The Null Device

Posts matching tags 'psychology'

2014/12/21

Youth subcultures, as many middle-aged former teenagers have lamented, aren't what they used to be. In the old days, you see, you had to make your choices (or have them made for you by which class you had been born into and, in the light of this, what would get you camaraderie and what would get you beaten up), and stick with them. You were either a Mod or a Rocker, or a Punk or a Grebo or something, and you would live (and, in some cases, die) by that; you wore the uniform, listened to the music, and had little tolerance for other subcultures; if you fancied the other side's soundtrack or sartorial style, you would keep it to yourself, or else. But kids these days (kids these days...!) treat subculture as if it were a supermarket, or perhaps Noel Fielding's dressing-up chest; the entire back-catalogue of young cool is there for the taking and the mashing up, with elements going in and out of style by the season, to be worn as accessories. Beyond the dress-up element, the default becomes a globalised homogenate, a sort of international Brooklyn/Berlin/Harajuku of skinny jeans/folkbeards/vividly coloured sunglasses/patterned fabrics worn by the international Hipster, and, more intensely and urgently, by their adolescent precursor, the Scene Kid. Subcultural music, meanwhile, is a post-ironic soup of the last few decades of influences, refracted through the prisms of trend blogs (drum machines, hazy synths, skronky/choppy guitars, That Krautrock Drum Beat, and so on). Parties are inevitably called “raves”, whether or not they bear any similarity to MDMA-fuelled bacchanales around the M25 circa 1987. Increasingly, the content of the subculture becomes interchangeable, and the process of performing a subculture becomes the subculture; almost like a masked ball, or a postmodern reënactment society for the youth tribes of the 20th century.

But once one goes beyond the idea of a subculture as being based around fashion or music, things sometimes start to get much more unusual. One case in point is the Tulpamancy subculture; which, could be summed up in three words as “extreme imaginary friends”. Tulpamancers essentially invent imaginary friends and believe in them really hard, to the point of voluntarily inducing dissociative personalities in themselves, hiving off one part of their minds to be another, autonomous, personality, with whom they can interact.

The term tulpa is a Tibetan word meaning a sentient being created from pure thought; the practice crossed over from Tibetan mysticism into the Western occult/esoteric fringe in the early 20th century (the explorer Alexandra David-Neel was one pioneer), but the modern version owes more to internet “geek” subcultures; it started amongst Bronies (dudes who are really into My Little Pony, which may be either a repudiation of gender dichotomies or the ontological equivalent of a frat-bro panty raid on the idea of “girl”, or both or neither), before spreading to other branches of “geek” culture/fandom.

Tulpas remained the preserve of occultists until 2009, when the subject appeared on the discussion boards of 4chan. A few anonymous members started to experiment with creating tulpas. Things snowballed in 2012 when adult fans of My Little Pony: Friendship is Magic – known as “bronies” to anyone who's been near a computer for the past three years – caught on. They created a new forum on Reddit and crafted tulpas based on their favourite characters from the show.

In the cross-pollinating fields of the internet, it wasn’t long before tulpamancy also started to attract manga and fantasy fans. “My tulpa is called Jasmine,” says Ele. “She’s a human but from an alternative reality where she can do magic. I created her a dozen years ago for a fantasy series I write and then made her into a tulpa.”Being a fandom subculture, there are, of course, plenty of drawings (of varying levels of execution) depicting tulpas; one probably would not be too surprised to find that many look either like anime bishonen with fox ears/snouts and/or variants on Hot Topic Darkling. Because, of course, that's what one's magical alter-ego looks like in fandom.

As for the creation of, and interaction with, these tulpas, an entire methodology has evolved for bringing them into being, and interacting with them. Tulpamancers don't so much consciously think up their spirit critters, but rather mentally create a wonderland, imagine themselves in it, and let them come up from their subconscious and meet them. From then on, they practice imagining them, allowing them to become clearer, and ultimately being able to hallucinate them in everyday reality, which is where the fun starts:

While voice is the most common way tulpas communicate with their hosts, tulpamancers can learn to stroke their tulpa’s fur, feel their breath on their neck and even experience sexual contact.

Tulpas soon get curious about their host’s body; some want to experience life as a “meatperson”. Indulgent hosts then use a practice called “switching”, which allows their tulpa to possess their body while they watch from the ringside of consciousness.This, of course, sounds a lot like disassociative personality disorder, something not generally seen as desirable. Some tulpamancers, though, have turned that claim on its head; rather than dissociation being a disorder, or a symptom of one, what if it could be a way of self-medicating or coping What if, in other words, the optimal number of personalities in one body is, in some circumstance, greater than 1?

Koomer’s case is rare, and for Veissière “schizophrenia [could be understood as]… an incapacitating example of ‘involuntary Tulpas’", therefore, by forming positive relationships with their symptoms, sufferers can start to recover. It's an idea shared by the “Hearing Voices Movement”, who challenge the medical models of schizophrenia and suggest that pathologisation aggravates symptoms. “My schizophrenia manifested itself by having many thoughts and ideas all conflicting and shouting at me,” says Logan, who wanted his last name withheld. “Turning them into tulpas gave those thoughts a face and allowed them to be sorted out in a way that made sense.”

2014/6/30

In January 2012, Facebook conducted a psychology experiment on 689,003 unknowing users, modifying the stories they saw in their news feeds to see whether this affected their emotional state. The experiment was automatically performed over one week by randomly selecting users and randomly assigning them to two groups; one had items with positive words like “love” and “nice” filtered out of their news feeds, whereas the other had items with negative words similarly removed; the software then tracked the affect of their status updates to see whether this affected them. The result was that it did: a proportion of those who saw only positive and neutral posts tended to be more cheerful than those who saw only negative and neutral ones. (The experiment, it must be said, was entirely automated, with human researchers never seeing the users' identities or posts.)

Of course, this sort of experiment sounds colossally unethical, not to mention irresponsible. The potential adverse consequences are too easy to imagine, and too hard to comfortably dismiss. If some 345,000 people's feeds were modulated to feed them a week of negativity in the form of what they thought were their friends' updates, what proportion of those were adversely affected beyond feeling bummed out for a week? Out of 345,000, what would be the expected amount of relationship breakups, serious arguments, alcoholic relapses, or even incidents of self-harm that may have been set off by the online social world looking somewhat bleaker and more joyless? And while it may seem that the other cohort, who got a week's worth of sunshine and rainbows, were done a favour, this is not the case; riding the heady rush of good vibes, some of them may have made bad decisions; taking gambles on bad odds because they felt lucky, or dismissing warning signs of problems. And then there's the fact that messages from their friends and family members were deliberately not shown to them if they went against the goals of the experiment. What if someone in the negative cohort was cut off from communications with a loved one far away, for just long enough to introduce a grain of suspicion into their relationship, or someone in the positive cohort didn't learn about a close friend's problems and was unable to offer support?

In academe, this sort of thing would not pass an ethics committee, where informed consent is required. However, Facebook is not an academic operation, but a private entity operating in the mythical wild frontier of the Free Market, where anything both parties consent to (“consent” here being defined in the loosest sense) goes. And when you signed up for a Facebook account, you consented to them doing pretty much whatever they like with your personal information and the relationships mediated through their service. If you don't like it, that's fine; it's a free market, and you're welcome to delete your account go to Google Plus. Or if Google's ad-targeting and data mining don't appeal, to build your own service and persuade everyone you wish to keep in touch with to use it. (Except that you can't; these aren't the wild 1990s, when a student could build LiveJournal in his dorm room; nowadays, the legal liabilities and regulatory compliance requirements would keep anyone other than multinational corporations with deep pockets out of the game.) Or go back to emailing a handful of friends, in the hope that they'll reply to your emails in the spare time left over after keeping up with Facebook. Or only socialising with people who live within walking distance of the same pub as you. Or, for that matter, go full Kaczynski and live in a shack in the woods. And when you've had enough of trapping squirrels for your food and mumbling to yourself as you stare at the corner each night, you can slink back to the bright lights, tail between your legs, reconnect with Mr. Zuckerberg's Magical Social Casino, where all your friends are, and once again find yourself privy to sweet, sweet commercially-mediated social interaction. In the end, we all come back. We know that, in this age, the alternative is self-imposed exile and social death, and so does Facebook, so they can do what they like to us.

As novel as this may seem, this is another instance of the neoliberal settlement, tearing up prior settlements and regulations in favour of a flat, market-based system, rationalised by a wilful refusal to even consider the disparities of power dynamics (“there is no such thing as an unfair deal in a free market, because you can always walk away and take a better offer from one of the ∞ other competitors”, goes the argument taken to its platygæan conclusion). Just as in deregulated economies, classes of participants (students, patients, passengers) all become customers, with their roles and rights replaced by what the Invisible Hand Of The Free Market deals out (i.e., what the providers can get away with them acquiescing to when squeezed hard enough), here those using a means of communication become involuntary guinea pigs in a disruptive, and (for half of them) literally unpleasant experiment. All that Facebook has to provide, in theory, is something marginally better than social isolation, and everything is, by definition, as fair as can be.

Facebook have offered an explanation, saying that the experiment was intended to “make the content people see as relevant and engaging as possible”. Which, given the legendarily opaque Facebook feed algorithm, and how it determines which of your friends' posts get a look into the precious spaces between the ads and sponsored posts, is small comfort. Tell you what, Facebook: why don't you stop trying to make my feed more “relevant” and “engaging” and just give me what my friends, acquaintances and groups post, unfiltered and in chronological order, and let me filter it as I see fit?

2014/2/14

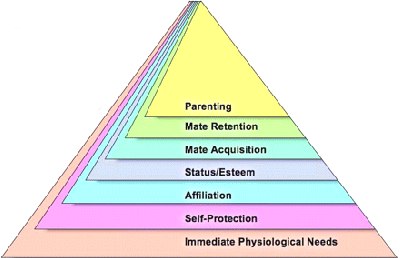

The ascent up the Maslow hierarchy of needs might have a dark side; a US psychologist claims that the ideal of self-actualisation has created a world in which romantic relationships are more likely to fail. Eli Finkel of Northwestern University posits the “suffocation” model of marriage, asserts that, as the needs we have of a partner have changed from shared survival in a hostile environment, through romantic love and onto mutual self-discovery, and the time these couples spend with one another decreases due to external time constraints, it is harder for any actual relationship with another human being (especially one who also wishes to discover themselves) to fit the bill:

"People used to marry for basic things like food and shelter. In the 1800s, you didn't have to have profound insight into your partner's core essence to tend to the chickens or build a sound physical structure against the snow," Finkel said. "Back then, the idea of marrying for love was ludicrous."

"In 2014, you are really hoping that your partner can help you on a voyage of discovery and personal growth, but your partner cannot do that unless he or she really knows who you are, and really understands your core essence. That requires much greater investment of time and psychological resources," he said.

2013/10/19

Book of Lamentations, a review of the American Psychological Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition as a work of dystopian literature:

If the novel has an overbearing literary influence, it’s undoubtedly Jorge Luis Borges. The American Psychiatric Association takes his technique of lifting quotes from or writing faux-serious reviews for entirely imagined books and pushes it to the limit: Here, we have an entire book, something that purports to be a kind of encyclopedia of madness, a Library of Babel for the mind, containing everything that can possibly be wrong with a human being. Perhaps as an attempt to ward off the uncommitted reader, the novel begins with a lengthy account of the system of classifications used – one with an obvious debt to the Borgesian Celestial Emporium of Benevolent Knowledge, in which animals are exhaustively classified according to such sets as “those belonging to the Emperor,” “those that, at a distance, resemble flies,” and “those that are included in this classification.”

As you read, you slowly grow aware that the book’s real object of fascination isn’t the various sicknesses described in its pages, but the sickness inherent in their arrangement... This mad project is clearly something that its authors are fixated on to a somewhat unreasonable extent. In a retrospectively predictable ironic twist, this precise tendency is outlined in the book itself. The entry for obsessive-compulsive disorder with poor insight describes this taxonomical obsession in deadpan tones: “repetitive behavior, the goal of which is […] to prevent some dreaded event or situation.” Our narrator seems to believe that by compiling an exhaustive list of everything that might go askew in the human mind, this wrong state might somehow be overcome or averted. References to compulsive behavior throughout the book repeatedly refer to the “fear of dirt in someone with an obsession about contamination.” The tragic clincher comes when we’re told, “the individual does not recognize that the obsessions or compulsions are excessive or unreasonable.” This mad project is so overwhelming that its originator can’t even tell that they’ve subsumed themselves within its matrix. We’re dealing with a truly unreliable narrator here, not one that misleads us about the course of events (the narrator is compulsive, they do have poor insight), but one whose entire conceptual framework is radically off-kilter. As such, the entire story is a portrait of the narrator’s own particular madness. With this realization, DSM-5 starts to enter the realm of the properly dystopian.

2013/9/18

Builders of Star Trek-inspired rooms recently in the news: a convicted paedophile (or, to be precise, another one, though his Star Trek-inspired flat has been in the news previously), and the US National Security Agency.

2013/2/23

A behavioural economist from Yale has posited the theory that how one's primary language handles the future tense influences the amount of planning one does for the future, with one consequence being that English speakers save less for their old age than speakers of languages such as Mandarin and Yoruba, which lack a separate future tense and instead treat the future as part of the present. Professor Keith Chen's theory is that, in doing so, such languages encourage and entrench habits of thought more conducive to mindfulness of one's future than languages where the future is hived off into a separate grammatical tense:

Prof Chen divides the world's languages into two groups, depending on how they treat the concept of time. Strong future-time reference languages (strong FTR) require their speakers to use a different tense when speaking of the future. Weak future-time reference (weak FTR) languages do not.

"The act of savings is fundamentally about understanding that your future self - the person you're saving for - is in some sense equivalent to your present self," Prof Chen told the BBC's Business Daily. "If your language separates the future and the present in its grammar that seems to lead you to slightly disassociate the future from the present every time you speak.The effect is not limited to exotic non-European languages; similar differences are present in European languages to an extent (for example, one often uses the present tense in German to refer to events in the future, which is not the case in English, French or Italian; whether this has any causal relationship with the higher rate of personal saving in Germany remains to be determined).

Professor Chen's paper, The Effect of Language on Economic Behavior: Evidence from Savings Rates, Health Behaviors, and Retirement Assets, is (here), in PDF format.

If this effect holds true, all may not be lost; one could consciously intervene in English to an extent without breaking too much, by forcing oneself to say things like “I'm going to the seminar” rather than “I will go to the seminar”. Further flattenings-out of the future tense, however, get more awkward; saying, at age 29, “I'm retiring to the south of France” could raise a few eyebrows.

2012/6/13

Researchers in the US have been investigating the question of what is “cool” from a psychological perspective, hitting the dichotomy between the two opposite poles which can be described with this term: on one hand, agreeability and popularity, and, on the other hand, a vaguely antisocial countercultural/oppositional stance reflected in the classic iconography of rebels and outlaws from the history of cool:

"I got my first sunglasses when I was about 13," said Dar-Nimrod. "There wasn't a cooler kid on the block for the next few days. I was looking cool because I was distant from people. My emotions were not something they could read. I put a filter between me and everyone else. That, in my mind, made me cool. Today, that doesn't seem to be supported. If anything, sociability is considered to be cool, being nice is considered to be cool. And in an oxymoron, being passionate is considered to be cool—at least, it is part of the dominant perception of what coolness is. How can you combine the idea of cool—emotionally controlled and distant—with passionate?"

"We have a kind of a schizophrenic coolness concept in our mind," Dar-Nimrod said. "Almost any one of us will be cool in some people's eyes, which suggests the idiosyncratic way coolness is evaluated. But some will be judged as cool in many people's eyes, which suggests there is a core valuation to coolness, and today that does not seem to be the historical nature of cool. We suggest there is some transition from the countercultural cool to a generic version of it's good and I like it. But this transition is by no way completed."The researchers claim that the concept of “cool” is mutating away from the oppositional/rebellious sense and towards straight agreeability.

If this phenomenon does bear itself out, there may be a number of possible explanations. Perhaps, as the countercultural struggles against the repressive hegemony of the “squares” have receded into folk memory of The Fifties and everyone wears jeans, listens to rock and has smoked a joint at least once in their lives, the idea of the rebel is left with even less of a cause than before Perhaps the shift in the meaning of “cool” has something to do with the ongoing process of commodification of the counterculture, with the sneers and icy glares of vintage cool now being little more than a mask for agreeable dudes to put on when the occasion suits. Or perhaps, in the information age, being agreeable and well-connected confers a greater advantage than being tough and detached. One would imagine that this would be the case in most normal situations, in which case, the old world of tough guys and strong, silent types would have been an anomalous case, a hostile environment which traumatised its inhabitants into growing expensive carapaces of character armour.

Another option would be that the meaning of “cool” is not, in fact, changing (this study doesn't seem to involve surveys done decades earlier to gauge what people thought at the time, and compares living attitudes with canned stereotypes), and that the word “cool” has several meanings; when it's used as a term of approval for a person, it has always indicated agreeability, whereas when talking about fictional characters, it suggested a certain type of antiheroic asshole.

2012/5/26

A study of user questionnaires on the site yourmorals.org (whose stated goal is “to understand the way our "moral minds" work”) suggests a truth about the nature of the left-right political divide: that levels of empathy are positively correlated with political engagement among liberals, and negatively among conservatives. (This is a study in the US, hence the terminology.)

2012/5/4

Cracked's David Wong has a list of five telltale indicators of a bullshit political story; in this case, a “bullshit political story” is one which ignores the actual issues and treats politics as a sporting event, appealing to the audience's identification with one team or other:

The answer is that many (if not most) people don't follow politics in order to find out who to vote for as part of their duty as citizens living in a democracy. They follow it purely as a form of entertainment. They're like sports fans, rooting for their "team" to win. And as you're going to find out, virtually all political news coverage is written to appeal to those people. They're the most rabid "consumers" of news, and their traffic is the most reliable, so the news is tailored to appeal to them. In the business, they derisively call it "horse race journalism," where the stories focus purely on the "sport" of politics rather than the consequences.The telltale signs are stories with the word “gaffe” in the headline (generally some content-free event giving one half of the stadium cause to hoot and jeer at what dumbasses the other side are), anything about a politician “blasting” the other side (which appeals to the audience's inner wrestling fan), weasel-worded headlines asking a question (the answer to which is generally “probably not”), headlines attempting to escalate random low-ranking members of one political side, generally with non-mainstream opinions, to the status of “lawmakers” or “advisors” and demanding that the leadership take responsibility for them, and real-world political issues being framed as a “blow to” one political side or other:

That's where the gaffe stories come in. See, in this game, your "team" scores a point each time the other team says something stupid. It lets all of the supporters of your team mock and humiliate the supporters of the opposing team, on Internet message boards and around water coolers and in coffee shops nationwide. "Haha! The supposed 'genius' Obama thinks there are 57 states in the U.S.!" "Oh, yeah? Well, your last president said he was going to help terrorists plan their next attack!"

Hey, did you know that Barack Obama is an out-of-touch elitist because he puts fancy Dijon mustard on his hamburgers? Did you know that Mitt Romney is an insane sociopath because he once made his pet dog ride on top of his car 26 years ago? Did you know John Kerry can't relate to the average person because he puts Swiss cheese on his Philly cheese steaks? Did you know that George W. Bush hates foreigners so much that he wiped his hand after shaking hands with a Haitian? Did you know that all of this is petty schoolyard bullshit that wastes valuable time and energy that you'll never get back?

And, as smarter commentators have pointed out, there's an even bigger problem with this: It actually implies that the issue itself is completely unimportant. For instance, if the courts overturn some regulation about mercury in the water or Congress blocks car mileage standards, it always gets reported as "A Blow to Environmentalists." Oh, no, it's not a blow to the people who have to drink the water or breathe the air, or the taxpayers who have to fund the regulations, or the businesses that lose jobs over it. It's either a "blow to environmentalists" or it's not. They specifically make it sound like the effects extend purely to some fringe special interest group and absolutely no one else.

I'm telling you from experience, watching political races this way is addictive as shit. You have thousands of years of violent tribal instincts pumping through your veins, itching for a fight. That makes you an easy tool for manipulation, and every good politician and pundit knows how to push those buttons to make people march neatly in formation. Don't succumb. Or else you'll start supporting the most bullshit legislation just because your guy is for it. Or you'll start knee-jerk rejecting anything the other "team" proposes. Not because it's bad for the country, but because you want to deny them a "win."

2012/3/8

When testing drugs for treating depression on lab mice, it is important to have ways of determining whether or not a mouse is depressed, or suffering from the mouse equivalent of depression. Not surprisingly, mice deemed to be depressed are the ones which give up and stop struggling when faced with difficulty, and which get little joy from life:

Forced swimming test. The rat or mouse is placed into a cylinder partially filled with water from which escape is difficult. The longer it swims, the more actively it is trying to escape; if it stops swimming, this cessation is interpreted as depressionlike behavior, a kind of animal fatalism.

Sugar water preference. The preference an animal shows for sugar water is taken as an indication of its ability to derive pleasure, a quality that is missing in depression. Most rodents, when given two identical-looking sources of water, will drink much more of the sweetened water than the plain water. Rodents exposed to chronic stress or whose brains have been manipulated show no such preference.(Previously: Scientists create a mouse that's permanently happy.)

(via Boing Boing) ¶ 0

2012/3/7

Apropos of the previous post, a few tidbits from research on what information one can determine from someone's Facebook profile, without even looking at their activity:

People who tested as "extroverts" on the personality test tended to have more friends, but their networks tended to be more sparse, meaning that they made friends with lots of different people who are less likely to know each other.

The researchers also found that people with long last names tended to be more neurotic, perhaps because "a lifetime of having one's long last name misspelled may lead to a person expressing more anxiety and quickness to anger," according to the study, which is being presented this week at the Computer Human Interaction conference in Vancouver.

2012/3/4

Psychologist Bruce Levine makes the claim that, in the US, the psychological profession has a bias towards conformism and authoritarianism, and against anti-authoritarian tendencies. This bias apparently results from the institutional structure of the profession, which selects for and reinforces pro-conformist and pro-authoritarian tendencies, and manifests itself, among other things, in those who exhibit “anti-authoritarian tendencies” being caught, diagnosed with various mental illnesses and medicated into compliance before they can develop into actual troublemakers:

In my career as a psychologist, I have talked with hundreds of people previously diagnosed by other professionals with oppositional defiant disorder, attention deficit hyperactive disorder, anxiety disorder and other psychiatric illnesses, and I am struck by (1) how many of those diagnosed are essentially anti-authoritarians, and (2) how those professionals who have diagnosed them are not.

Anti-authoritarians question whether an authority is a legitimate one before taking that authority seriously. Evaluating the legitimacy of authorities includes assessing whether or not authorities actually know what they are talking about, are honest, and care about those people who are respecting their authority. And when anti-authoritarians assess an authority to be illegitimate, they challenge and resist that authority—sometimes aggressively and sometimes passive-aggressively, sometimes wisely and sometimes not.

Some activists lament how few anti-authoritarians there appear to be in the United States. One reason could be that many natural anti-authoritarians are now psychopathologized and medicated before they achieve political consciousness of society’s most oppressive authorities.Showing hostility to or resentment of authority will get one diagnosed with various conditions, such as “opposition defiant disorder (ODD)”, a condition which manifests itself in deficits in “rule-governed behaviour”, and for which, as for many parts of the human condition, there are many types of corrective medication these days. (Compare this to the condition of “sluggish schizophrenia”, which only existed in the Soviet Union and manifested itself as a rejection of the self-evident truth of Marxism-Leninism.)

While pretty much every hierarchical society has mechanisms for encouraging conformity to some degree, Dr. Levine's contention is that the increase in psychiatric medication in recent years may be leading to a more authoritarian and conformistic society.

2012/2/27

Stage magician Teller explains some of the cognitive principles behind the magician's craft:

1. Exploit pattern recognition. I magically produce four silver dollars, one at a time, with the back of my hand toward you. Then I allow you to see the palm of my hand empty before a fifth coin appears. As Homo sapiens, you grasp the pattern, and take away the impression that I produced all five coins from a hand whose palm was empty.

2. Make the secret a lot more trouble than the trick seems worth. You will be fooled by a trick if it involves more time, money and practice than you (or any other sane onlooker) would be willing to invest. My partner, Penn, and I once produced 500 live cockroaches from a top hat on the desk of talk-show host David Letterman. To prepare this took weeks. We hired an entomologist who provided slow-moving, camera-friendly cockroaches (the kind from under your stove don’t hang around for close-ups) and taught us to pick the bugs up without screaming like preadolescent girls. Then we built a secret compartment out of foam-core (one of the few materials cockroaches can’t cling to) and worked out a devious routine for sneaking the compartment into the hat. More trouble than the trick was worth? To you, probably. But not to magicians.

3. It’s hard to think critically if you’re laughing. We often follow a secret move immediately with a joke. A viewer has only so much attention to give, and if he’s laughing, his mind is too busy with the joke to backtrack rationally.

2012/2/18

The New York Times has a fascinating article about how retail companies use data mining and carefully targeted coupons to analyse and influence the spending habits of consumers, without the consumers getting wise to what's happening and resisting:

Almost every major retailer, from grocery chains to investment banks to the U.S. Postal Service, has a “predictive analytics” department devoted to understanding not just consumers’ shopping habits but also their personal habits, so as to more efficiently market to them. “But Target has always been one of the smartest at this,” says Eric Siegel, a consultant and the chairman of a conference called Predictive Analytics World. “We’re living through a golden age of behavioral research. It’s amazing how much we can figure out about how people think now.”A specific case the article describes is that of finding new parents-to-be, who will soon be in a position of having to form new spending habits, and doing so before the competition can identify them from public information; which is to say, inferring from statistical information whether a customer is likely to be pregnant, and at which stage, and then subtly manipulating her spending through the various milestones of her child's development:

The only problem is that identifying pregnant customers is harder than it sounds. Target has a baby-shower registry, and Pole started there, observing how shopping habits changed as a woman approached her due date, which women on the registry had willingly disclosed. He ran test after test, analyzing the data, and before long some useful patterns emerged. Lotions, for example. Lots of people buy lotion, but one of Pole’s colleagues noticed that women on the baby registry were buying larger quantities of unscented lotion around the beginning of their second trimester. Another analyst noted that sometime in the first 20 weeks, pregnant women loaded up on supplements like calcium, magnesium and zinc. Many shoppers purchase soap and cotton balls, but when someone suddenly starts buying lots of scent-free soap and extra-big bags of cotton balls, in addition to hand sanitizers and washcloths, it signals they could be getting close to their delivery date.

One Target employee I spoke to provided a hypothetical example. Take a fictional Target shopper named Jenny Ward, who is 23, lives in Atlanta and in March bought cocoa-butter lotion, a purse large enough to double as a diaper bag, zinc and magnesium supplements and a bright blue rug. There’s, say, an 87 percent chance that she’s pregnant and that her delivery date is sometime in late August. What’s more, because of the data attached to her Guest ID number, Target knows how to trigger Jenny’s habits. They know that if she receives a coupon via e-mail, it will most likely cue her to buy online. They know that if she receives an ad in the mail on Friday, she frequently uses it on a weekend trip to the store. And they know that if they reward her with a printed receipt that entitles her to a free cup of Starbucks coffee, she’ll use it when she comes back again.The uncanny accuracy of the algorithm is demonstrated by an anecdote about an angry father storming into a Target store demanding why they had sent his teenaged daughter coupons for nappies and prams, and then, some time later, returning to apologise, having discovered that she had, in fact, become pregnant.

Of course, there is the small issue of how to use this wealth of information in a plausibly deniable sense, without being obviously creepy. People, after all, tend to react badly to being surreptitiously watched and manipulated, especially so when deeply personal matters are involved:

“With the pregnancy products, though, we learned that some women react badly,” the executive said. “Then we started mixing in all these ads for things we knew pregnant women would never buy, so the baby ads looked random. We’d put an ad for a lawn mower next to diapers. We’d put a coupon for wineglasses next to infant clothes. That way, it looked like all the products were chosen by chance. And we found out that as long as a pregnant woman thinks she hasn’t been spied on, she’ll use the coupons. She just assumes that everyone else on her block got the same mailer for diapers and cribs. As long as we don’t spook her, it works.”

2012/2/4

In 1995, the state legislature of New Mexico passed a law requiring psychologists and psychiatrists to be dressed as wizards when giving evidence in court:

When a psychologist or psychiatrist testifies during a defendant’s competency hearing, the psychologist or psychiatrist shall wear a cone-shaped hat that is not less than two feet tall. The surface of the hat shall be imprinted with stars and lightning bolts. Additionally, a psychologist or psychiatrist shall be required to don a white beard that is not less than 18 inches in length, and shall punctuate crucial elements of his testimony by stabbing the air with a wand. Whenever a psychologist or psychiatrist provides expert testimony regarding a defendant’s competency, the bailiff shall contemporaneously dim the courtroom lights and administer two strikes to a Chinese gong…The amendment passed unanimously, but was removed from the final law, to the detriment of the theatrical beard and Chinese gong industries.

2012/1/29

Idea of the day: the Happy Recession; the idea that the internet, through driving prices and costs down, will permanently deflate both prices and wages; the post-internet world, it seems, jams econo:

The most pernicious aspect of Internet entertainment is that it’s so easy to measure and so easy to mass-produce. So the moment something on the Internet gets fun enough to be competitive with the real-world analogue, it starts getting relentlessly improved until it’s vastly superior. World of Warcraft soaks up upwards of forty hours per week from serious fans, who pay about $15 per month for their subscriptions. Few other hobbies can consume so much time at such a low cost.

The web makes it easier to access non-traditional employees at much lower salaries. As we argued in our Demand Media analysis, the real story here is that a stay-at-home mom with a Masters in Journalism can write content that is good enough compared to a typical Madison Avenue copywriter, especially when the rate is $15 per article instead of six figures per year. This disaggregation of writing skill means that companies no longer have to hire good writers in order to write 5% good copy and 95% mediocre work; they can outsource the mediocre stuff and relegate the high-end work to a short-term freelancer.

The web offers cheap social status: In the long term, this may have a bigger effect than the web merely making digitizable products cheaper. Social status games drive a huge amount of economic activity: people strive to get into high-paying, high prestige career tracks, to win promotions and attendant raises, to live in the best neighborhoods and send their kids to the best schools. Few status games lack some kind of economic output—people who play sports well below the professional level still get some job opportunities out of it.One could probably also add a geographical factor to this: in the age of cheap, ubiquitous opportunity, access to economic and cultural opportunities is less dependant on being located in a buzzing metropolis or creative-class hive; after all, if a copywriter or app developer can work from anywhere with creativity, things like music and art scenes (or whatever replaces the post-punk rock'n'roll era construction of the "music scene" in the cultural ecosystem) are centred around blogs rather than physical venues, and one doesn't even need to move to a different place to find like-minded people, there would be less competition for living in more desirable areas, when the price of not doing so no longer includes disconnection from as many opportunities.

2012/1/19

The street financial sector finds its own uses for things psychopath profiling tests:

My companion, a senior UK investment banker and I, are discussing the most successful banking types we know and what makes them tick. I argue that they often conform to the characteristics displayed by social psychopaths. To my surprise, my friend agrees.

He then makes an astonishing confession: "At one major investment bank for which I worked, we used psychometric testing to recruit social psychopaths because their characteristics exactly suited them to senior corporate finance roles."

Here was one of the biggest investment banks in the world seeking psychopaths as recruits.

2011/11/10

Writing in the Pinboard blog, Maciej Ceglowski tears apart the concept "social graph", saying that it is neither social nor a graph, but a sort of pseudoscience invented by socially-challenged geeks and now peddled by hucksters out to monetise you and your relationships:

Last week Forbes even went to the extent of calling the social graph an exploitable resource comprarable to crude oil, with riches to those who figure out how to mine it and refine it. I think this is a fascinating metaphor. If the social graph is crude oil, doesn't that make our friends and colleagues the little animals that get crushed and buried underground?The first part of his argument has to do with the inadequacy of the "social graph" model for representing all the nuances of human social relationships in the real world; the many gradations of friendship and acquaintance, the ways relationships change and evolve, making a mockery of nailed-down static representations; the way that describing a relationship can change it in some cases, and various issues of privacy and multi-faceted identity, things which exist trivially in the real world, even if they're in violation of the Zuckerberg Doctrine.

One big sticking point is privacy. Do I really want to find out that my pastor and I share the same dominatrix? If not, then who is going to be in charge of maintaining all the access control lists for every node and edge so that some information is not shared? You can either have a decentralized, communally owned social graph (like Fitzpatrick envisioned) or good privacy controls, but not the two together.

This obsession with modeling has led us into a social version of the Uncanny Valley, that weird phenomenon from computer graphics where the more faithfully you try to represent something human, the creepier it becomes. As the model becomes more expressive, we really start to notice the places where it fails.

You might almost think that the whole scheme had been cooked up by a bunch of hyperintelligent but hopelessly socially naive people, and you would not be wrong. Asking computer nerds to design social software is a little bit like hiring a Mormon bartender. Our industry abounds in people for whom social interaction has always been more of a puzzle to be reverse-engineered than a good time to be had, and the result is these vaguely Martian protocols.Of course, whilst the idea of the social graph may not be good for modelling real-life social interactions with naturalistic fidelity, it has been a boon for targeting advertising; the illusion of social fulfilment is enough to keep people clicking and volunteering information about themselves. From the advertisers' point of view, the fish not only jump right into the boat, they fillet themselves in mid-air and bring their own wedges of lemon:

Imagine the U.S. Census as conducted by direct marketers - that's the social graph. Social networks exist to sell you crap. The icky feeling you get when your friend starts to talk to you about Amway, or when you spot someone passing out business cards at a birthday party, is the entire driving force behind a site like Facebook.There is some good news, though: while general-purpose social web sites with the ambition of mediating (and monetising) the entirety of human social interaction may fail creepily as they approach their goal, special-purpose online communities can thrive in their niches:

The funny thing is, no one's really hiding the secret of how to make awesome online communities. Give people something cool to do and a way to talk to each other, moderate a little bit, and your job is done. Games like Eve Online or WoW have developed entire economies on top of what's basically a message board. MetaFilter, Reddit, LiveJournal and SA all started with a couple of buttons and a textfield and have produced some fascinating subcultures. And maybe the purest (!) example is 4chan, a Lord of the Flies community that invents all the stuff you end up sharing elsewhere: image macros, copypasta, rage comics, the lolrus. The data model for 4chan is three fields long - image, timestamp, text. Now tell me one bit of original culture that's ever come out of Facebook.I wonder whether there is a dichotomy there between sites and networks; would a special-interest site that used, say, Facebook's social graph as a means of identifying users (rather than having its own system of accounts, usernames, profiles, and optionally friendship/trust edges) be infected by the Zuckerbergian malaise?

2011/8/10

In the wake of riots across the UK, the BBC asks what turns ordinary people into looters:

Psychologists argue that a person loses their moral identity in a large group, and empathy and guilt - the qualities that stop us behaving like criminals - are corroded. "Morality is inversely proportional to the number of observers. When you have a large group that's relatively anonymous, you can essentially do anything you like," according to Dr James Thompson, honorary senior lecturer in psychology at University College London.

He rejects the notion that some of the looters are passively going with the flow once the violence has taken place, insisting there is always a choice to be made.

Workman argues that some of those taking part may adopt an ad hoc moral code in their minds - "these rich people have things I don't have so it's only right that I take it". But there's evidence to suggest that gang leaders tend to have psychopathic tendencies, he says.

[Criminologist Prof. John Pitts] says most of the rioters are from poor estates who have no "stake in conformity", who have nothing to lose. "They have no career to think about. They are not 'us'. They live out there on the margins, enraged, disappointed, capable of doing some awful things."

2011/6/28

Today in weaponised sociolinguistics: the US intelligence research agency IARPA is running a programme to collect and catalogue metaphors used in different cultures, hopefully revealing how the Other thinks. This follows on from the work of cognitive linguist George Lakoff, who theorised that whoever controls the metaphors used in language can tilt the playing field extensively:

Conceptual metaphors have been big business over the last few years. During the last Bush administration, Lakoff – a Democrat – set up the Rockridge Institute, a foundation that sought to reclaim metaphor as a tool of political communication from the right. The Republicans, he argued, had successfully set the terms of the national conversation by the way they framed their metaphors, in talking about the danger of ‘surrendering’ to terrorism or to the ‘wave’ of ‘illegal immigrants’. Not every Democrat agreed with his diagnosis that the central problem with American politics was that it was governed by the frame of the family, that conservatives were proponents of ‘authoritarian strict-father families’ while progressives reflected a ‘nurturant parent model, which values freedom, opportunity and community building’ (‘psychobabble’ was one verdict, ‘hooey’ another).

But there’s precious little evidence that they tell you what people think. One Lakoff-inspired study that at first glance resembles the Metaphor Program was carried out in the mid-1990s by Richard D. Anderson, a political scientist and Sovietologist at UCLA, who compared Brezhnev-era speeches by Politburo members with ‘transitional’ speeches made in 1989 and with post-1991 texts by post-Soviet politicians. He found, conclusively, that in the three periods of his study the metaphors used had changed entirely: ‘metaphors of personal superiority’, ‘metaphors of distance’, ‘metaphors of subordination’ were out; ‘metaphors of equality’ and ‘metaphors of choice’ were in. There was a measurable change in the prevailing metaphors that reflected the changing political situation. He concluded that ‘the change in Russian political discourse has been such as to promote the emergence of democracy’, that – in essence – the metaphors both revealed and enabled a change in thinking. On the other hand, he could more sensibly have concluded that the political system had changed and therefore the metaphors had to change too, because if a politician isn’t aware of what metaphors he’s using who is?The article is vague on the actual IARPA research programme, but reveals that it involves extracting metaphors from large bodies of texts in four languages (Farsi, Mexican Spanish, Russian and English) and classifying them according to emotional affect.

The IARPA metaphor programme follows an earlier proposal to weaponise irony:

If we don’t know how irony works and we don’t know how it is used by the enemy, we cannot identify it. As a result, we cannot take appropriate steps to neutralize ironizing threat postures. This fundamental problem is compounded by the enormous diversity of ironic modes in different world cultures and languages. Without the ability to detect and localize irony consistently, intelligence agents and agencies are likely to lose valuable time and resources pursuing chimerical leads and to overlook actionable instances of insolence. The first step toward addressing this situation is a multilingual, collaborative, and collative initiative that will generate an encyclopedic global inventory of ironic modalities and strategies. More than a handbook or field guide, the work product of this effort will take the shape of a vast, searchable, networked database of all known ironies. Making use of a sophisticated analytic markup language, this “Ironic Cloud” will be navigable by means of specific ironic tropes (e.g., litotes, hyperbole, innuendo, etc.), by geographical region or language field (e.g., Iran, North Korea, Mandarin Chinese, Davos, etc.), as well as by specific keywords (e.g., nose, jet ski, liberal arts, Hermès, night soil, etc.) By means of constantly reweighted nodal linkages, the Ironic Cloud will be to some extent self-organizing in real time and thus capable of signaling large-scale realignments in the “weather” of global irony as well as providing early warnings concerning the irruption of idiosyncratic ironic microclimates in particular locations—potential indications of geopolitical, economic, or cultural hot spots.The proposal goes on to suggest possibilities of using irony as a weapon:

Superpower-level political entities (e.g., Roman Empire, George W. Bush, large corporations, etc.) have tended to look on irony as a “weapon of the weak” and thus adopted a primarily defensive posture in the face of ironic assault. But a historically sensitive consideration of major strategic realignments suggests that many critical inflection points in geopolitics (e.g., Second Punic War, American Revolution, etc.) have involved the tactical redeployment of “guerrilla” techniques and tools by regional hegemons. There is reason to think that irony, properly concentrated and effectively mobilized, might well become a very powerful armament on the “battlefield of the future,” serving as a nonlethal—or even lethal—sidearm in the hands of human fighters in an information-intensive projection of awesome force. Without further fundamental research into the neurological and psychological basis of irony, it is difficult to say for certain how such systems might work, but the general mechanism is clear enough: irony manifestly involves a sudden and profound “doubling” of the inner life of the human subject. The ironizer no longer maintains an integrated and holistic perspective on the topic at hand but rather experiences something like a small tear in the consciousness, whereby the overt and covert meanings of a given text or expression are sundered. We do not now know just how far this tear could be opened—and we do not understand what the possible vital consequences might be.

2011/6/24

A new study has shown that violent video games decrease crime rates. While they do increase aggression in the players, the incapacitation effect of the players being drawn into sitting in front of a computer or console for extended periods of time, and thus unlikely to attack anything larger than a plate of nachos in reality, outweighs this.

2011/6/14

Cognitive bias of the day: the name letter effect, which causes people to be subconsciously more favourably inclined to names and words that sound like their name:

The researchers then moved on to career choices. They combed the records of the American Dental Association and the American Bar association looking for people named either Dennis, Denice, Dena, Denver, et cetera, or Lawrence, Larry, Laura, Lauren, et cetera. That is: were there more dentists named Dennis and lawyers named Lawrence than vice versa? Of the various statistical analyses they performed, most said yes, some at < .001 level. Other studies determined that there was a suspicious surplus of geologists named Geoffrey, and that hardware store owners were more likely to have names starting with 'H' compared to roofing store owners, who were more likely to have names starting with 'R'.

Some other miscellaneous findings: people are more likely to donate to Presidential candidates whose names begin with the same letter as their own, people are more likely to marry spouses whose names begin with the same letter as their own, that women are more likely to show name preference effects than men (but why?), and that batters with names beginning in 'K' are more likely than others to strike out (strikeouts being symbolized by a 'K' on the records).

2011/5/25

Jon Ronson looks at what makes psychopaths tick:

I met an American CEO, Al Dunlap, formerly of the Sunbeam Corporation, who redefined a great many of the psychopath traits to me as "business positives": Grandiose sense of self-worth? "You've got to believe in yourself." (As he told me this, he was standing underneath a giant oil painting of himself.) Cunning/manipulative? "That's leadership."

I wondered if sometimes the difference between a psychopath in Broadmoor and a psychopath on Wall Street was the luck of being born into a stable, rich family.The article, which is excerpted from Ronson's new book, "The Psychopath Test", also follows the story of Tony, a youth who, when tried for a violent crime, feigned insanity in an attempt to avoid prison, and instead was diagnosed as a manipulative psychopath and committed to the notorious Broadmoor prison. After 12 years amongst notorious killers and the criminally insane, he secured a hearing, which found him, whilst mildly psychopathic, fit to be released into society:

"The thing is, Jon," Tony said as I looked up from the papers, "what you've got to realise is, everyone is a bit psychopathic. You are. I am." He paused. "Well, obviously I am," he said.

"What will you do now?" I asked.

"Maybe move to Belgium," he said. "There's this woman I fancy. But she's married. I'll have to get her divorced."

2011/4/4

Science blogger Ben Goldacre points us to an interesting psychology paper (unfortunately paywalled), analysing changes over the past few decades in the subject matter of popular song lyrics:

The current research fills this gap by testing the hypothesis that one cultural product—word use in popular song lyrics—changes over time in harmony with cultural changes in individualistic traits. Linguistic analyses of the most popular songs from 1980–2007 demonstrated changes in word use that mirror psychological change. Over time, use of words related to self-focus and antisocial behavior increased, whereas words related to other-focus, social interactions, and positive emotion decreased. These findings offer novel evidence regarding the need to investigate how changes in the tangible artifacts of the sociocultural environment can provide a window into understanding cultural changes in psychological processes.Compare and contrast: Hypebot's analysis of 2010 commercial pop lyrics, coming up with an example of perfectly generic pop lyrics, circa 2010:

Oh baby, yeah, Imma rock your body hard—like damnI wonder how much of this is actually emblematic of a deeper cultural shift towards short-term values. A world in which everything is a dynamic market of novelty and possibility, and "love" just means a temporary arrangement for mutually negotiated gratification.

Chick I wanna know, cause I get around now—like bad

Love gonna stop, Imma rock your body hard—like damn

Had enough tonight, I wanna break the love—like bad

2011/3/24

Scientists in China have found that mice bred to not be receptive to serotonin have no sexual preferences for either sex:

When presented with a choice of partners, they showed no overall preference for either males or females. When just a male was introduced into the cage, the modified males were far more likely to mount the male and emit a "mating call" normally given off when encountering females than unmodified males were.

However, a preference for females could be "restored" by injecting serotonin into the brain.The researchers have cautioned against drawing conclusions about human sexuality from the result.

The lazy takeaway from this, as seen in news sites, is that serotonin affects sexual orientation, with the suggestion that low serotonin might be the secret to the inexplicable condition known as homosexuality. I'm wondering whether a more plausible conclusion is that, with sexual selection being about competition amongst fit individuals, a prerequisite for having an active sexual preference is passing an internal test of subjective fitness, i.e., being aware that one has sufficiently high status to be picky. In other words, mice without functioning serotonin receptors perceive themselves as losers who will take anything that's warm and regard it, being more than they're entitled to, as a win.

2011/3/6

The Hathaway Effect: an observation that when Hollywood celebrity Anne Hathaway makes headlines, stock in Berkshire Hathaway, Warren Buffett's company, rises, for no other reason. Is it a demonstration of human irrationality (significant numbers of investors getting a good feeling about a stock by virtue of having its name in their mind for an unconnected reason), or, as the article suggests, automated trading systems picking up entertainment headlines and buying stock on the basis of them?

(via Boing Boing) ¶ 0

2011/1/29

Positivity considered harmful (2): A new study suggests that social software such as Facebook may be making its users unhappy, by causing them to overestimate how contented their peers are with their lives (unlike themselves). The theory goes that, as these sites are self-curated experiences where users present generally positive images of themselves, other users don't get well-rounded views of how an online acquaintance's life is going, but have a cognitive bias to thinking that they do. Consequently, we overestimate our online acquaintances' life satisfaction, compare it to our own, and feel unhappy:

The human habit of overestimating other people's happiness is nothing new, of course. Jordan points to a quote by Montesquieu: "If we only wanted to be happy it would be easy; but we want to be happier than other people, which is almost always difficult, since we think them happier than they are." But social networking may be making this tendency worse. Jordan's research doesn't look at Facebook explicitly, but if his conclusions are correct, it follows that the site would have a special power to make us sadder and lonelier. By showcasing the most witty, joyful, bullet-pointed versions of people's lives, and inviting constant comparisons in which we tend to see ourselves as the losers, Facebook appears to exploit an Achilles' heel of human nature. And women—an especially unhappy bunch of late—may be especially vulnerable to keeping up with what they imagine is the happiness of the Joneses.Which makes sense, assuming that one buys the assumption that social software strongly discourages expressions of negativity or unhappiness. This is clearly not the case on all social sites; witness, for example, the (somewhat old) stereotype of the LiveJournal Angstpuppy, characterised by demonstrative levels of self-pity, often encoded into musical and/or sartorial preferences. Granted, that was in an earlier, weirder internet, and might get one unfriended or laughed at in today's more mainstream networks, though one does see a fair amount of kvetching on Facebook. Perhaps the best solution for the collective mental health is to encourage a culture of moderate self-pity and commiseration?

2011/1/21

Mark Dery critically examines at the relentlessly upbeat politics of enthusiasm in the age of the Tumblr blog and the Like button:

At its brainiest, this sensibility expresses itself in the group blog Boing Boing, a self-described “directory of wonderful things.” Tellingly, the trope “just look at this!,” a transport of rapture at the wonderfulness of whatever it is, has become a refrain on the site, as in: ”Just look at this awesome underwear made from banana fibers. Just look at it.” Or: “Just look at this awesome steampunk bananagun. Just look at it.” Or: “Just look at this bad-ass volcano.” Or: “Just look at this illustration of an ancient carnivorous whale.” Because that’s what the curators of wunderkammern do—draw back the curtain, like Charles Willson Peale in “The Artist in His Museum,” exposing a world of “wonderful things,” natural (bad-ass volcanoes, carnivorous whales) and unnatural (steampunk bananaguns, banana-fiber underwear), calculated to make us marvel.Of course, there is a downside to this relentless boosterism: the positive becomes the norm (how many things can you "favourite"?); meanwhile, critical thought becomes delegitimised. When everybody's building shrines to their likes, any expression of negativity is an attack on someone's personal taste, making one a "hater" (a term originally from hip-hop culture which, tellingly, gained mainstream currency in the past decade). From this relentlessly upbeat point of view, critics are no more legitimate than griefers, the players in multi-player games who destroy others' achievements motivated by sadism:

At their wound-licking, hater-hatin’ worst, the politics of enthusiasm bespeak the intellectual flaccidity of a victim culture that sees even reasoned critiques as a mean-spirited assault on the believer, rather than an intellectual challenge to his beliefs. Journal writer Christopher John Farley is worth quoting again: dodging the argument by smearing the critic, the term “hater” tars “all criticism—no matter the merits—as the product of hateful minds.” No matter the merits.The culture of enthusiasm, and the culture of disenthusiasm (which Dery mentions), seems to be founded on the assumption that we are defined by the things we like and dislike. It's a form of commodity fetishism taken into the cultural sphere, though one step removed from the accumulation of material goods, rather dealing with approval and disapproval. Not surprisingly, it's often associated with youth subcultures; take, for example, punks' leather jackets; the names which appear on the back, and those omitted for obviousness or inauthenticity, signal their wearers' authenticity and legitimacy in the culture. (Hipsters take it further, into the realm of irony, where one's status is measured by how close one can surf to the void of kitsch; being into, say, Hall & Oates or M.C. Hammer, is worth more than safe choices like Joy Division and the Velvet Underground, which are so obvious a part of every civilised person's background that trumpeting one's enthusiasm for them is immediately suspect.)

However, likes and dislikes, when worn as badges of identity, can become mere totemism. Do you like, say, The Strokes or Barack Obama, because you find them interesting, or because you wish to be identified as the kind of person who does? Or, as A Softer World put it:

Cultural products (a term which encompasses everything from pop stars to public intellectuals, from comic books to politicians) can fulil two functions: they can be valued for their content or function (does this band rock? Is this book interesting?), or for their function as establishing the consumer's identity. Much like vinyl record sleeves framed on trendy apartment walls by people who don't own turntables to project an aura of cool, favourite books or movies or bands or public figures can be trotted out to buttress one's public image, without ever being fully digested. (Witness, for example, the outspokenly religious American "Conservatives" who idolise Ayn Rand, a strident atheist who expressed a Nietzschean contempt for religion.) Likes and dislike, in other words, are like flags, saluted or burned often out of habit or social obligation as much as any intrinsic value they may hold.

At the end, Dery points out that, far more interesting and telling than what we like or dislike are the things we both like and dislike, or else find fascinating; things which compel us with a mixture of fascination and repulsion, in whatever quantities, rather than neatly falling into one side or the other of the love/hate binary.

Freed from the confining binary of loving versus loathing, Facebook Like-ing versus hateration, we can imagine an index of obsessions, an inventory of intrigues that more accurately traces the chalk outline of who we truly are.

Imagine a more anarchic politics of enthusiasm, poetically embodied in a simulacrum of the self that preserves our repulsive attractions and attractive repulsions, reducing us not to our Favorites, nor even to our likes and dislikes, but to our obscure obsessions, our recurrent themes, the passing fixations that briefly grip us, then are gone—not our favorite things, but the things that Favorite us, whether we like it, or even know it, or not.

2011/1/18

New research has shown that oxytocin, the neurochemical which promotes feelings of love and trust, also induces racism, or to be more precise, sharper discrimination against those ethnically or culturally different from oneself and one's group:

When asked to resolve a moral dilemma, such as choosing to save five lives from a runaway train by sacrificing one life, oxytocin-sniffing Dutch men more often saved fellow countrymen over Arabs and Germans than those who didn’t get a hormonal whiff.

“Earlier research of oxytocin paints a very rosy view of it. We thought it was odd a neurological system that survived evolution would make people indiscriminately loving toward others,” said social psychologist Carsten De Dreu of the University of Amsterdam, co-author of a Jan. 10 study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. “Under oxytocin we saw an increase of in-group favoritism, which has the downside of discrimination against people who are not part of your group.”The questions this raises are interesting. In modern Western society at least, the idea of love is almost a secular religion; it is seen as an unequivocally positive phenomenon, whose only fault is that it is, alas, not everywhere, not washing over everyone and making everything alright. Anyone who dissents from this opinion must be some kind of pitiably twisted curmudgeon; entire subgenres of Hollywood romantic comedies have been made about such sourpusses seeing the light and gaining a new faith in the redeeming power of love, replete with montage sequences. But if the biological conditions underlying the phenomena of love also measurably amplify less positive tendencies, such as reducing empathy to those outside of one's in-group, could love follow religion into becoming something once seen as universally good that has been subjected to more radical reassessment? Perhaps, in future, we'll see the same rational scepticism that has been applied to the virtue of religious faith applied to the universal beneficience of love?

2010/12/30

A study from University College London, involving brain scans correlated with political surveys, has found that self-proclaimed liberals and conservatives have differently shaped brains:

"The anterior cingulate is a part of the brain that is on the middle surface of the brain at the front and we found that the thickness of the grey matter, where the nerve cells of neurons are, was thicker the more people described themselves as liberal or left wing and thinner the more they described themselves as conservative or right wing," he told the programme.

"The amygdala is a part of the brain which is very old and very ancient and thought to be very primitive and to do with the detection of emotions. The right amygdala was larger in those people who described themselves as conservative.

Following in the footsteps of OKCupid's data-mining blog, some people at Facebook have recently analysed a sample of status updates by word category, extracting correlations between word categories (as well as overall subject matter and positivity/negativity), time of day and probability of updates being liked/commented on. The analysis has shown, among other things:

- there are correlations between word categories and age; older people use more first-person plurals, positive emotions and references to religion and family, while young people tend to talk in the singular first-person (presumably adolescent alienation?), mention sadness and death, swear a lot and talk about sex, music and TV.

- People with more friends talk more about social processes and other people, and have higher total word counts; whereas, while talking about home, family and emotions are correlated with having fewer friends, the most strongly correlated categories are time and the past.

- Positive emotions are one of the most likely categories to be liked, but least likely to attract comments. Negative emotions, however, attract a lot of comments (presumably from the people posting empathetic "Don't Like" messages).

- The one thing less likeable than negative emotions is talk about sleeping.

- People who talk about metaphysical or religious subjects are most likely to be friends. And people who use prepositions a lot tend not to be friends with people who swear a lot or exhibit anger or negative emotions.

2010/12/22

Among the British Medical Journal's Christmas season of light-hearted articles this year: Mozart’s 140 causes of death and 27 mental disorders, an amusing piece about the tendency to posthumously diagnose illustrious historical figures:

Schoental, an expert in microfungi, thought that Mozart died from mycotoxin poisoning. Drake, a neurosurgeon, proposed a diagnosis of subdural haematoma after a skull fracture identified on a cranium that is not Mozart’s. Ehrlich, a rheumatologist, believed he died from Behçet’s syndrome. Langegger, a psychiatrist, contended that he died from a psychosomatic condition. Little, a transplant surgeon, thought he could have saved Mozart by a liver transplant. Brown, a cardiologist, claimed he succumbed to endocarditis. On the basis of a translation error of Jahn’s biography of Mozart, Rappoport, a pathologist, thought Mozart died of cerebral haemorrhage. Ludewig, a pharmacologist, suggested poisoning or self poisoning by drinking wine adulterated with lead compounds. For some, Mozart manifested cachexia or hyperthyroidism, but for others it was obesity or hypothyroidism. Ludendorff, a psychiatrist, and her apostles, claimed in 1936 that Mozart had been murdered by the Jews, the Freemasons, or the Jesuits, and assassination is not excluded by musicologists like Autexier, Carr, and Taboga.

What clearly emerges is that Mozart’s medical historiography is made out of various alternatives, with a general time trend as tenable diagnostic hypotheses are progressively exhausted: the more recent they are the less probable. The most likely diagnoses—such as influenza, typhoid fever, and typhus—were proposed first, and only rare and irrelevant conditions such as Goodpasture’s syndrome, Wegener’s granulomatosis, Still’s disease, or Henoch-Schönlein syndrome were left for those who came later.

Thus, highly selective readings of the sources, blatant misquotations, and perversions of the diagnostic criteria have led to shoddy medical interpretations. Mozart allegedly had thought disorder, delusions, musical dysfluency, and epileptic fits, plus he did not actually compose music but merely displayed musical hallucinations. He was a manic depressive, a pathological gambler, and had an array of psychiatric conditions such as Capgras’ syndrome, attention deficit/hyperactive disorder, paranoid disorder, obsessional disorder, dependent personality disorder, and passive-aggressive disorder. This has resulted in psychiatric narratives that blend an uninterrupted long tradition of defamation—the film Amadeus was one of the last public expressions of this tradition.

This phenomenon is Mozart’s medical nemesis. It covers the hidden intent to pull an exceptional creator down from his pedestal through some obscure need to cut great artists down to size. It is reminiscent of Rameau’s nephew in Diderot’s novel who says about people of exceptional creativity: “I never heard any single one of them praised without it making me secretly furious. I am full of envy. When I hear some degrading feature about their private life, I listen with pleasure. This brings me closer to them. It makes me bear my mediocrity more easily.”

2010/12/6

A clinical psychologist at Liverpool University has put forward a proposal to classify happiness as a psychiatric disorder:

It is proposed that happiness be classified as a psychiatric disorder and be included in future editions of the major diagnostic manuals under the new name: major affective disorder, pleasant type. In a review of the relevant literature it is shown that happiness is statistically abnormal, consists of a discrete cluster of symptoms, is associated with a range of cognitive abnormalities, and probably reflects the abnormal functioning of the central nervous system. One possible objection to this proposal remains--that happiness is not negatively valued. However, this objection is dismissed as scientifically irrelevant.

2010/12/5

Satoshi Kanazawa, evolutionary psychology researcher at the London School of Economics, has published a list of ten controversial assertions about human nature; they vary from well-trodden ones (men being naturally sexually promiscuous/drawn to younger partners and such; there are several points drawn from the asymmetry of sexual selection) to more contentious ones; Kanazawa contends that most suicide bombers are Muslims because polygyny, and the sexual frustration of a society where powerful men monopolise the pool of women, serves as powerful motivation, which sounds a bit reductionistic, and would suggest that suicide bombers would predominantly be of low status or prospects, which has not been the case. Meanwhile, liberals are more intelligent than conservatives (as measured by IQ scores) because conservatism is a no-brainer:

"The ability to think and reason endowed our ancestors with advantages in solving evolutionarily novel problems for which they did not have innate solutions. As a result, more intelligent people are more likely to recognise and understand such novel entities and situations than less intelligent people, and some of these entities and situations are preferences, values, and lifestyles," Dr Kanazawa said.

Humans are evolutionarily designed to be conservative, caring mostly about their family and friends. Being liberal and caring about an indefinite number of genetically unrelated strangers is evolutionarily novel. So more intelligent children may be more likely to grow up to be liberals.Also, both creativity and criminality have a common basis in costly peacock-tail behaviour:

The tendency to commit crimes peaks in adolescence and then rapidly declines. But this curve is not limited to crime – it is also evident in every quantifiable human behaviour that is seen by potential mates and costly (not affordable by all sexual competitors). In the competition for mates men may act violently or they may express their competitiveness through their creative activities.

2010/11/19

Today's big question: does country music increase suicide rates? The authors of this paper think that it does, and that country music fans are at significantly higher risk of suicide than nonfans, for reasons involving gun ownership, marital discord and the inherent job and financial stresses affecting America's working poor (which are often referred to in country song lyrics). The authors of this paper, however, dispute this, claiming methodological errors and that there is no evidence of country music making people more likely to off themselves than any other genre. (Whether music in general, or music with lyrics more specifically, correlates to depression or suicide risk, of course, is another question.)

2010/11/4

In his latest Independent column, the inimitable Rhodri Marsden writes about the psychologically brutalising arena of online dating:

Internet dating pivots around profiles; lists of attributes, paragraphs where you attempt to make yourself sound appealing, a handful of flattering photographs. But there's already a problem. Dozens of books and websites offer advice on how to write profiles; third-party services even charge 40 quid to save you the bother. As a result, the uniformity is hilarious. Everyone loves travelling, particularly to Machu Picchu – which, if the profiles are to be believed, is an Inca site swarming with thousands of backpacking singletons. Men are singularly obsessed with skiing. All of us love to curl up on the sofa with a bottle of wine and a DVD (or a VD, as one unfortunately misspelled profile said).