantern-jawed hero of one of those old sci-fi paperbacks the Sad Puppies lament aren't being written any more.) An example of the Gordian Knot Delusion, on that favourite subject of taxes/economics, recently manifested itself in the following tweet from Conservative commentator Daniel Hannan:

It does not need to be pointed out that this is an extremely simplistic argument, more an act of trolling (in its original sense of seeking to provoke a pile-on of responses) than a serious inquiry in good faith, at least, if one assumes that the author is not a simpleton. It achieved its aim, in that others piled on with rebuttals on the same level, along the lines of “if olive oil is made of olives, what is baby oil made of?”. But if one takes the premise beneath it at face value, or at least treats it as something more meaningful than wordplay, the Gordian Knot Delusion comes through. Taxes disincentivise prosperity, it implies, unqualifyingly; cut taxes to the bone and watch prosperity take off like a rocket. And ignore the tweedy, elbow-patched fellow there saying that it's more complicated than that; the man looks like a commie, and is probably after your piece of the pie.If tobacco taxes disincentivise smoking, and petrol taxes disincentivise driving, what do you suppose income taxes do?

— Daniel Hannan (@DanielJHannan) September 4, 2016

The Gordian Knot Delusion, the idea that things are simpler than they are claimed to be, is trotted out by amateur spectators in a lot of fields. Economics is a big one: witness the “common-sense” idea that national economies work like household budgets, with a largely fixed income that is unaffected by the level of spending. By this token, one can believe that deficit spending is inherently irresponsible and austerity is, in itself, good economic housekeeping. (This, of course, falls apart when one considers that economic activity generates wealth, and that savings at rest have no economic impact, but it feels enough like common sense that one can persuade oneself that these objections are sophistry by ivory-tower eggheads, Marxists and moochers.) Ecology and the environment are another area; nobody can see global warming, or when they can, one can believe that the evidence is still out, (or once it isn't, it's too late to do anything so crank your air conditioning up and enjoy the ride); and as for that habitat of endangered newts the hippies are protesting about, let's just drive a motorway through it and see what happens; betcha that everything will be alright. The bees are dying off? Who cares about a buncha dumb bugs! The coral reefs are too? The tabloids say they're not. And if they are, so what?

And then there's modern society in general: gender-neutral job titles and ladies wearing trousers and lactose-free milk in the supermarket, oh my! Your son, who used to be your daughter, is taking medication for ADHD, your other daughter has a girlfriend, your boss wears a nose ring, and the golliwog doll from your childhood is now a potential hate crime. In the good old days, these things didn't exist, or if they did, they were hammered flat like a lump under the rug; people accepted their lot in life, and, as the refrain goes, everything was alright. (One part of this is the myth that these complex conditions, from gluten intolerance to gender dysphoria, don't actually exist, but are made up by an unholy alliance of bureaucrats, drug companies, the liberal media and people who want to feel like special snowflakes; the corollary: were it not for the conspiracy, a sharp clip around the ear would sort them out just as well.)

At its core, the Gordian Knot Delusion is an application of the 80/20 rule to the modern world at large; the belief that complexity is superfluous, and that rather than fretting over it, one should just stride over and cut the knot, deciding that the world is actually simple; witnessing the lack of an immediate catastrophe, one will find one's common sense and derring-do vindicated. (The original Gordian Knot was cut by that gung-ho man of action, Alexander the Great, which is always a flattering comparison.) The other part of the Gordian Knot Delusion is the stab-in-the-back narrative of how the world started to look deceptively complex. As the paranoiac's dictum goes, shit doesn't just happen, but is caused by assholes; in this case, all that talk about how complex things are is the work of a conspiracy; a motley crew of commie traitors, ivory-tower academics, so-called “intellectuals” corrupted by book-learning, miscellaneous perverts, Satanic cultists and out-and-out crooks and thieves out to keep the gravy-train of complexity going, all the better to steal from the simple honest folks. (The trope about climate change being a massive fraud for the purpose of maintaining funding for otherwise worthless research is a classic of the genre.) It is, as conspiracy theories tend to be, a compelling story, especially those who feel themselves bewildered or victimised by the world.

Whilst ostensibly associated with the Right these days, the Gordian Knot Delusion is actually the very antithesis of Edmund Burke's Conservatism, formulated in the wake of that catastrophic leftist severing of this knot, the French Revolution. Burke's argument (framing Conservatism for a world where the divine right of kings was no longer accepted and the University of Chicago School of Economics had yet to come into being and coin its modern analogue, trickle-down economics) was that things are much more complicated than one can comprehend, that bold attempts to destroy ancient injustices are also likely to have countless unintended consequences, and that one should stick to gradual, tentative reforms at best, if not to just give up and learn to live with the world as it is in all its richness and iniquity. Today, one might expect to hear that sort of argument, but only from a hair-shirted greenie warning against tampering with Mother Gaia's blessings. The Robespierres of the Right are all too happy to break things and observe that, on a macro level, everything is alright (whilst circularly classifying those for whom they are not alright as bums and sore losers). These radicals are in alliance with a growing number of people who are anything but radical in temperament, but who have been radicalised by the rapid pace of change, and for whom the idea of turning back the clock to (what in retrospect seems like) a simpler time has appeal. The shift of the Gordian Knot from the Left to the Right could be a result of the increasingly rapid pace of social and technological change.

2016/8/18

This week I was at The Conference in Malmö; here are a few of the things I learned:

- People are moving away from social media (like Facebook/Twitter) in favour of 1-to-1 messaging apps (and group apps) like WhatsApp and Slack. This is partly due to messaging being more immediate, and partly due to social concerns such as privacy and the need to be able to engage differently with different people one knows (i.e., your coworkers don't need to see your family photos). In some places, there are businesses which run entirely on messaging platforms: gyms whose only point of contact is a phone number linked to WhatsApp, and property transactions in which the legal documents include screenshots of banking app transfer screens.

- Minecraft is teaching kids a lot of useful skills, from digital logic (building machines using redstone gates) and computational/design thinking, to social skills from self-organising build teams to designing and enforcing social contracts to protect from griefers. A big part of its success is because it is not a top-down product handed down from the authorities, like, say, Scratch or Swift Playgrounds, but something the kids can do whilst out of sight of grown-ups (much like the Commodore 64 back in the day).

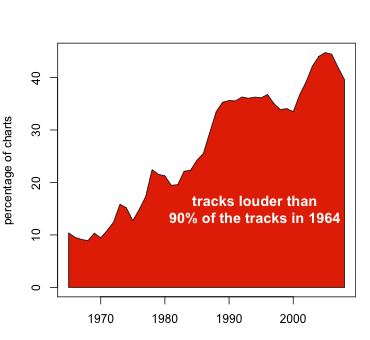

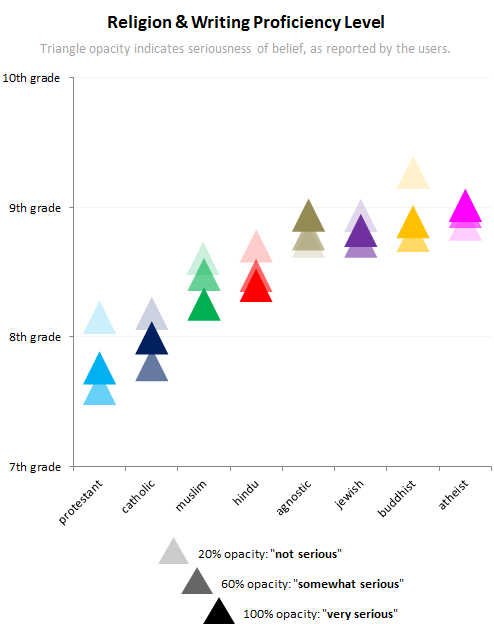

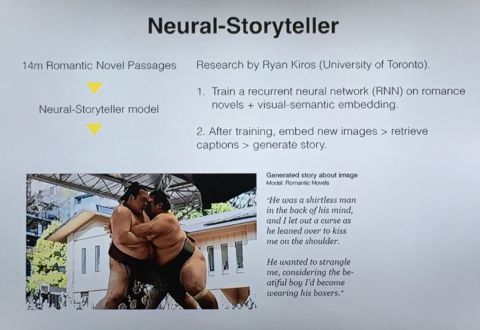

- There is a lot happening with generative art. The most familiar form, describing a space of potential outputs parametrically and searching the parameter space by one means or another, is common enough, and appears in settings from art installations to

web appsTwitter bots. Now, advances in neural networks and deep learning are making an impact. Style transfer (think apps like Prisma, the photo-styling app for mobile phones, but also software for cleaning up rough sketches or colourising black-and-white images) has the potential to democratise or commodify (depending on whom you ask) artistic style. Meanwhile, deep learning with multiple media can produce synaesthetic examples, like the following output of a network trained on the text of romance novels and subsequently fed an image of a sumo match: - Smart cities, digitised to the millimetre with LIDAR, surveilled by drone, and managed by app, promise an end to the long nightmare of politics. Now a city can be run from above by impartial, objective algorithms—Plato's Philosopher King rendered in code. Everything in its right place, every space accounted for, all inhabitants managed with the efficiency of an Amazon warehouse, and all the dogs in the city are walked by drone. Until feral ravers disrupt the city's fiducial architecture (the patterned markers which guide the drones), conceal themselves from its managerial gaze with dazzle make-up and asymmetric haircuts, hijack the self-driving taxis and party in the spaces the machine does not see.

- Then again, one objective true point of view is a myth. The Jesuits found this out when, in an attempt to Christianise China, they tried to persuade the Chinese of the superiority of European-style one-point perspective over the aerial perspective used in Chinese art (which they saw as backward and inferior, for its ignorance of the point of view).

- The term “Perspective Collision” describes what happens when designed objects inadvertently reveal their designers' limited perspectives. Examples include camera film not showing dark-skinned people properly, or air conditioning in buildings being optimised for men. This is related to the Malkovich Bias, the idea that everybody uses technology the same way one does.

- Animal-free animal products are starting to appear. There now exist genetically engineered yeasts which, when fed with sugar, produce egg albumen and bovine casein, i.e., egg white and cow's milk. These are identical to the real products on a molecular level, and can be used for all the things real egg white/milk can be used for (as opposed to current animal-product substitutes, which tend to be specific to various uses). Actual animal-free meat is taking a little longer (growing more than thin layers of meat requires some form of structural scaffolding to feed the cells). This is known as cellular agriculture, and, once it matures, will work a lot like brewing: artisans/craftspeople managing a technical process.

- Stereotypical images used to represent the idea of “young people”: cartoon figures with shaggy/spiky hair and horizontally striped shirts; strobing photographs of wild-looking rock concerts.

- National Geographic, famous in popular culture for publishing photos of bare-breasted “exotic” non-Western women (something it has been doing since the 19th century), published its first photo of a bare-breasted white woman in 2016

2016/1/11

The buzz of my phone cut through the remnants of a fading dream this morning, a notification of something happening in the waking world. I picked up the handset and saw on its screen two items, from two different media outlets on opposite sides of the Atlantic, announcing the seemingly preposterous: two days after having released his new album (on his 69th birthday), David Bowie had suddenly died of cancer. Surely this cannot be the waking world?

It turned out to be real enough. In the minutes that followed, the trickle of incredulous queries turned into a torrential flood of mourning, commemoration and sombre celebration of an epic life. MetaFilter got its usual river of mournful .s. Facebook and Twitter were wall-to-wall Bowie all day. The Guardian ran a liveblog and a surfeit of articles and thinkpieces, with seemingly everybody other than George Monbiot giving their take on Bowie's significance. My Spotify sidebar was almost entirely Bowie (the sole outlier being someone in the habit of listening to their algorithmic playlists).

I had been meaning to listen to the new Bowie album, ★ (or Blackstar), today on Spotify, before probably buying a copy. It was officially a mere two days old, though had been completed months earlier. Much like his previous album, 2013's The Next Day, it had been made in secret, its release synchronised to Bowie's birthday. Though while The Next Day was perhaps necessarily backward-looking, from the Heroes-sampling artwork to its 1970s rock stylings, to the nostalgic melancholia of Where Are We Now?, Blackstar couldn't be more different. Recorded with entirely new musicians, from a jazz background, a shifting assemblage of sounds; a Middle Eastern scale here, some drum'n'bass-style beats there, the mood shifting between skilfully crafted pop and the ominous and unsettling; oblique references to executions, hospitals, being in heaven with invisible scars and never seeing the trees of England again, and a final track titled I Can't Give Everything Away. In the handful of days and weeks various people had to hear it before the truth came out, there was much speculation; was it a response to atrocities in the Middle East? Did it signify the dawn of a new late period of intense creativity on Bowie's part? If anybody had put the pieces together, they kept their mouth shut.

After the news got out, Bowie's long-time producer Tony Visconti, who had spent the past year working secretly on the album, revealed that it had been intended all along as a parting gift; Bowie, diagnosed with cancer and knowing that his time was limited, had recruited him and a few musicians and worked on it for a year. He had played fair, creating something that would be seen for what it is only in retrospect. David Bowie's final artistic work was the presentation of his death and transition to history. Even the title is a clue: in astrophysics, a black star may be a transitional phase between a collapsing star and a singularity; and the artwork, being the only album to lack Bowie's image on its cover; perhaps alluding to his imminent absence from the world. (I wonder whether the designer, Jonathan Barnbrook, knew the full story behind his brief.)

I was a little too young for David Bowie's music have been directly part of my formative experiences (my adolescence coinciding with the forgettable Tin Machine, rather than his liberatingly transgressive Ziggy Stardust/Aladdin Sane era, the monochromatic artistic explorations of his Berlin period, or even his early-1980s pop breakthrough), but Bowie was in the background, directly and indirectly. His big hit Let's Dance, angular and night-coloured, is a fixed memory, overheard in fragments hundreds of times in my childhood—in my fragmentary child's-eye perceptions, its staccato horns and woodblocks merge with punk plumage and rudeboy checks into a tapestry of edgy, transgressive early-1980s youth counterculture, vaguely forbidden with admonitions about drugs and criminality—and immediately taking me back (a honour it shares with Roxy Music's More Than This); other songs, from Rebel Rebel to Ashes To Ashes, also were familiar before I ever knew whom they were by. I would pick up the thread many years later, with the 1969-1974 singles compilation. I went to parties where his 1970s albums played in the background, put on by people who were older than me or who had inherited older siblings' record collections. (The influence of David Bowie was a constant in Melbourne from the late 1970s onward; see also: Dogs In Space.) The music I would end up listening to myself (and the first record I ever bought was a New Order 7") was influenced by him, (even though it generally emerged on the other side of that notional Year Zero known as punk; in reality, there is no such thing as Year Zero). With Bowie gone, the memories his music brings up suddenly feel a lot more distant, as if a thread holding them closer had snapped.

My feelings at the moment are a roughly equal mixture of shock (and reflection on the passing of time and the inevitable end of everything) and admiration for a person who died as he lived, using his own imminent death as art material. This week, I will stop by at Rough Trade and pick up a copy of Blackstar. For one, they are donating the proceeds from their sales of David Bowie records to Cancer Research this month.

2015/10/20

The BBC has a new documentary series about the history of indie music, specifically in the UK; titled Music For Misfits, it follows the phenomenon, from the explosion of do-it-yourself creativity unleashed in the wake of punk, running throughout the 1980s like a subterranean river, largely out of sight of the high-gloss mainstream of Stock/Aitken/Waterman, Simply Red and Thatcherite wine-bar sophistipop, channelled through a shadow infrastructure of photocopied zines, mail-order labels selling small-run 7"s and reviews in NME and Melody Maker (which, it must be remembered, had countercultural credibility back then, and were run by people whose business cards didn't read "youth marketing professional"), surfacing in the 1990s into the new mainstream of Britpop (much in the way that its American counterpart, alternative music, had become a few years earlier with the grunge phenomenon), before finally coalescing into a low-energy state in the new millennium as the marketing phenomenon known as Indie, a hyper-stylised, conservatively retro-referential guitar rock sponsored by lager brands. Though by the third episode of this series (the 1990s one), the BBC seems to succumb to this very revisionism of the term "indie", and, as Emma Jackson of Kenickie points out, retroactively edits almost all women out of the story, presumably because otherwise it wouldn't jibe as neatly with what modern audiences understand "indie" to mean:

It wasn’t just the lack of voices but the choice of stories that were included. No mention was made of the Riot Grrrl movement. Including the story of Riot Grrrl would have easily linked up with the previous programme’s section on fanzines and C86. Riot Grrrl also complicates the idea that British indie was in a stand off with US music. Rather in this scene bodies, music and fanzines travelled across the Atlantic and influenced each other. Also, while in indie music ‘white is the norm’ as Sarah Sahim recently argued, the Riot Grrrl moment in the UK also included bands lead by people of colour such as The Voodoo Queens and Cornershop (who had a number one on the independent Wiija in 1997).

Some major players were also missing. You have to go some lengths to tell the story of Britpop and not mention Elastica, but that’s what happened in the programme. There was a very short clip of them that flashed by. Or Sleeper. They were huge. Or PJ Harvey. Or Lush. Or Echobelly. Or Shampoo.Perhaps this is all a clever meta-narrative device, highlighting the issue of the blokeification of the term "indie" that is concomitant with it having ceased to be a structural descriptor ("indie" as in independent, from the major labels, from commercially manufactured pop music, the materialistic cultural currents/right-wing politics of Reaganism/Thatcherism, or what have you), and having become a stylistic descriptor (you know, guitars/skinny jeans/Doc Martens/Fred Perry/Converse/reverent references to an agreed-upon canon of "cool" bands from the previous half-century), and soon after that, a signifier of Cool British Masculinity, in the way that, say, Michael Caine, James Bond movies and various East End gangsters of old used to be. Perhaps it's a monumental oversight, inexplicable in hindsight, an oh-shit moment as the programme goes out. Or perhaps the original outline for the programme had sections on Bratmobile and Lush and Dubstar, which ended up on the cutting room floor after some risk-averse executive ruled that putting them in would weaken the narrative, confuse the audience or induce the Daily Mail to scream about "political correctness".

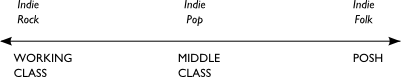

The equation of indie with retro probably didn't help. The seeds were sown in the underground 1980s, along with the rejection of the glossy commercial pop of the decade (which was partly a practical matter, with the kinds of high-tech studios the Pete Watermans of this world used to craft their chart-toppers costing millions, while electric guitars and Boss pedals were cheap), though became codified in the Britpop era, when journalist after lazy journalist equated the bold new age of British Guitar Rock with that last imperial phase of UK pop culture, the Swinging Sixties. Soon this became a self-fulfilling prophecy; things which didn't fit the narrative were pushed to the side, vintage Lambretta scooters and Mod roundels started showing up everywhere, and the Gallagher brothers, gazing down red-eyed from the heights of Snow Mountain, announced themselves to be the second coming of John Lennon, returned to bring proper rock'n'roll back to the people. Somewhere along the way, this retro rockism absorbed some of the retro sexism of the post-ironic lad mags of the time, marinated in the reactionary miasma inherent in the idea of a lost "golden age" (one before all this modern nonsense, when music came on vinyl and dollybirds knew their place was hanging on a geezer's arm, and so on), and so was born the New Lad Rock, whose name, in time, was lazily shortened just to "indie"; in its moribund terminal state, the Yorkie bar of music, right down to the "Not For Girls" label on it.

(Of course, the problem with looking backwards is often also the fact that those inclined to look backwards tend to fixate on forms rather than the processes that they emerged from (as the forms are the obvious thing to grasp, especially if one is not analytically inclined) and draw reactionary conclusions. For example, the fetishisation of the two-stroke motorscooter, a symbol of teenage freedom in the 1960s (it's probably no exaggeration to say that the Vespa was the MySpace Facebook Snapchat of its age), but a dirty, cranky, inefficient antique these days. Or, indeed, the actual careers of the cultural heroes. So, while the Beatles experimented with musique concrète and Mick Jagger subverted (to an extent) the meaning of masculinity, none of this is evident in the plodding, workmanlike homages to "proper rock" of their self-announced modern-day followers.)

The equation of stylised "indie" rock with a retrograde "lad"/"geezer" masculinity seems to be firmly embedded in the culture of this day; only recently the radio station Xfm, which originated back in the day with an indie-music format, was rebranded, explicitly, as a blokey-guitar-rock station, without too much loss of cultural continuity. The next logical step would be would be to introduce a musical segment into the upcoming reboot of men-and-motors TV show Top Gear (which, of course, is already to be fronted by a Britpop-era radio DJ), where, between the high-octane stunts, a band of lads with guitars and Mod haircuts take to the screen and play something that sounds like a stodgily conservative take on the Beatles/Kinks/Clash/Pistols/Stone Roses.

(via Sarah_Records) ¶ 0

2015/4/6

It is an early afternoon during the Easter bank holiday weekend, at an indiepop weekender at an art venue in Cardiff. A band is playing on stage, fuzzy guitar lines, drums and female vocals mixing together. The audience, or those who have arrived early, are standing and watching; they tend to be in their mid-30s and older; women wear hair slides and floral/polka-dot dresses, while the Mod Dad look, with Fred Perry polo shirts, short hair and sideburns, is popular among the menfolk. In front of the stage, what might have once been the mosh pit is now a children's play area, replete with LED-illuminated balloons. about four or five young children run around, squealing and bouncing the balloons. Wearing ear protectors, they appear to be unaware of the grown-ups on the stage holding guitars, the relationship between them doing this and the sound coming out of the speakers, or that there would be any reason to not run around in front of the stage. The concept of a “gig” seems to be alien to them. Elsewhere, smaller children bop gently up and down in time to the music in their mothers' hands, animated by parental enthusiasm; they gawp bewilderedly, their faces showing only undifferentiated emotion. The squawls of babies fill the gaps between songs and add a novel accompaniment to the jangly melodies. Occasionally, a musty odour fills the air and a balding guy in a faded Milky Wimpshake T-shirt leaves hurriedly, carrying a discomforted-looking infant to a baby-changing area.

Once upon a time, pop/rock/alternative music consumption was strictly for teenagers; you got into it when the adolescence hormones hit your bloodstream and you needed something that was yours and not your parents', spent a few years spending your pocket money on 7" records and dressing in a way your grown-up self might later find as embarrassing as your parents did at the time, and dropped it just as quickly when you Grew Up, got a job, married and had kids of your own and were saddled with the burden of adult responsibilities which you would carry unto the grave. Gradually the boundaries got pushed back, and a whole market of “adult-oriented rock” emerged; engineered to soothe the nerves of stressed Responsible Adults whilst providing them with just enough of a hit of what excited their younger selves a quarter-century earlier, it tended to a sort of soaring, platitudinal blandness; a weak substitute for what had been forfeited. Though over the past few decades, the idea that one must check one's musical/subcultural identity at the door of adulthood has been eroded even further. The pioneers may well have been the Goths, who stubbornly refused to Grow Out Of It well into middle age and beyond; though soon, the commodification of cool into cultural capital opened the doors further, until soon we had shops in trendy areas selling Ramones baby clothes and lullaby renditions of The Cure and Nirvana, and bands classified, back-handedly, as “dad-rock” or “dad-house”. This isn't completely universal—after all, supermarkets flog millions of records by the likes of Coldplay and Ed Sheeran for people who either never were into music or else vaguely remember what it felt like but have no desire to regress to that phase of their lives—but one no longer has to be a fringe-dwelling bohemian to remain particular about music

Of all the genres and subcultures, though, the indiepop scene seems to have become uniquely small-child-inclusive. As a critical mass of indiepop kids hit middle age and have kids of their own, they are more likely to bring them, en masse, to gigs and festivals, and adapt the events themselves for the kids; songs with rude words are dropped or bowdlerised, balloons are provided, and the gig becomes a mass playdate first, and a musical performance only tangentially to this. Flocks of toddlers run around, yelping and shouting gleefully, and it is seen to be their right to do so; anybody who objects to this getting in the way of their enjoyment of the music may as well be a fascist or a Tory or something equally unspeakable. The music's almost just a side product for the parents' benefit. Elsewhere, there are indiepop baby discos, acclimatising young ears to Belle & Sebastian and Allo Darlin' from an early age. Perhaps, elsewhere, there are pint-sized punks pogoing anarchically to toddler-friendly renditions of Anarchy In The UK, baby discos spinning gnarly brostep, or black-clad toddlers running around like swarms of ground-hugging bats at the Whitby Gothic Weekend, but such possibilities notwithstanding, this seems to be peculiar to indiepop. There are no boisterous toddlers at, say, shoegaze, psych or post-rock gigs; other festivals may have a few small children in attendance, but they are fewer in number, and where special provision has been made for them, it is away from the stages.

Why indiepop has, upon its members' parenthood, shifted wholesale into a toddler-friendly environment is not certain. Perhaps it's a natural outgrowth of the “twee” signifier, which originated in the 1980s as a rejection of the hypermasculinity of hardcore and/or post-punk rock, instead embracing, with varying degrees of irony, the signifiers of childhood. Much in the way that things that start as ironic appropriations often end up shedding the irony and continuing with some degree of sincerity (as seen, for example, with the “ironic” sexism of 1990s “lad” magazines), a scene whose zines and button badges copied old children's books might transform from a subculture questioning the inherent conservatism in the childish/mature dichotomy to a subculture tailor-made for small children and their parents.

It'll be interesting to see whether the toddlerification of indiepop changes the subject matter of it more than removing the word “fuck” from lyrics. Thematically, indiepop songs do tend to hover around adolescence and its long decay envelope, with themes of crushes, break-ups and being in or out of love cropping up disproportionately often. These days, this is even more so than in, say, the C86 days, as “twee” became stylised and codified into a somewhat excessively fey, cupcakey aesthetic, and some of the oddness of 1980s-vintage indie has been replaced by chaste adolescent romance like a plot from an Archie comic soundtracked by vintage Motown girl groups. Perhaps as the under-5 demographic at indiepop gigs swells, these themes will be displaced to some extent by songs about dinosaurs, monkeys, pirates, rocket ships, monkeys who are rocket-ship pirates, poop and other things more likely to appeal to actual small children.

Secondly, it will be interesting to see what a generation of kids who were brought up listening to twee pop from birth end up doing when adolescence, and the need to individuate themselves, hits them.

2015/2/4

Apparently Finland's school system is scrapping cursive writing lessons in favour of typing. In other news: apparently, in the 21st century, children are still taught cursive writing in schools:

"There's research shows us that a child will have a better concept and better memory for what a letter is and what it represents if they actually handwrite it ... [but] the argument is really against those pages of cursive, joined-up writing exercises which, in the end actually don't change many people's hand writing styles... Cursive writing is cute, and nice, and decorative if you've got a leaning towards wanting to do it ... just like you might like to learn to crochet or knit.

"The handwriting exercises that we do are really based on very old technology," she said."So when we teach kids particular downstrokes and where to start their letters, it's really based on how you had to use the technology of a fountain pen and ink."Cursive writing is a funny thing; it's not quite practical (who writes an essay under exam conditions cursively, and who finds that more legible than neatly separated printed script?), and it's not quite decorative (it stops well short of anything that could even generously be called “calligraphy”). Its sole raison d'etre is tradition (that teaching children fountain-pen-era techniques is in some ways useful), if not an authoritarian, vaguely punitive disciplinary mindset (idle hands are the devil's plaything, and those little hell-apes that we call children must have their rebellious spirits broken with laborious exercises lest they get up to mischief). Perhaps killing it off as a mandatory part of the curriculum could be the best thing for it: once it's no longer compulsory, and is as alien to the average person as film photography or slide rules, some subset of artisanal crafters and/or hipster contrarians will take it upon themselves to revive this vintage skill and take it further than it would have otherwise gone?

The article, on ABC News, speculates on the possibility of Australia following the Finnish lead and removing cursive writing from its schools. I expect that will happen somewhere around the time of them ditching King Charles III as their head of state and abolishing Imperial honours for the second time in history. I can imagine the ultra-conservative establishment running the country wouldn't have a bar of any such proposal, and indeed can almost read the column in The Australian denouncing the very idea as proof that the Marxists have taken over the teaching profession.

2015/1/22

I am writing this on a train to London from Birmingham, where I have spent the past two days at an academic conference about the electronic music group Kraftwerk. There were some 175 people in attendance; their ages varied from those who had not yet been born during Kraftwerk's heyday to a sizeable contingent of (mostly) men of a certain age who had been at various legendary shows back in the early 80s. The conference, whilst theoretically an academic conference, was open to the general public, and the talks presented varied from critical-theoretical analyses of the signifiers in various records to autobiographical monologues.

The conference began with Stephen Mallinder, of Cabaret Voltaire, talking autobiographically about his own experience of Kraftwerk and how they inspired his and his bandmates' own music-making; he mentioned that, back in the 1970s, he and his mates would refer to traffic cones as “kraftwerks”. Later, Nick Stevenson talked specifically about Cabaret Voltaire, the Sheffield scene, their use of Dadaist techniques and Burroughs' cut-up technique, and the themes of “the control culture” in their music. Other than that, the rest of of the first day was occupied with going through Kraftwerk's early career and first few albums, as well as the “archaeological period” of the three pre-Autobahn albums one gets the impression Ralf Hütter would rather were struck from the historical record. David Stubbs, author of the recent Krautrock book Future Days, talked about this period, tracing the band's history from their shambolic start as The Organisation (which, in surviving footage of live performances, looks like an “on-the-nose parody of Krautrock” in all its scruffy, hippie shambolicness), through the first three albums—Kraftwerk 1 (whose pastoral sound prefigured what Boards Of Canada would do several decades later), Kraftwerk 2 (where the potential of drum machines first appeared) and Ralf & Florian (which, in its title and cover photograph, showed the artists starting to make themselves part of the artwork, perhaps echoing Gilbert & George, who had visited Düsseldorf in that period). This was followed by a talk by David Pattie, a Glaswegian academic, elaborating on Ralf & Florian and from that, the question of Kraftwerk's relationship with Germanness. Among other things, Pattie pointed out a progression in the works of Kraftwerk and other West German bands (Can, Popol Vuh, Tangerine Dream, Neu! and Kluster/Cluster) through the early 70s; a divergence from pure rhythm and/or noise and rediscovery of melody in subsequent albums, and put forward the theory that all these bands had initially set out to reject the musical heritage of their forefathers, and gradually come to an accommodation with it.