The Null Device

Posts matching tags 'psychogeography'

2017/3/9

I have just spent a little over two weeks in Melbourne; I arrived on occasion of a conference on iOS development, but stayed longer to give me time to catch up with friends. It was my first visit to my old hometown in almost five years.

Melbourne is, I am relieved to say, still here. Just about. Some things are new, some things are gone, and some things remain constant.

Gentrification keeps pushing the virtual Yarra that divides bourgeois and grungy Melbourne northward; it'd now be somewhere around Merri Creek and Brunswick Road.

Fitzroy feels a bit more like South Yarra, a bit brasher and less bohemian. Hip-hop, laptop R&B and house music have largely displaced skronky/jangly indie-rock as its soundtrack. Brunswick Street is now is also a destination for stag/hen-party buses.

Some parts of it are gone (PolyEster Books has closed down, its shopfront a sad shell with a LEASED sign on it and the old roof sign awaiting its inevitable demolition, and the T-shirt shop Tomorrow Never Knows appears to have closed as well), while others remain (PolyEster Records, happily, is still going strong, though they've gotten rid of the neon Dobbshead that was on the wall, as is Dixon Recycled, and Bar Open is still hosting interesting gigs). Smith Street, once colloquially known as “Smack Street”, is reshaping itself as a playground for young people with disposable income, featuring, among other things, several video-game bars (including the arcade-machine bar Pixel Alley) and a burger joint housed inside the shell of an old Hitachi train on the roof of a building (the experience of being inside such a train and it being air-conditioned will be incongruous to those old enough to remember riding in them), not to mention some very nice-looking new flats nearby. There is a new generation of hipster/bro hybrids making Fitzroy their stomping ground. North Fitzroy is largely bourgeois and sterile; bands still play at the Pinnacle, but the Empress, once the crucible of the Fair Go 4 Live Music movement, is under new management and has replaced its bandroom with a beer garden; East Brunswick and Thornbury seem to be becoming more interesting, and Northcote is steadily gentrifying. There are blocks of luxury flats going up everywhere, though most of them have no more than three stories, either because of zoning requirements or perhaps to avoid scaring away buyers from Asia.

Some parts of it are gone (PolyEster Books has closed down, its shopfront a sad shell with a LEASED sign on it and the old roof sign awaiting its inevitable demolition, and the T-shirt shop Tomorrow Never Knows appears to have closed as well), while others remain (PolyEster Records, happily, is still going strong, though they've gotten rid of the neon Dobbshead that was on the wall, as is Dixon Recycled, and Bar Open is still hosting interesting gigs). Smith Street, once colloquially known as “Smack Street”, is reshaping itself as a playground for young people with disposable income, featuring, among other things, several video-game bars (including the arcade-machine bar Pixel Alley) and a burger joint housed inside the shell of an old Hitachi train on the roof of a building (the experience of being inside such a train and it being air-conditioned will be incongruous to those old enough to remember riding in them), not to mention some very nice-looking new flats nearby. There is a new generation of hipster/bro hybrids making Fitzroy their stomping ground. North Fitzroy is largely bourgeois and sterile; bands still play at the Pinnacle, but the Empress, once the crucible of the Fair Go 4 Live Music movement, is under new management and has replaced its bandroom with a beer garden; East Brunswick and Thornbury seem to be becoming more interesting, and Northcote is steadily gentrifying. There are blocks of luxury flats going up everywhere, though most of them have no more than three stories, either because of zoning requirements or perhaps to avoid scaring away buyers from Asia.

Melbourne feels increasingly connected to Asia. In particular, the CBD has become a destination for a combination of property buyers and students from Asia, from bubble-tea bars and a surfeit of Chinese and south-east Asian eateries aiming outside the westernised market to real-estate dealerships aiming at the Chinese market. While there are fewer Japanese migrants and students, the cultural and commercial influence of Japan has been increasing. Japanese food is everywhere; there are increasingly many establishments festooned with red lanterns and purporting to be izakayas, some of which are more authentic than others (Wabi Sabi on Smith St. was excellent), ramen restaurants are popping up, as are Japanese ice cream shops; and then, of course, is the several-decades-old Melburnian institution of takeaway sushi rolls, served in a paper bag with a piscule of soy sauce, as unpretentious fast food. Japanese retail is also making inroads; Uniqlo and Muji have opened shops in Melbourne and the T-shirt label Graniph have a small shop in the CBD. But perhaps most impressive is the Japanese take on the $2 shop, Daiso, a veritable Aladdin's cave of the useful and nifty, each item costing a flat $2.80. (European readers: imagine the Danish chain Tiger/TGR, only distinctly Japanese, with the scale and systemacity that implies.)

Some things remain the same. The trams keep trundling along, with minor route adjustments. The radio station 3RRR, now 40 years old, is going strong as an institution of the alternative Melbourne; an exhibition on its history just finished at the State Library of Victoria, and its stickers are ubiquitous, particularly in the inner north. The live music scene continues apace, in venues such as the Old Bar, Bar Open and the Northcote Social Club. (I saw three gigs in the latter: Lowtide, Pikelet and my favourite band from when I lived in Melbourne, Ninetynine, who are still going strong.) Street art remains an institution in Melbourne, a city where aerosol-art-festooned laneways swarm with tourists and wedding photo shoots and businesses hire “writers“ to decorate their walls with thematic pieces. And the arrival of H&M, in one oddly laid out shop occupying the former General Post Office, doesn't seem to have put Dangerfield out of business.

There are also signs of progress.

Reconciliation with Australia's indigenous population seems to be making tentative symbolic advances, with signs acknowledging the Wurundjeri as traditional owners, and the Wurundjeri word for welcome (“wominjeka”) appearing on signage. Solar panels are on roofs everywhere.

Reconciliation with Australia's indigenous population seems to be making tentative symbolic advances, with signs acknowledging the Wurundjeri as traditional owners, and the Wurundjeri word for welcome (“wominjeka”) appearing on signage. Solar panels are on roofs everywhere.

Cycling as transport seems to be increasingly popular, despite Victoria's mandatory helmet laws (which may have helped scuttle the city's Paris-style bike-rental scheme). And work is beginning on the state's first big public-transport project since the City Loop, the Metro Tunnel, a new underground rail route bringing Melbourne into the club of cities with a subway; currently, one side street near RMIT is largely boarded off to build a shaft for the tunnel boring machines, and both RMIT and Melbourne University are bracing for the hit to student numbers that three years of nearby disruptive works will pose.

Cycling as transport seems to be increasingly popular, despite Victoria's mandatory helmet laws (which may have helped scuttle the city's Paris-style bike-rental scheme). And work is beginning on the state's first big public-transport project since the City Loop, the Metro Tunnel, a new underground rail route bringing Melbourne into the club of cities with a subway; currently, one side street near RMIT is largely boarded off to build a shaft for the tunnel boring machines, and both RMIT and Melbourne University are bracing for the hit to student numbers that three years of nearby disruptive works will pose.

2012/9/17

William Gibson talks about how the internet changed the idea of “bohemia” by eliminating the scarcity and locality of subcultures and scenes, instead replacing it with everything, everywhere, all the time:

(If punk emerged today:) You’d pull it up on YouTube, as soon as it was played. It would go up on YouTube among the kazillion other things that went up on YouTube that day. And then how would you find it? How would it become a thing, as we used to say? I think that’s one of the ways in which things are really different today. How can you distinguish your communal new thing — how can that happen? Bohemia used to be self-imposed backwaters of a sort. They were other countries within the landscape of Western industrial civilization. They were countries that most people would never see — mysterious places. You’d pay a price, potentially, for going there. That’s always cool and exciting. Now, where are they? Where can you do that? How are people transacting that today? I am pretty sure that they are, but I don’t have that much firsthand experience of it. But they have to do it in a different way.Meanwhile, Justin Moyer of the band El Guapo writes about the Brooklynisation of indie music, and how a vaguely Williamsburg-flavoured global hipsterism has displaced the myriad different, wildly divergent local scenes that used to exist, literally or metaphorically “over the mountains”:

Regional music scenes differentiate Hill Country blues from Delta blues and New York hardcore from Orange County hardcore from harDCore. RMSes draw lines between KRS-One and MC Shan, Louis Armstrong and Charlie Parker, Merseybeat and The Kinks, Satie and Wagner. RMSes are why I would almost never play a show that wasn’t all ages in D.C., but would only play Joe’s Bar in Marfa, Texas. RMSes make you think differently.

Like accents, RMSes are disappearing. Sure, record stores and record labels are dead or living on borrowed time. Sure, smart clubowners can’t afford to book a show for an unknown, out-of-town band instead of an ’80s dance party. But money’s not the problem—or, at least, not the only problem. RMSes are disappearing because everyone is starting to sound like everyone else.The opposite of the regional music scenes is the globalised Brooklyn, based loosely though not entirely on the real Brooklyn, a place where the sheer concentration of hip, creative young people and potential collaborators absorbs talent from other areas, absorbing it into a melting-pot monoculture where everything is linked to everything else and there are no secrets:

Do not confuse Brooklyn with, well, Brooklyn—the New York borough that sits about 230 miles from Washington on the southwest end of Long Island over the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge off of I-278. There are many Brooklyns. Los Angeles is Brooklyn. Chicago is Brooklyn. Berlin and London are Brooklyn. Babylon was the Brooklyn of the ancient world. In the 1990s, Seattle was Brooklyn. Young Chinese punks challenging Communism risk prison to make Beijing the Brooklyn of tomorrow. Some Brooklyns aren’t even places. MySpace is Brooklyn. YouTube is Brooklyn. Facebook is Brooklyn. Spotify and iTunes are perversely, horribly, unapologetically, maddeningly Brooklyn.

What this essay is saying: In Brooklyn, there is too much input.

What this essay is saying: If music wasn’t better before Brooklyn, it was, at least, weirder.

What this essay is saying: In Brooklyn, music comes too cheap. (Please note: “too cheap” doesn’t refer to price.)

What this essay is saying: A melting pot is not an aesthetic. Neither is a salad bar.

What this essay is saying: There is a tidal wave of generic, mushy, apolitical, featureless, Brooklynish music infiltrating the world’s stereos.

What this essay is saying: Beware what you put on your iPod. It might not be dangerous.

2011/2/14

The Quietus has an interview with The Human League, (who have a new album coming out, apparently skipping the whole 80s synthpop nostalgia circuit and focussing on making dancefloor-oriented electronic music). Anyway, the interview includes an interesting assertion that boring places (like Sheffield, allegedly) produce more interesting music than exciting places (like London):

(Joanne:) But Sheffield isn’t just about that; obviously you’ve got the Arctic Monkeys as well. It’s a very, very arty town. It’s a bit dull...

(Susan:) I think it is because it’s a bit boring. There isn’t much going on. You only have to go across the Pennines to Manchester and suddenly you're in a different world; it’s very cosmopolitan. You come back to Sheffield and it’s a bit... boring! And I don’t think that’s necessarily a bad thing because it creates creativity.

But that’s why good bands don’t come from London. Ambitious bands move to London to become famous but that’s not the same thing... even during punk and post-punk when you had a lot of people coming through, a lot of these bands were more associated with places like Bromley, which are satellite towns or else they came from squatted communities where people couldn’t afford any of the entertainment options that London offered.

2010/12/16

Data visualisation of the day: if you draw lines between the locations of people connected to each other on Facebook, you get this map of connections:

A few interesting observations:

- There are notable dark patches: China is an obvious one, between the Great Firewall and the prevalence of home-grown websites. Brazil is also dark (presumably because everyone's on Orkut instead), as is Russia (LiveJournal is apparently the big thing there to this day). The Middle East is also largely Facebookless, with the exception of Turkey, Lebanon and Israel. Africa is also largely dark, with a few, largely self-contained patches of light.

- The east coast of Australia is more strongly connected to New Zealand than to the west coast.

2010/11/28

More on the impending closure of the Luminaire, arguably London's best music venue today, in the Guardian:

Widely regarded as the best small independent music venue in London, the Luminaire had it all: a booking policy of rare love and eccentricity, a beautiful performing space resplendent with mirrorball, and knowledgeable staff. Uniquely, it also had signs on the walls reminding punters that "no one paid to listen to you talking to your pals. If you want to talk to your pals when the bands are on, please leave the venue." This – along with outbreaks of shushing if anyone had the cheek to disobey the sign – allowed quieter, more delicate bands to thrive in a way simply not possible at other, more sticky-floored spaces.

The closure seemed to be part of a disturbing trend. In recent months London has also lost The Flowerpot, Barden's Boudoir, and The Cross Kings, with the 100 Club also struggling for survival. Sometimes all one wants is to go to a gig that isn't sponsored by a brand of lager or a mobile phone company. With the corporate takeover of indie music, small and proudly independent venues such as these felt increasingly like little beacons of charm in a sea of monochrome.Various possible reasons for the closure are being advanced, from increases in onerous licensing requirements (now where have I heard that before?) to it, unfortunately, being too far north-west, implying that London's live music map is becoming homogeneously centralised around the stereotypically hipsterish areas of Shoreditch and Dalston, with all outside that area being fit only for naff cover bands. I wonder whether this could be a symptom of a deeper polarisation of London, with creative expression being confined to an inverse ghetto of sorts in the East End, and the rest of London becoming less receptive to such things.

2010/6/29

An interesting piece by Financial Times writer Simon Kuper on the cultural impact of Eurostar; how the cross-channel train service between London and Paris (Brussels doesn't rate a mention) has transformed the cultures of both cities; before, things used to be much different:

Until the 1990s, To Britons Paris seemed almost as exotic as Jakarta, and more so than Sydney or San Francisco. There was that famous smell of the French Métro, the mix of perfume and Gauloises cigarettes. There was the bizarre sight of people drinking wine on pavements. There was all that philosophy. The exoticism of Paris became such a staple of English-language writing that comedians began to parody it. “I come upon a man at an outdoor café,” writes Woody Allen. “It is André Malraux. Oddly, he thinks that I am André Malraux.”

Those first trains connected two fairly insular cities. I had returned to Britain from Boston the summer before the Eurostar was launched, and after the Technicolor US, I was shocked by dingy London. Tired people in grey clothes waited eternities on packed platforms for 1950s Tube trains. Coffee was an exotic drink that barely existed, like ambrosia. Having a meal outside was illegal. The city centre was uninhabited, and closed at 11pm anyway. Air travel was heavily regulated, and so flying to Paris was expensive. Going by ferry took a whole miserable day. If you did get across, and only spoke the bad French most of us learnt at school, it was hard to communicate with any natives.Now, London and Paris have converged somewhat; London has shaken off some of its Anglo-Saxon austerity and embraced a more Continental lifestyle, with outdoor bdining, late-closing bars and gourmet food markets, and even got a taste for French-style grands projets, not least of all St. Pancras International, the Eurostar terminus. (As for coffee, I can only imagine that, before 1994 or so, anyone requesting coffee rather than tea would be met with a mug of Nescafé Blend 43 or similar.) Meanwhile, Paris has shed some of its Gallic hauteur and become more London-like:

But with the inventions of the internet and Eurostar, and globalisation in general, many Parisians began to see that there was a wonderful new life to be seized if you spoke English. Paris could choose to become an inhabited museum, a sort of chilly Rome, but if it wanted to remain in touch with the latest ideas, the Parisian establishment would have to learn English. By and large, the younger members did. The canard that Parisians refuse to speak English is a decade out of date. As I write, every car on the street outside my office is festooned with a flyer for English lessons for children. Parisian parents are now so keen to induct their toddlers into the global language that speaking English has become a weapon for us Anglophone parents in the battle for a spot in a crèche.Of course, some differences remain (French children are apparently quieter and cleaner than the mowfy brats of Britain, while Britons dress more colourfully, in "weird youth-culture outfits"), but they're becoming less distinct, as more people commute or travel between the two cities. (London is apparently now, by population, the sixth-largest French city.)

Kuper goes on to describe a bright future for western Europe, largely due to its compact geography, further amplified by the promise of high-speed rail. Indeed, shiny, aerodynamic high-speed trains seem to be the unchallenged future of travel, with air travel, that darling of the 1990s, looking a bit shabby, between rising oil prices, the Long Siege and things like the Icelandic volcanic ash cloud.

2010/6/13

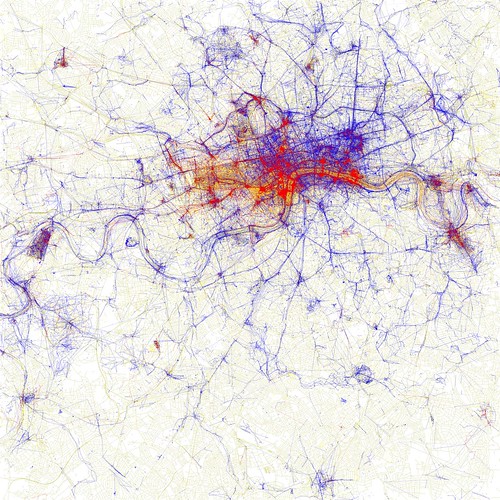

Data visualisation of the day: Locals and Tourists. Location data was harvested from geotagged photos on Flickr and plotted on maps; the points were colour-coded: blue if the poster was a local (i.e., had been in the city for more than a period of time), red if they were tourists (recent visitors with no prior history), and yellow if it was ambiguous. Here, for example, is London, with the Thames and the West End ablaze with red and the East End blue (which means that there are fewer tourists but still plenty of photographers, think Hackney art hipsters and/or kids with iPhones):

And here are Paris; tourists flock to the obvious parts (the Eiffel Tower, the Champs-Elysees, the Seine and the Île-de-Cité), whereas the locals who tend to post photos gravitate to the east, around the Bastille and such; the affluent, conservative southern arrondisements are largely a wasteland, photographically at least. In Berlin, meanwhile, tourists fill the city's broad central boulevards, the Tiergarten and Alexanderplatz and Karl-Marx-Allee, and visit the East Side Gallery, but there's a lot of local photography happening around Kreuzberg/Neukolln.

In fact, one could use the frequency of non-tourist photography for an area as a predictor of cultural vibrancy. Areas where a lot of photos are taken by people who live in the same city and not by tourists could be the kinds of broad areas where local scenes form, and the kinds of people who engage in cultural activity beyond passive consumption (sometimes referred to as "hipsters") are more likely to be found. This is borne out by other maps: Melbourne (there are specks of blue around the inner north, while the sprawling suburbs are largely empty). In New York, meanwhile, Manhattan glows with tourist activity but Brooklyn is veined with blue.

Of course, the amount of blue space on these maps is considerably larger than any nexus of cultural activity would be; it'd cover the areas where events take place, where the participants live and work, and spaces in between. However, it does make one wonder whether one could data-mine the buzz of a city by correlating Flickr photo geodata or other indices of participation with other data; possibly transport routes?

2010/6/12

An article in the Graun asks whether the internet and the rise of music blogs has killed the idea of a local music scene, replacing a world of local scenes from Merseybeat to Madchester to the Seattle Sound with something a lot less connected to geography:

The idea of the local scene has always been an attractive prospect, playing on tribal mentalities and a very human desire for order. It has helped define emerging music, and in so doing, endowed places with certain musical characteristics that come to be seen as inalienable (play musical word association, and see what comes after Seattle). But recently, local scenes seem to be dying out. With the advent of the internet, the way we consume and create music has changed. We still turn to genres to help define sound, but these days these scenes are often built on artists who share nothing in terms of geography – disparate bedroom artists such as Washed Out, Toro Y Moi and Memory Tapes find themselves lumped together under the "chillwave" banner by bloggers and internet communities drawing parallels in sound, though their bedrooms are hundreds of miles apart.There have been non-local scenes before the rise of the blogs; the Messthetics DIY cassette scene of the 1980s, with geeky sorts making casiopunk jams in sheds all over the third-tier provincial towns of Britain and mailing them out on cassettes, was one; if you haven't heard of it, that probably says more about the impact the internet has made than anything else. Before the internet, finding like-minded individuals outside of one's own area was prohibitively difficult; a few isolated individuals may have struggled, mailing zines and cassettes (and, for a while, CD-Rs) to each other, but their numbers dropped every time one of them either managed to move to a culturally active area and became too busy going to gigs and jamming in bands to keep up or just stopped bothering and instead decided to watch TV or build model train sets, or else traded in one's studio and music-making time for the responsibilities of parenthood or one's career.

Now, of course, with music blogs at one end, self-publishing services like SoundCloud and Basecamp at the other and sites like Facebook and last.fm tying it together, participating online is not a sign of loserdom, a poor substitute for the real thing for those too far from the action, but is itself part of the action. (A similar destigmatization happened in the area of online dating over the past decade, and one could argue that a similar phenomenon is at work in online gaming; compare the mainstream social acceptability of FarmVille to that of traditional MMORPGs.) Even the cool kids in Williamsburg or Prenzlauerberg post their MP3s and animations online (not to mention Hipstamatic photos of them being ironically drunk-faced at the latest art party); and when it comes to making art, promising voices from outside aren't automatically shut out.

The other side of the coin is, of course, the ongoing process of gentrification. Music scenes become established in places which are geographically compact and cheap, and as they thrive, they attract hipsters, then non-creative but fashion-following trendies, and then purely materialistic yuppies, until finally the original artists are priced out, and the area soon belonging only to those with the means of buying their way in (look at Brooklyn, for example; according to Patti Smith, this renowned hipster mecca has closed itself off to the young and struggling and, if Gavin McInnes is to be believed, today's Williamsburg hipsterati are pretty much exclusively the scions of America's top stratum, doing a sort of combination grand tour/rumspringa of the artistic/bohemian lifestyle before taking their rightful places as captains of industry; Vampire Weekend are unique only in the extent to which they make this explicit in their lyrics and attire). As focussed inner cities become more attractive and expensive, pricing artists out, and technology obviates the need for proximity, is the future of art looking more atomised? Will creativity move out of the physical world and into networks of alienated bedrooms in impoverished dormitory suburbs or small towns, and the distribution of artists (by which I mean active contributors to artistic discourse, not creatively-attired scenesters and poseurs) spread out more uniformly over the landscape, in the way that, say, open-source programmers (also contributors to the creative economy, though not as likely to parlay that into social status or sexual success) are?

One good thing coming from this, though, is that, with the decline of geographically delimited scenes, bedroom musicians are freed of pressure to conform to local norms; when one's scene is a network of blogs, it's easier to move to a different scene (or be discovered by one). Physical scenes, however, tend to impose their values, and often exclude or actively scorn those who don't conform. Take, for example, the blues-rock monoculture in 1970s Australia, or the vaguely homophobic anti-synthesizer backlash of the early 1980s there; one could, indeed, adapt another Australian term to apply to this phenomenon, and call it the Tyranny of Proximity.

Kev Kharas of the influential blog No Pain in Pop believes that new music is purer as a result. "There is no pressure to conform to any kind of scene etiquette," he says. "It frees up people to get closer to something they want to do, rather than making music that's responding to staid ideas." While the music industry has been panicking over lost record sales from file-sharing and free downloads, a quiet creative revolution has been taking place behind the scenes.Of course, not everybody's happy with this. Some grumpy old men don't like it one bit:

"When we were kids, we'd give our eye's teeth for a bootleg of an early Bo Diddley track," says Billy Childish, who has championed localism in north Kent as part of the Medway scene of garage rock bands and the Medway Poets. "Now, you can have everything you want just when you want it. We've got this massive problem where it's Christmas every day. It's difficult to find the edges."

2010/5/24

In the wake of Brighton electing Westminster's first Green MP, the Grauniad's Alexis Petridis (best known for his music articles) takes a look at the place and its various contradictions:

Brighton is, after all, the perennially irksome, unofficial British capital of what the late rock critic Steven Wells once memorably described as "crusty-wusty, hippy-dippy, twat-hatted, ning-nang-nongers". Of course it elected someone like Lucas – who was recently photographed at home, standing, alas, before a shelf laden with self-help books called things like Awaken the Giant Within.

I walk past The World's Least Convincing Transvestite every day, on the way to my office. A man who has made the bold fashion decision to sport a jaw-dropping combination of earrings, eyeshadow, stubble and shaving rash on a daily basis, he has all the bewitching femininity of a rugby league prop forward in a pencil skirt; by comparison, Grayson Perry is the absolute spit of Audrey Hepburn. Judging by his clothes – demure court shoes, tights, pussy-bow blouse – he's en route to a clerical job in an office. For all I know, he might be facing yet another day of bruising homophobia and derision from his colleagues, but it doesn't look like it. He just looks like an ordinary bloke on his way to an ordinary job, albeit dressed as a woman. I've got a sneaking suspicion his workmates just let him get on with it. And if they do, that would be very Brighton.

There's been a lot of talk about the middle-class gentrification of Brighton over the last decade, but it doesn't seem to have impacted much on the city's famous air of slightly seedy licentiousness, on Keith Waterhouse's famous judgment that it's a town that always looks as if it's helping police with their inquiries. It now looks like a town that's helping police with its inquiries while enjoying an organic, locally sourced panini.As Brightonian crime writer Peter James points out, the city does have a dark side, and it could be that that gives it its edge and keeps it from turning into just another haven for moneyed yuppies to bring up their cosseted kids:

And nowadays, several police officers have told me, it's one of the favourite places for top criminals to live in the UK. You've got two seaports on either side, you've got Shoreham airport with no customs post, you've got masses of unguarded coastline and a quick train to London; in other words - a fast exit. Then you've got the largest number of antique shops in the UK for fencing stuff, and you've got a massive recreational-drug market with two universities, a big gay population and arty middle-class residents. One of Brighton's distinctions – although the local tourist office doesn't talk about it - is that it's the drug-injecting death capital of the UK, and has been for nine years (we lost the title to Liverpool for a year or so, but we've got it back now).

2010/5/1

Some recent random posts related to urbanism, urban planning, architecture, transport, infrastructure and such:

- The World's Strangest Housing Communities. Includes Chinese replicas of American suburbia, sadly derelict futuristic pod cities in Taiwan (alas, now destroyed), and rumours of midget villages in rural America. Not to mention Alphaville, the chain of high-security gated cities in which Brazil's professional élites live behind electrified fences, guarded by a private army and entering and leaving only by helicopter (and which inspired a Jean-Luc Godard film of the same name),

- A Berlin-based street artist calling themself EVOL uses photographic prints to convert utility boxes and planters into miniature replicas of decaying tower blocks:

- A piece on hand-drawn maps, and the situations in which they are particularly useful, when subjective psychogeographic experience is more important than objective accuracy.

- A piece in The Economist about Portland, Oregon, a city which "looks to Amsterdam, Helsinki and Stockholm for ideas" and is touted by some as a model for a more sustainable America (though also mocked for being the cultural epicentre for hipsters and White People.

- Another possible alternative for living: Inhabited balloon cities perched atop high-altitude wind systems.

2010/2/28

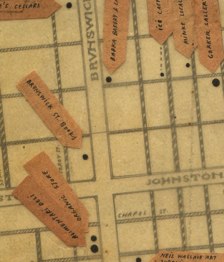

Acclaimed Melbourne street artists/underground illustrators Miso and Ghostpatrol have released

a downloadable, printable map of inner Melbourne (or, as some would argue, the parts of Melbourne White People like). The map consists of two sheets, covering the CBD and Fitzroy, and showing the locations of cafés, bars, art spaces and art supply shops; it may be downloaded from here.

Acclaimed Melbourne street artists/underground illustrators Miso and Ghostpatrol have released

a downloadable, printable map of inner Melbourne (or, as some would argue, the parts of Melbourne White People like). The map consists of two sheets, covering the CBD and Fitzroy, and showing the locations of cafés, bars, art spaces and art supply shops; it may be downloaded from here.

The choice of the CBD and Fitzroy suggests that gentrification doesn't seem to have affected the north/south divide. North of the Yarra is hip and culturally rich, whereas south of the Yarra is merely trendy, a shallow, consumeristic imposter for actual cool; St. Kilda (once the crucible of punk—blah blah blah Nick Cave blah blah Seaview Ballroom— but now, as The Lucksmiths so appositely worded it, home of bright-eyed boys in business suits, tourists where once were prostitutes) and Prahran (which committed the cardinal sin of getting house music and T-shirt boutiques a decade before Fitzroy) don't rate a mention in the psychogeography of cool in Melbourne. And while Fitzroy real estate prices approach South Yarra levels, there is still enough of a cultural legacy (not to mention tram routes from more affordable areas) to maintain the area's claim to cultural vitality.

2010/2/9

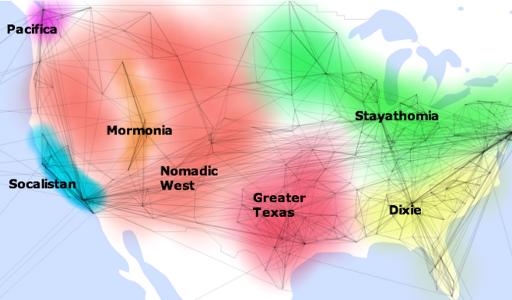

Pete Warden, a programmer and amateur researcher, has analysed the data from public Facebook profiles, including the relative locations of pairs of friends and people's names and fan pages, and used this to divide the US into seven relatively self-contained clusters, which he terms "Stayathomia" (i.e., the northeast to midwest), "Dixie" (the old South), "Greater Texas" (encompassing Oklahoma and Arkansas), "Mormonia" (no prizes for guessing where that is), the "Nomadic West" (places like Idaho, Oregon and Arizona, where people's connections span wide areas), Socalistan (i.e., most of California and parts of Nevada) and Pacifica (essentially Seattle). The clusters were derived from performing cluster analysis on the social graph, and not imposed on the data a priori.

Warden posts various findings he gained from crunching the data on these clusters:

Probably the least surprising of the groupings, the Old South is known for its strong and shared culture, and the pattern of ties I see backs that up. Like Stayathomia, Dixie towns tend to have links mostly to other nearby cities rather than spanning the country. Atlanta is definitely the hub of the network, showing up in the top 5 list of almost every town in the region. Southern Florida is an exception to the cluster, with a lot of connections to the East Coast, presumably sun-seeking refugees. God is almost always in the top spot on the fan pages, and for some reason Ashley shows up as a popular name here, but almost nowhere else in the country.

(Greater Texas:)God shows up, but always comes in below the Dallas Cowboys for Texas proper, and other local sports teams outside the state. I've noticed a few interesting name hotspots, like Alexandria, LA boasting Ahmed and Mohamed as #2 and #3 on their top 10 names, and Laredo with Juan, Jose, Carlos and Luis as its four most popular.

(Mormonia:) It won't be any surprise to see that LDS-related pages like Thomas S. Monson, Gordon B. Hinckley and The Book of Mormon are at the top of the charts. I didn't expect to see Twilight showing up quite so much though, I have no idea what to make of that!Mormons like their vampires sparkly and pro-abstinence; who would have guessed?

(Socalistan:) Keeping up with the stereotypes, God hardly makes an appearance on the fan pages, but sports aren't that popular either. Michael Jackson is a particular favorite, and San Francisco puts Barack Obama in the top spot.Warden also has this tool for browsing aggregate profiles of countries based on their residents' public Facebook profiles.

2010/1/19

From a Momus blog post, in which he, on departing from Osaka, speculates on how he might possibly live there:

I've never seriously thought about living in Osaka before. I love Tokyo best of all. But increasingly, my outlook has Berlinified, by which I mean I regard expensive cities like New York, London and Tokyo as unsuited to subculture. They're essentially uncreative because creative people living there have to put too much of their time and effort into the meaningless hackwork which allows them to meet the city's high rents and prices. So disciplines like graphic design and television thrive, but more interesting types of art are throttled in the cradle.Momus raises an interesting observation, and one which may seem somewhat paradoxical at first. First-tier global cities, like London, New York, Paris and Tokyo are less creative than second-tier cities, largely due to the increased pressure of their dynamic economies making all but the most commercial creative endeavours unsustainable. I have noticed this myself, having lived both in Melbourne (Australia's "Second City" and home of the country's most vibrant art and music scenes; generally seen by almost everyone to be ahead of Sydney in this regard) and London (a city associated, in the public eye, with pop-cultural cool, from the Swingin' Sixties, through punk rock and Britpop, but now more concerned with marketing and repackaging than creating; it also serves as the headquarters of numerous media companies and advertising agencies). In London, it seems that people are too busy working for a living to make art in the way they do in Melbourne or Berlin, and the arts London leads in are the commercial ones Momus names Tokyo as leading in: graphic design, the media, and countless onslaughts of meticulously market-researched "indie" bands. Those who thrive in London (and presumably New York, Paris and Tokyo) tend to be not the free-wheeling bricoleurs but the repackagers and cool-hunters, one eye on the stock market of trends and another on the repository of past culture, looking for just the right thing to pick up and just the right way to market it. (Examples: various revivals (Mod, Punk, New Wave), each more cartoonish and superficial than the last.) "Moving to London" is an artistic cliché, shorthand for wanting to hit the commercial mainstream, to surf the big waves.

There are, of course, counter-examples, but they tend to be scattered. For one, the more vibrant a cultural marketplace a city is, the more money is floating around, the more rents and prices are driven up, and the more those who are not driven by a commercial killer instinct find themselves unable to keep up, without either channeling their energies into money-spinning hackwork or whoring themselves to the marketing ecosystem, subordinating their creative decisions to its meretricious logic.

Also, as Paul Graham pointed out, cities have their own emphases encoded in their cultures; a city is made up as much of cultural assumptions as buildings and roads, and there is only space for one main emphasis in a city. If it's about commerce or status, it's not going to be about creative bricolage. (This was earlier discussed in this blog, here.) The message of a city is subtle but pervasive, replicating through the attitudes and activities of its inhabitants, subtly encouraging or discouraging particular decisions (not through any system of coercion, but simply through the interest or disinterest of its inhabitants). As Graham writes, Renaissance Florence was full of artists, wherea Milan wasn't, despite both being of around the same size; Florence, it seems, had an established culture encouraging the arts and attracting artists, whereas Milan didn't.

When a city is said to be first-tier—in the same club of world cities as London and New York—the implication is that its focus is on status and success, and the city attracts those drawn to these values, starting the feedback loop. Second-tier cities (like Melbourne and Berlin and, according to Momus, Osaka) are largely shielded from this by their place in the shadows of first-tier cities and their relatively cooler economic temperature. (There's a reason why music scenes flourish disproportionately in places like Manchester and Portland, often eclipsing the Londons and New Yorks for a time.) Of course, as second-tier cities are recognised as "cool", they begin to heat up and aspire towards first-tier status. (One example is San Francisco; formerly the hub of the 1960s counterculture (which, of course, birthed the personal computing revolution), then the seat of the dot-com boom, and now promoting itself as the Manhattan of the West Coast.) Cities, however, fill niches; they can't all be New York, and the number of first-tier "world cities" is, by its nature, limited.

2008/10/22

Author and psychogeographer Iain Sinclair (best known for his somewhat hermetic writings about walks around greater London) has apparently been banned by Hackney Council from launching a book at Stoke Newington Library, seemingly because of critical remarks he made about the 2012 Olympics:

Then, last Friday night, I had a call to say sorry, but the invitation was withdrawn. It seemed a diktat had come down from above that I was a non-person and should be barred from the library for the crime of writing an off-message piece on the Olympics. This essay, published in the London Review of Books, responded to aspects of the creation of the Olympic Park in the Lower Lea Valley: the destruction of the Manor Garden allotments, the eviction of travellers, and the famous "legacy" revealed as nothing more than a gigantic shopping mall in Stratford.

The essay had very little to do with the book I was invited to launch. Challenged, the council shifted its ground: I was controversial. Controversy was not allowed in libraries. There could, presumably, be no discussion of stem-cell research or Afghanistan. And Hackney, That Rose-Red Empire fell into that category. A conclusion Hackney was miraculously able to reach without reading a line of a book that won't be published for another three months.

While researching my memoir, I walked back to the Stoke Newington Library and asked for the local history section. They told me that there wasn't one. History had been declared redundant. All that was left were half a dozen pamphlets in a box kept under the desk.More proof that the Olympics is, by its essential nature, a totalitarian project incompatible with free speech?

2008/8/29

Britain's most senior cartographer has railed against electronic maps, arguing that they obliterate the rich geography of Britain, reducing an ancient landscape filled with history to a set of roads:

Churches, cathedrals, stately homes, battlefields, ancient woodlands, rivers, eccentric landmarks and many more features which make up the tapestry of the British landscape are not being represented in online maps, which focus on merely providing driving directions, said Mary Spence, President of the British Cartographical Society.

"Corporate cartographers are demolishing thousands of years of history, not to mention Britain's geography, at a stroke, by not including them on maps," she said. "We're in danger of losing what makes maps unique; giving us a feel for a place."While Spence's complaint seems superficially plausible, it misses the forest for the trees (no pun intended), focussing on the specifics of the implementations of a yet novel technology and ignoring the momentum that is driving progress forward. It's true that, when you look at a map in Google Maps or on a satnav unit, it, by default, shows you a minimalistic, functional map, consisting of sparse lines rendered in brightly coloured pixels. However, it is also true that there is more than that beneath the surface. Google Earth, Google Maps' big brother, renders the globe with a panoply of user-selectable layers, from the standard geographical landmarks (roads, railways, cities) to links to geotagged Wikipedia pages and photographs (albeit on some weird service nobody uses because everyone's on rival Yahoo!'s Flickr). Google Earth itself allows users to draw their own layers and send links to them. And OpenStreetMap takes it one step further, doing for mapping what Wikipedia did for textual reference works; if you find that your map of Gloucestershire is missing Tewkesbury Abbey or your map of Cental Asia got the Aral Sea wrong, you can correct it. And if you live somewhere where there is no Google Maps (and, indeed, no Ordnance Survey), you can map it yourself (or get some friends together to map it; or petition the local government/chamber of commerce to buy a few GPS units and pay some people to drive around with them, assembling a map). This has resulted in excellent maps of places Google hasn't reached yet, like, say, Reykjavík, Buenos Aires and much of Africa.

Making maps is only half of the equation; it's when one considers what can be done with all the mapping data that things become really exciting. Now that mobile data terminals (which people often still refer to as "phones"), with wireless internet connections and GPS receivers, are becoming commonplace, these soulless, history-levelling map databases are transformed into a living dialogue with and about one's surroundings. Already mobile phones which can help you find various amenities and businesses near where you are are being advertised. It is trivial to imagine this extended from merely telling you where the nearest public toilet is or how to get home from where you are into less mundane matters. Press one button, it points out historical facts about your location, with links to Wikipedia pages; press another one, and it scours online listings and tells you what's happening nearby. Follow any link to flesh out the picture as deeply as you have time for.

Spence's argument reminds me of a lot of the beliefs about computers from the 1950s, when computers were expensive, hulking beasts which were programmed laboriously using punched cards and rudimentary languages like FORTRAN and COBOL. It was too easy to extrapolate the status quo, the baby steps of a new technology, in a straight line and see a future of centralised hegemony and soul-crushing tedium, where the world is reorganised around the needs of these primitive, inflexible machines. Of course, that world never came about, as the machines evolved rapidly; instead of being marshalled into centrally computerised routines, we got iPods, blogs and Nintendo Wiis. To suggest that computerised maps will reduce our shared psychogeography to a collection of colour-coded roads is similarly absurd.

2008/5/29

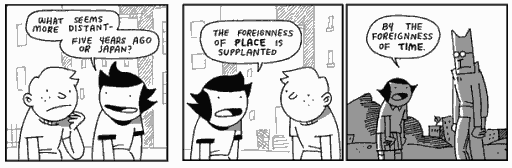

The writer L.P. Hartley once stated that the past is a foreign country where they do things differently. Today's Cat And Girl revises this, arguing that, in the age of globalisation, instantaneous communication and accelerating change, our past is more foreign to our present selves than actual foreign countries are.

2008/5/28

Paul "Hackers and Painters" Graham has an interesting essay on the implicit messages that cities send to their inhabitants:

Great cities attract ambitious people. You can sense it when you walk around one. In a hundred subtle ways, the city sends you a message: you could do more; you should try harder.

The surprising thing is how different these messages can be. New York tells you, above all: you should make more money. There are other messages too, of course. You should be hipper. You should be better looking. But the clearest message is that you should be richer.

What I like about Boston (or rather Cambridge) is that the message there is: you should be smarter. You really should get around to reading all those books you've been meaning to.

How much does it matter what message a city sends? Empirically, the answer seems to be: a lot. You might think that if you had enough strength of mind to do great things, you'd be able to transcend your environment. Where you live should make at most a couple percent difference. But if you look at the historical evidence, it seems to matter more than that. Most people who did great things were clumped together in a few places where that sort of thing was done at the time.Graham lists the messages sent by other cities: while New York is about money and Cambridge, Massachusetts, is about knowledge, Silicon Valley is all about power, Berkeley is about being civilised and living better, while Washington DC and Los Angeles are about whom you know, although in different ways. Internationally, Oxford and Cambridge (the original one) are intellectual, though not as strongly as Cambridge, MA. Paris is about style (people care about art there, though it's not an intellectual centre). Meanwhile, London is residually about being more aristocratic (at least, when viewed from an American viewpoint), though also places a value on "hipness", and keeping abreast of trends.

He also speculates that this effect, by which a city accumulates a set of values and, in its outlook, encourages certain motivations (whilst implicitly discouraging ones at odds with them), was behind historical phenomena such as mediæval Florence being home to a disproportionate number of artists compared to other, equally big, cities.

You can see how powerful cities are from something I wrote about earlier: the case of the Milanese Leonardo. Practically every fifteenth century Italian painter you've heard of was from Florence, even though Milan was just as big. People in Florence weren't genetically different, so you have to assume there was someone born in Milan with as much natural ability as Leonardo. What happened to him?

If even someone with the same natural ability as Leonardo couldn't beat the force of environment, do you suppose you can?The power of the invisible cultural environment, as manifested in a myriad tiny things, to nurture or thwart ambitions is powerful:

No matter how determined you are, it's hard not to be influenced by the people around you. It's not so much that you do whatever a city expects of you, but that you get discouraged when no one around you cares about the same things you do

There's an imbalance between encouragement and discouragement like that between gaining and losing money. Most people overvalue negative amounts of money: they'll work much harder to avoid losing a dollar than to gain one. Similarly, though there are plenty of people strong enough to resist doing something just because that's what one is supposed to do where they happen to be, there are few strong enough to keep working on something no one around them cares about.

Because ambitions are to some extent incompatible and admiration is a zero-sum game, each city tends to focus on one type of ambition. The reason Cambridge is the intellectual capital is not just that there's a concentration of smart people there, but that there's nothing else people there care about more. Professors in New York and the Bay area are second class citizens—till they start hedge funds or startups respectively.

At the moment, San Francisco's message seems to be the same as Berkeley's: you should live better. But this will change if enough startups choose SF over the Valley. During the Bubble that was a predictor of failure—a self-indulgent choice, like buying expensive office furniture. Even now I'm suspicious when startups choose SF. But if enough good ones do, it stops being a self-indulgent choice, because the center of gravity of Silicon Valley will shift there.Speaking as one who has moved from Melbourne to London, this rings true. Melbourne seems more about creativity and collaborative expression, whereas London is more about status and success. In Melbourne, people get involved in creative projects that don't have a career or strategy for success attached to them, be it making zines, playing music or other arts. In London, it's more about success; all the artists want to be Damien Hirst or Tracey Emin (or, indeed, Banksy) and all the indie bands have stylists and want to be on the cover of NME. (All of this reflects itself in the nature of art produced here; the calculatedly stylised nature of it, falling in a spectrum between naked commercialism and (equally mercantile) fashion-driven hipness.) People pay more attention to keeping score here, and that affects the way the game is played. If you tinker around on creative projects with no commercial potential, you may as well be building model train sets in your shed, or, indeed, playing World Of Warcraft. (In fact, if you did the latter, you'd probably have more of an impact on the world.) People humour you, but nobody's interested in that any more than they are in what you had for lunch. I don't know whether this was always the case in the capital, or whether it was a result of Thatcherite/Blairite entrepreneurial values being adopted by the broader population, though it is a noticeable phenomenon.

2008/2/6

Following up from that piece on musical tastes in the UK, there's an article in the Graun speculating on how geography and history affect musical taste:

However, some music seems entrenched in certain areas, and while some believe this is due to the mystical forces exerted by ley lines, it is more likely attributable to a single act spawning an entire movement. "I think music is more determined by musical scenes that help create a distinctive sound," says academic and journalist Simon Frith, founder member of the International Association for the Study of Popular Music and chair of the Mercury music prize judging panel. "Glasgow has that history of guitar pop, and if you listen now to [Glasgow band] Glasvegas, it could be guitar pop of any age." Frith suggests that bands are inspired by the music that immediately precedes them - the music played perhaps by older siblings - and by the music that surrounds them, in local venues, on jukeboxes, radio stations. "The jangly guitars you hear in new Glasgow bands are the same jangly guitars you will hear played in Glasgow pubs," he says.

"I've looked at the fact that industrial Yorkshire and Lancashire are particularly strong areas for community-based music, such as brass bands, handbell ringing teams and choirs," he says. "They were all very powerful, particularly in smaller communities - it's partly to do with civic rivalries." Religion also played a big part, especially Methodism in Yorkshire. "Though John Wesley believed in the simplest form of music so as not to complicate the religious message, many of the local congregations took very enthusiastically to religious music, and so grew the choral tradition,"

In more recent times, Sheffield has shown itself to be home to music with a strong storytelling sense, with acts such as Pulp, the Arctic Monkeys and Richard Hawley. "The narrative thing I find interesting," says Frith, "because I always associated Sheffield with electronic music. It was the home of Warp and the Human League - though their songs did have a sense of narrative." Russell notes the strong love of amateur operatics in the area in the late 19th and early 20th century, "which created a love of humorous lyrics". Then, of course, came the music hall tradition. "And in some way the music hall spawned the very literate songwriting with wit and humour." It is precisely this we can see in the lyrics of Jarvis Cocker and Alex Turner.

But the Scottish love of American country and western is little more than a reclamation; country and western music was largely born of the music of the Appalachian Mountains, which itself was rooted in the music brought to American shores by immigrants from Europe, especially the British Isles. So country and western has much in common with traditional British folk music, Celtic music, and Scottish and Irish fiddle styles in particular. And those old habits die hard. "Apparently, karaoke caught on much quicker in Scotland and Ireland where they had the tradition of collective singing," adds Frith, "and where they had more of a tradition of the ballad."

2008/1/25

With it being Australia Day, The Age has a raft of articles looking at Australian culture and identity, including one examining the idea of something being "un-Australian" (for the first time since the end of the Howard era):

Current generations might believe that to be un-Australian and its attendant "ism" were coined in the conservative 1990s, when the values debate raged and the then prime minister, John Howard, spearheaded a failed attempt to get the term mateship enshrined in the constitution. But its ancestry goes back much further. Etymologically, it began life as a literal recognition of things that were not Australian in character; the first recorded use, in 1855, described a part of the landscape similar to Britain.

Cultural commentator Hugh Mackay has argued that anything labelled un-Australian is, in fact, Australian: "Surely it's 'Australian' to do whatever Australians do. It's Australian to drink and drive, to get hopelessly into debt, lie to secure an advantage — whether political, commercial or personal — and engage in merciless and slanderous gossip. It's Australian to give vent to our xenophobia through outbreaks of racism, to reserve our nastiest prejudices for indigenous people, and to worship celebrity … It's Australian to do such things because it's human to do them."And there's also a piece titled "I speak Aboriginal every day", about the surfeit of Aboriginal place names in Australia, most of their meanings all but forgotten to most of the people who use them:

Prahran turns out to be an Aboriginal word — a corruption of Birrarung (mist, or land surrounded by water). Dandenong was Tathenong (big mountain). Geelong comes from Tjalang (tongue). Moorabbin means "mother's milk". Looking up a single page in a street directory now to check a spelling (because I know these words better spoken than written), I find Kanooka, Kanowindra, Kanowna, Kantara, Kantiki, Kanu, Kanuka, Kanumbra, Kanyana … and on and on. Forty-five per cent of Victorian place names are Aboriginal.I didn't know that Prahran was an Aboriginal word; if pressed, I would have guessed that it was taken from India, perhaps in honour of some earlier triumph of the British Empire (by analogy to the area near Flemington which is sometimes referred to as Travancore), or alternately came, badly mangled, from some indigenous British minority language.

2008/1/15

Paul Torrens, of Arizona State University, has developed a computer model of crowd behaviour in cities, complete with graphics. The possibilities, as is pointed out here, are endless:

Such as the following: 1) simulate how a crowd flees from a burning car toward a single evacuation point; 2) test out how a pathogen might be transmitted through a mobile pedestrian over a short period of time; 3) see how the existing urban grid facilitate or does not facilitate mass evacuation prior to a hurricane landfall or in the event of dirty bomb detonation; 4) design a mall which can compel customers to shop to the point of bankruptcy, to walk obliviously for miles and miles and miles, endlessly to the point of physical exhaustion and even death; 5) identify, if possible, the tell-tale signs of a peaceful crowd about to metamorphosize into a hellish mob; 6) determine how various urban typologies, such as plazas, parks, major arterial streets and banlieues, can be reconfigured in situ into a neutralizing force when crowds do become riotous; and 7) conversely, figure out how one could, through spatial manipulation, inflame a crowd, even a very small one, to set in motion a series of events that culminates into a full scale Revolution or just your average everyday Southeast Asian coup d'état -- regime change through landscape architecture.

Or you quadruple the population of Chicago. How about 200 million? And into its historic Emerald Necklace system of parks, you drop an al-Qaeda sleeper cell, a pedophile, an Ebola patient, an illegal migrant worker, a swarm of zombies, and Paris Hilton. Then grab a cold one, sit back and watch the landscape descend into chaos. It'll be better than any megablockbuster movie you'll see this summer.And here are emotional maps of various urban areas, including parts of London and San Francisco, created by having volunteers walk around them with GPS units and galvanic skin response meters.

(via schneier, mind hacks) ¶ 0

2006/11/10

Jens Lekman writes about Gothenburg, specifically explaining the significance of Hammer Hill (which sounds like Sweden's answer to Bethnal Green or Notting Hill), Kortedala (which is apparently much, much worse) and Tram #7:

I told you where tram # 7 goes. It was a temporary stop. She don't live here anymore, it was a long time since we broke up. Still, taking # 7 from Sahlgrenska down to the Botanical Gardens is , if you do it at the right time, a breathtaking experience. The sky opens up, the tracks underneath creaking, the trees embracing you as you come down from the bridge and into the lushness of Slottskogen. I used to test my songs during this little trip. If they managed to keep me focused despite the heavenly views and the loud creaking, then they had something. The other day I took this trip and listened to the new songs. They did well.

2006/6/13

In Toronto, Canada, the local electric utilities have a tradition of disguising power substations as suburban houses, complete with balconies, windows and gardens. Known as "bungalow-style substations", the facilities have been built over many decades, in whatever style fit in best at the time, and according to a commenter, even hire someone to "live" in the houses on Halloween and hand out candy.

Meanwhile, in London, there is 23-24 Leinster Gardens, W2, where two terrace houses were demolished in 1867 to make what is now the District Line, and replaced with a convincing-looking and well kept-up façade.

When I lived at the end of Holden Street, North Fitzroy (map here), there was a house across the road which was condemned because it stood in the way of maintaining/replacing a water main that ran immediately beneath it. It had stood there for a year or two at least, slowly falling apart, no light emanating from its windows; at one point, a notice was attached to its front, detailing a plan to, after demolishing the house, build a façade across the front of the lot, in keeping with the neighbourhood's character. I don't know whether this has happened, or whether there is now a convincing pseudohouse in North Fitzroy; as of August 2004, the empty house was still standing, slowly, sadly falling apart.

(via Boing Boing) ¶ 1

2006/1/26

The Londonist reveals a list of places equivalent to Notting Hill around the world. (That's Notting Hill as in the part of West London, not as in the Working Title romcom.) These places include The Marais in Paris, Paddington in Sydney (though wouldn't Glebe be more Notting Hill?) and Christianshavn in Copenhagen; Manchester and Glasgow get two Notting Hill equivalents each: The Cliff and West Didsbury and Strathbungo and Garnethill respectively.

This research was carried out by the simple expedient of doing a Google search for "answer to notting hill". This technique can, of course, be extended to finding equivalents for other iconic districts: for example, Camden Town apparently has equivalents in Tokyo's Harajuku, San Francisco's Haight Ashbury (so that's full of brightly-coloured teenagers and mohician punks with "PUNK" in big letters on their clothing?), Stockholm's Hornstull and Buenos Aires' San Telmo. Running it for Melbourne locales was less fruitful; there are apparently no Brunswick Street equivalents anywhere, though there is one Chapel Street equivalent (Geelong's Packington Street).

Incidentally, there is no Melbourne equivalent of Notting Hill listed. Melbourne does have a locale named Notting Hill, but it is a rather desolate stretch of urban sprawl north of Monash University, where there are enough industrial estates to keep the student-infested 1970s bungalows spread out. Perhaps Carlton or Williamstown would be a more accurate equivalent?

2005/8/25

A beautiful and evocative piece of writing from Suw Charman about the subjective psychogeography of a city (in her case, London):

London is not a city. It's not a place. Not anymore. It's a mosaic of memories, as scattered through time as they are over the landscape. Five years of inhabitation followed by another five of constant visitation. Experience layered upon experience like thick coats of paint on old walls. Chip at it, pick at it, see what colour lies underneath.

Suddenly, a memory of the fish I saw on the pavement in Rotherhithe. There it was, a huge fish, still twitching, gasping, wanting water. It sat on the pavement in it's own little puddle of water in the middle of a hot summer's day, just yards from the Thames. There was no one in sight. When I come out of the corner shop, it's gone. Just a damp patch to show it was ever there. But still no one around.

I wonder if I'll remember that when I am old. I wonder how far into the future my past stretches. How much that is gone forever will be here forever? Where does my past end?

2004/9/29

Your Humble Narrator has recently arrived in North London, and has made the following observations:

- Holloway Road's closest Melbourne equivalent would be Sydney Rd., Brunswick. Grungy, downmarket, and running north-south through various working-class areas. (I think it's the street the record shop in High Fidelity is meant to be on, which basically is a way of saying that it'd be a small, obscure and struggling sort of place). There are no fashionable shops (except perhaps one near the Highbury end, which sells Ben Sherman gear rather cheaply), lots of bargain shops, discount phone-card vendors, internet cafés (the going rate seems to be £1/hour), halal fried chicken shops (the confluence of Islamic food-preparation doctrines and American-style fried chicken, often named after randomly-selected US states, is one of those puzzling artefacts of contemporary Britain, but I digress), and the odd McDonalds (though no Prets; that would be too posh). And most, but not all, of the shops have shutters (probably suggesting that the area used to be a no-go zone blacklisted by insurance companies, though has improved somewhat recently), usually covered with aerosol art. There are plenty of beggars, gnarled-looking trolls, working the streets; every cash machine seems to have an "attendant" sitting down beside it, ready to claim his perceived share of the privileged users' largesse.

- I've heard it claimed that Upper Street, Islington, is roughly equivalent to Chapel Street. Or possibly Brunswick Street, though probably not: Brunswick Street would probably be Camden High Street without the market; William Gibson called it the "Children's Crusade".

- North London seems like a rougher environment than inner Melbourne. There's a faint vibe of aggression in the streets, evident in groups of hard-looking youths. And then there are the local community newspapers: where the inner-Melbourne papers go on about insufficient community health-care funding and insensitive high-rise apartment developments, the papers here talk about gay-bashing youth gangs and muggings in broad daylight, and you know you're in a grittier, more hard-edged reality. Keep moving, don't make eye contact, and try not to look like a soft target.

- Highbury (which is east of Holloway Road) is a pleasant, village-like place; small shops and restaurants, leafy streets and a quiet atmosphere. The area around Highbury Grove/Blackstock Road (or A1201; given how often British roads' names change, most major ones are known by a number instead) and near Arsenal football stadium in particular seems rather pleasant.